The Crisis of Print

From King to supplicant

This is you talking

Internet map 1024.jpg Wikipedia

LEVIATHAN

Fossil of Language

Cognitive study of Autumn colors

Memories

Thus spake Aristotle

Lesson from Locksmith

Keeping Memories

Language

Cipher as a Code & a Zero

Power of Mitrochondria

Algorithm

The Human Condition

Evolution/consequences

Aristotle

Money/Geld/dinheiro/ 貨幣/ பணம்/ деньги/ অর্থ/ เงินต…

Samskrata ~ Sanskrit ~ संस्कृतम्

What goes with it A or B

Knock knock

Song Bird

Abandoning the Concept of Free Will

Language

When is piece of matter said to be alive?

Squeegee Men

Social to the core

Mothers of Invention

The Elephant in the Boa Constrictor

Black Swan & David Hume!!

Fig.8-6. Apologies by political & religious leader…

Arthur Schopenhauer

J.Krishnamurthi & physicist David Bohm ~ 1984

Eratosthenes' Geodesy

"The Mystery of Consciousness"

Karl Marx

Thomas Hobbes 1588-1679

Arthur Schopenhauer

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

121 visits

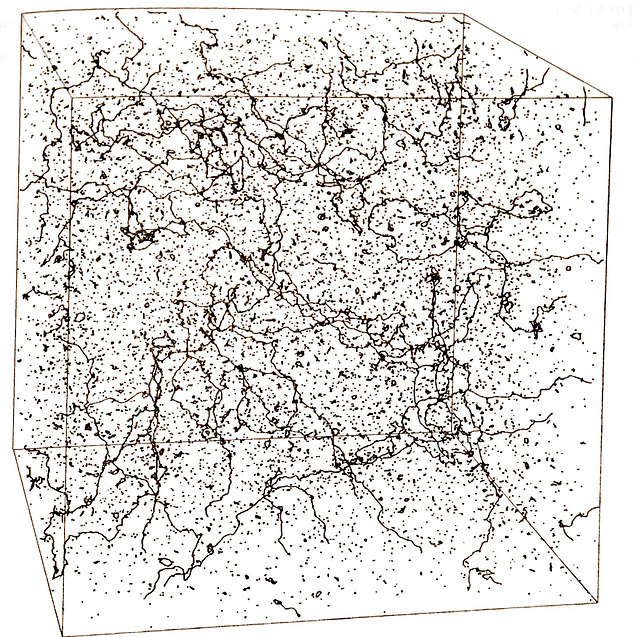

A computer simulation of a network of cosmic strings in an expanding universe, provided by Paul Shellard

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

The only novel contribution to this problem before twentieth century was the consideration of whether the well defined concept of mathematical existence had any cosmological implications. The development of axiomatic mathematical systems, in which a system of self consistent rules (‘axioms’) were laid down and consequences deduced or constructed from them, led to a ‘creation’ of mathematical statement that was logically consistent was said to ‘exist’. Mathematicians would produce what became known as ‘existence proofs’. This is clearly a far broader concept of existence than physical existence. Not all the things that are logically possible seem to be physically possible and not all of those now seem physically to exist. However, a philosopher like Henri Bergson clearly thought that this type of weak mathematical existence was a possible avenue along which to search for a satisfying solution to Leibniz’s problem:

“I want to know why the universe exists… Whence comes it, and how can it be understood, that anything exists? … Now, if I push these questions aside and go straight to what hides behind them, this is what I find: - Existence appears to me like a conquest over nought… If I ask myself my bodies or minds exist rather than nothing, I find no answer; but that a logical principle, such as A = A, should have the power of creating itself, triumphing over the nought throughout eternity, seems to be natural … Suppose, then, that the principle on which all things rest, and which all things manifest, possess an existence of the same nature as that of the definition of the circle, or as that of the axiom A = A: the mystery of existence vanishes…..”

Unfortunately, this approach to why we see what we see is doomed to failure. As the nature of axiomatic systems has become more fully appreciated it is clear that any statement can be ‘true’ in the same mathematical system. Indeed, a statement which is true in one system might be false in another. ~ Page 284 (The Book of nothing)

Sign-in to write a comment.