Arthur Schopenhauer

Words

Future of PC

Ouch! ... It's cold

Grass

Grass

Downtown

Chrysler

Ford

Chevrolet

Brush

.............? 1930

Ford Victoria 1951

Lincoln 1962

Chevy Impala 1958

Studebaker 1960

Ubiquitous

June 13th 2008

Gandhiji & his secretary Mahadev Desai

Karl Marx

"The Mystery of Consciousness"

Eratosthenes' Geodesy

J.Krishnamurthi & physicist David Bohm ~ 1984

Bring me the sunset in a cup

One evening

Twilight

Autumn Moon

"A Premier of the Daily Round"

One leaf on a branch

Walking alone In Dead of Winter

The Lane

January morning

Snowy woods

On ice

A Cardinal

No answer came

High places

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

221 visits

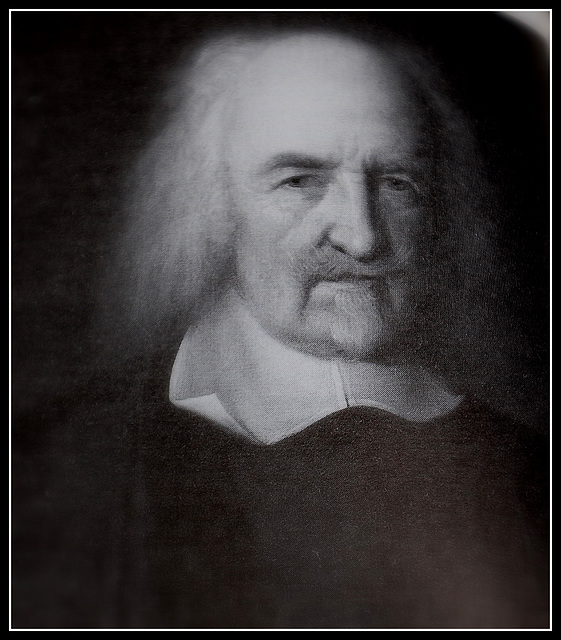

Thomas Hobbes 1588-1679

Hobbes grounds the citizens’ obligation to obey the law by on the promise of obedience. He explicitly says that a person ‘is obliged by his contracts, that is, that he ought to perform for his promise sake’. Third, Hobbes knew that the danger to the stability of the state did not arise from the self interest of all its ordinary citizens, but rather from the self interest of a few powerful persons who would exploit false moral views. He regarded it as one of the most important duties of the sovereign to combat these false views, and to put forward true views about morality, including is relationship to religion

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Like many thinkers of his day, Hobbes wasn’t just a philosopher - he was what we would now call a renaissance man. He had serious interests in geometry and science, and in ancient history too. As a young man he loved literature and had written and translated it. In philosophy, which he only took up in middle age, he was materialist, believing that humans were simply physical beings. There is no such thing s the soul: we are simply bodies, which are ultimately complex machines. ~ Page (A Little History of Philosophy by Nigel Warburton)

Hobbes (1588-1679) is a philosopher whom it is difficult to classify. He was am empiricist, like Locke, Berkeley, and Hume, but unlike them, he was an admirer of mathematical method, not only in pure mathematics, but in its applications. His general outlook was inspired by Galileo rather than Bacon. From Descartes to Kant, Continental philosophy derived much of its conception of the nature of human knowledge from mathematics, but it regarded mathematics as known independently of experience. It was thus led, like Platonism, to minimize the part played by perception, and over-emphasize the part played by pure thought….. . . . .His theory of the State deserves to be carefully considered, the more so as it is more modern than any previous theory, even that of Machiavelli. ~ Page 546

The political opinions expressed in the ‘Leviathan,’ www.gutenberg.org/files/3207/3207-h/3207-h.htm which were Royalist in the extreme, had been held by Hobbes for a long time. When the Parliament of 1628 drew up the Petition of Right, he published a translation of Thucydides, with the expressed intention of showing the evils of democracy. When the Long Parliament met in 1640, and Laud and Strafford were went to the Tower, Hobbes was terrified and fled to France. His book ‘De Cive’, www.public-library.uk/ebooks/27/57.pdf written in 1641, though not published till 1647, sets forth essentially the same theory as that of the ‘Leviathan.’ It was not the actual occurrence of the Civil war that caused his opinions, but the prospect of it, naturally, however, his conviction was strengthened when his fears were realized. ~ Page 547

We will now consider the doctrines of the ‘Leviathan,’ upon which the fame of Hobbes mainly rests.

