Abandoning the Concept of Free Will

Song Bird

Knock knock

A computer simulation of a network of cosmic strin…

The Crisis of Print

From King to supplicant

This is you talking

Internet map 1024.jpg Wikipedia

LEVIATHAN

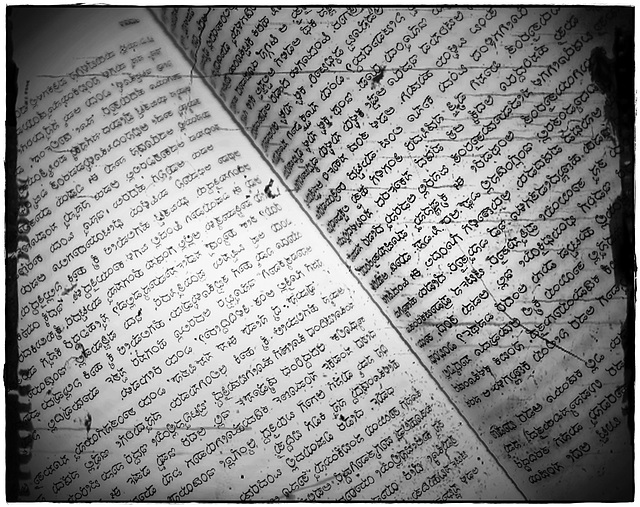

Fossil of Language

Cognitive study of Autumn colors

Memories

Thus spake Aristotle

Lesson from Locksmith

Keeping Memories

Language

Cipher as a Code & a Zero

Power of Mitrochondria

Algorithm

When is piece of matter said to be alive?

Squeegee Men

Social to the core

Mothers of Invention

The Elephant in the Boa Constrictor

Black Swan & David Hume!!

Fig.8-6. Apologies by political & religious leader…

Arthur Schopenhauer

J.Krishnamurthi & physicist David Bohm ~ 1984

Eratosthenes' Geodesy

"The Mystery of Consciousness"

Karl Marx

Thomas Hobbes 1588-1679

Arthur Schopenhauer

Words

Future of PC

Danate Alighieri

DASA

Giordani Bruno

Einstein

Bindu

Top: Islamic decoration - Badra Azerbaijan Bottom…

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

94 visits

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Even this primitive form of language could have been extremely useful to an early human society. Other possible echoes of the inferred proto-language can be heard in syntax-free utterance such as “Ouch!” or the more interesting “Shh!” which requires a listener.

Recently linguists have developed a new window into the innate basis of syntax through a remarkable discovery – the detection of two new languages in the act of coming to birth. Both are sign languages, developed spontaneously by deaf communities whose members were not taught the standard sing languages of their country. One is Nicaraguan Sign Language, invented by children in a Nicaraguan school for deaf. The other, Al-

Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, was developed by members of a large Bedouin clan who live in a village in the Negev desert of Israel.

According to a famous story in Herodotus’s “History”, an Egyptian king tried to ascertain the nature of the first language by isolating two children from birth and waiting to see in what tongue they first spoke. Study of the two new sign languages confirm that King Psammetichus’s experiment was misconceived: it is not specific words that are innate, but rather the system for generating syntax and vocabulary. …..

The apparently spontaneous emergence of word order and case ending in the two sing languages strongly suggests that the basic elements of syntax are innate and generated by genetically specified components of human brain. The Al-Sayyid sing language en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Sayyid_Bedouin_Sign_Language has been developed through only three generations but some signs have already become symbolic. The sign of man is a twirl of the finger to indicate curled mustache, even though the men of the village no longer wear them. ……

Sign languages emphasize an often overlooked aspect of language, that gesture is an integral accompaniment of the spoken word. The human proto-language doubtless included gestures, and could even have started with gestures alone. Michael Corballis, a psychologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, argues that language “developed first as a primarily gestural system, involving movements of the body, and more especially the hands, arms and face. Speech would have evolved only later, he believes, because considerable evolutionary change had to occur to develop the fine muscles of the tongue and other parts of vocal apparatus.

Once language started, whether in the form of word or gesture or both, its further evolution would doubtless have been rapid because of the great advantages that each improvement in this powerful faculty would have conferred on the possessors. Even while still in its most rudimentary form, language would have made possible a whole new level of social interactions……… Moreover each small improvement in the overall system, whether in precision of hearing or articulation of syntax formation, would confer further benefit, and the genes underlying the change would sweep through the population

Paleoanthropologists have tended to favor the idea that language started early, with Homo erectus or even the australopithecines, followed by slow and stately evolution. Archaeologists, on the other hand, tend to equate full-fledged modern language with art, which only becomes common in the archaeological record some 45,000 years ago. Their argument is that creation of art implies symbolic thinking in the mind of the artist, and therefore possession of language to share these abstract ideas.

If fully articulate modern language emerged only 50,000 years ago, just before modern humans broke out of Africa, then the proto-language suggested by Bickerton would have preceeded it. When might the proto-language first have appeared? If Homo ergaster possessed proto-language then so too would all its descendants, including the archaic hominids who reached the far East and Europe. But in the case the Neanderthals, to judge by their lack of modern behavior, appear never to have developed their proto language into fully modern articulated speech. That might seem surprising, given the advantage any improvement in the language faculty would confer on its owner, and the rapidity with which language might therefore be expected to evolve. So perhaps the Neanderthals didn’t speak at all.

A remarkable new line of inquiry bearing on the origins of language has recently been opened up by human genome project. This is the discovery of a gene that is intimately involved in many of the finer aspects of language. The gene, with the odd name FOXP2, shows telltale signs of having changed significantly in humans but not in chimps, exactly as would be expected for a gene serving some new faculty that had emerged only in the human lineage. And, though the ability of genetics to reach back into the distant past, the emergence of the new gene can be dated, though at present only very roughly.

But its evolution suddenly accelerated in the human lineage after the human and chimp lineages diverged. The human version of FOXP2 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FOXP2 protein differs in two units from that of chimps, suggesting that was subject to some strong selection pressure such as must have accompanied the evolution of language.

All humans have essentially the same version of FOXP2, the sign of a gene so important that it has swept through the population and become universal. By analyzing the variations in the FOXP2 genes possessed by people around the world, Pabbo was able to fix a date, tough rather roughly, for the time that all humans acquired the latest upgrade of FOXP2 gene. It was fairly recently in human evolution, and certainly sometime within the last 200,000 years, he concluded.

Societies with two kinds of people, of greatly differing language abilities, may have existed during the evolution of language. As each new variant gene arose, conferring some improvement in language ability, the carriers of the gene would leave more descendants. When the last of these genes – perhaps FOXP2 – swept through the ancestral human population, the modern faculty of language was attained

But in this first attempt to find a fascinating language I proceed blindly since I am guided only by the abstract and empty form of my object-state for the Other. I can not even conceive what effect my gestures and attitudes will have since they will always be taken up and founded by a freedom which will surpass them and since they can have a meaning only if this freedom confers one on them. Thus the “meaning’ of my expression always escapes me. I never know exactly if I signify what (I wish to signify nor even if I am signifying anything. It would be necessary that the precise instant I should read in the Other what on principle is inconceivable. For lack of knowing what I actually express for the Other, I constitute my language as an incomplete phenomenon of flight outside myself. As soon as I express myself, I can only guess at the meaning of I express -- i.e., the meaning of what I am -- since in this perspective to express and to be are one. The Other is always there, present and experienced as the one who gives to language its meaning. Each expression, each gesture, each word is on my side of concrete proof of the alienating reality of the Other. It is only the psychopath who can say, “someone has stolen my thought” -- as in cases of psychoses of influence, for example. The very fact of expression is a stealing of thought since thought needs the cooperation of an alienating freedom in other to be constituted as an object. That is why this first aspect of language -- in so far as it is I who employ it for the Other -- is ‘sacred.’ The sacred object is an object which is in the world and which points to a transcendence beyond the world. Language reveals to me the freedom (the transcendence) of the one who listens to me in silence. ~ Page 487

Excerpt "Being and Nothingness" Author - Jean-Paul Sartre

Sign-in to write a comment.