He proclaims, at the very beginning of the book, his thorough-going materialism. Life, he says, is nothing but a motion of the limbs, and therefore automata have an artificial life. The commonwealth which he calls ‘Leviathan,’ (the word Leviathan ~ { (in biblical use) a sea monster, identified in different passages with the whale and the crocodile (e.g. Job 41, Ps. 74:14), and with the Devil (after Isa. 27:1).} as more than an analogy, and is worked out in some detail. The sovereignty is an artificial soul. The pacts and covenants by which ‘Leviathan’ is first created take the place of God’s fiat when He said “Let Us make man.”

The first part deals with man as an individual, and with such general philosophy as Hobbes deems necessary. Sensations are caused by the pressure of objects; colours, sounds, etc., are not in the objects. The qualities in objects that correspond to our sensations are motions. The first law of motion is stated, and is immediately applied to psychology: imagination is a decaying sense, both being motions. Imagination when asleep is dreaming; the religions of the gentiles came of not distinguishing dreams from waking life. (The rash reader may apply the same argument to the Christian religion, but Hobbes is much too cautious to do so himself) (Elsewhere he says that the heathen gods were created by human fear, but that our God is the First Mover.) Belief that dreams are prophetic is a delusion; so is the belief in witchcraft and in ghosts.

The succession of our thoughts is not arbitrary, but governed by laws -- sometimes those of association, sometimes those depending upon a purpose in our thinking.

Hobbes, as might be expected, is an out-and-out nominalist. There is, he says, nothing universal but names, and without words we could not convince any general ideas. Without language, there would be no truth or falsehood, for “true” and “false” are attributes to speech. ~ Page 548/549

‘Will’ is nothing but the last appetite or aversion remaining in deliberation. That is to say, will is not something different from desire and aversion, but merely the strongest in a case of conflict. This is connected, obviously, with Hobbes denial of free will.

Unlike most defenders of despotic governments Hobbes holds that all men are naturally equal. In a state of nature, before there is any government, every man desires to preserve his own liberty, but to acquire dominion over others; both these desires are dictated by the impulse to self-preservation. From their conflict arises a war of all against all, which makes life “nasty, brutish, and short.” In a state of nature, there is no property, no justice or injustice; there is only war, and “force and fraud are, in war, the two cardinal virtues. ~ Page 550

It is admitted that the sovereign may be a despotic, but even the worst despotism is better than anarchy. Moreover, in many points the interests of the sovereign are identical with those of his subjects. He is richer if they are richer, safer if they are law-abiding, and so on. Rebellion is wrong, both because it usually fails, and because, if it succeeds, it sets a bad example, and reaches others to rebel. The Aristotelian distinction between tyranny and monarchy is rejected; a “tyranny,” according to Hobbes, is merely a monarchy that the speaker happens to dislike. - Page 552

Throughout the ‘Leviathan,’ Hobbes never considers the possible effect of periodical elections in curbing the tendency of assemblies to sacrifice the public interest to the private interest of their members. He seems in fact, to be thinking, not of democratically elected Parliaments, but of bodies like the Grand Council in Venice or the House of Lords in England. He conceives democracy, in the manner of antiquity, as involving the direct participation of every citizen in legislation and administration; at least, this seems to be his view. ~ Page 554

Excerpt: "The History of Western Philosophy" ~ Bertrand Russell

Sign-in to write a comment.