Humming bird

Brother of Summer

*

Lombardi's

Lombardis

Subway Art

At Chalsea Market

Willy Nelson

At Chelsea Market

A Street scene

Times SQ

Door

Men in Black (Supporting Actors)

Tube

Fire / Police

Manhattan

Chalsea Market

Chalsea Market

Times SQ

Manhattan skyline

Little Italy

Manhattan skyline

Street scene

Ms.Liberty

Freedom Tower ~ June 11th, 2011

Freedom Tower - June 11, 2011

Bull market

Roots

Wall Street

Italian Ices are back

Door

Spring Street

Blue Jay

Art

Nostalgia in the making

Tamesgen

Home

Lost

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

- Photo replaced on 24 May 2020

-

111 visits

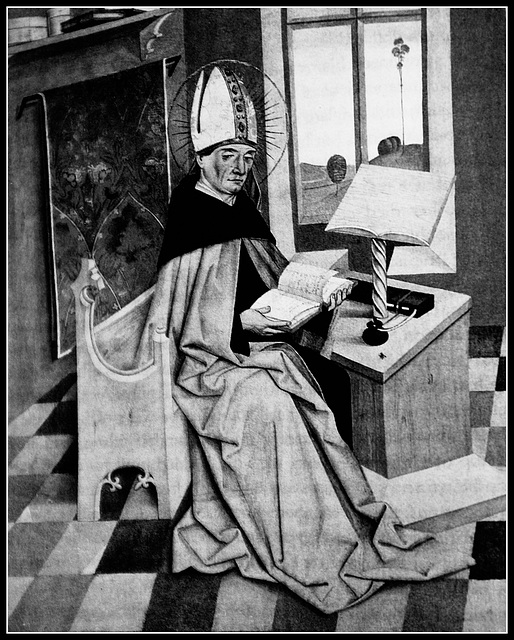

Augustine

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Not until the twentieth century did philosophers again take such a sensitive interest in the acquisition of language by infants. ~ Page 115-116

In the eleventh book of the ‘Confessions’ Augustine makes his celebrated inquiry into the nature of time. The peg on which the discussion hangs is the question of an objector: what was God doing before the world began? Rejecting the answer ‘Preparing hell for people who ask inquisitive questions’, Augustine responds that before heaven and earth were created, there was no time. We cannot ask what God was doing then, because there was ‘then’ when there was no time. Equally, we cannot ask why the world was not created sooner, for before the world, there was no sooner. It is misleading to say even of God that he existed at a time earlier than the world’s creation, for there is no succession in God. In him today does not replace yesterday, nor give way to tomorrow, there is only an eternal present.

In order to defend his account of eternity, Augustine has to argue that time is unreal. “What is time?’ he asks, ‘If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain to one that asks, I know not.’ Time consists of past, present, and future. But only the present exists, for the past is no longer, and the future is not yet. But a present that is only present is not time, but eternity.

We speak of longer and shorter times; but how can we measure time? Suppose we say of the past period that it was long: do you mean that it was long when it was past, or long when it was present? Only the latter makes sense; but how can anything be long in the present, since what a present is instantaneous? No collections of instants can add up to more than an instant. The stages of any period of time never co-exist; how then can they be added up to form a whole? Any measurement we make must be made in the present: how can we measure what has already gone or is not yet there?

Augustine’s solution to these perplexities is to say that time is really only in the mind. The past is not, but I behold it in the present because it is, at this moment, in my memory. The future is not; all that there is, is our present foreseeing. Instead of saying that there are three times, past, present and future, we should say that there is a present of things past (which is memory), a present of things present (which is sight), and a present of things future (which is expectation). A length of time is not really a length of time, but a length of memory, or a length of expectation. ~ page 117

Throughout the Catholic Middle Ages, Augustine enjoyed grater authority than any of the other Church Fathers, and at the Reformation his influence increased rather than diminished. John Calvin sharpened and hardened Augustine’s teachings just as Augustine had sharpened and hardened that of Paul. Even at the present time, when many more people hate him than read him, Augustine’s influence on Christian thought is inescapable, and his genius continues to fascinate or repel many outside the Christian tradition. ~ page 120

Augustine undertook this sweeping exposition in the number of ways. He provided, the example, a theory of history that accounted for human events in terms of providential logic, showing how

God’s hand was forever at work in the world, frustrating the pretentions of empires and individuals to independence. Rome had grown mighty not through its own initiative but because it served God’s plan. And now God was realizing his larger purpose through Rome’s fall, hastening time toward its final end in the duty of judgment. When that day would come, Augustine emphasized (like others before), no one could know, and his insistence on the point helped put an end to formal millennial speculation within the church. Still, one could be sure that behind the apparent chaos of human events lay a divine logic, not always discernible to the naked eye but giving order and meaning to the whole nonetheless. ~ Page 101/102 Excerpt” : “Happiness ~ A history” Author Darrin M. Mc Mohan

The finest representative of blending of classical and Christian ideas, and indeed one of the most brilliant thinkers in the history of the Western world, was Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430) www.augustinian.org/saint-augustine plato.stanford.edu/entries/augustine Aside from the scriptural writers, no one else has had a greater impact on Christian thought in succeeding centuries. . . . . .

At the age of seventeen, Augustine went to nearby Carthage to continue his education. There he took a mistress with whom he lived for fifteen years. At Carthage, Augustine entered a difficutly psychological phase and began an intellectual and spiritual pilgrimage that led him through experiments with several philosophies and heretical Christian sects. In 383 he traveled to Rome, where he endured illness and disappointed his teaching: his students fled when their bills were due.

Augustine’s autobiography, ‘The Confessions,’ is a literary masterpiece and one of the most influential books in the history of Europe. Written in the form of a prayer, its language is often incredibly beautiful. www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3296/pg3296.txt

‘The Confessions’ described Augustine’s moral struggle, the conflict between his spiritual and intellectual aspirations and his sensual and material self. ‘The Concessions’ reveals the change and development of human mind and personality steeped in the philosophy and culture of the ancient world.

Many Greek and Roman philosophers had taught that knowledge and virtue are the same: a person who really knows what is right will do what is right. Augustine rejected this idea. He believed that a person may know what is right but fail to act righteously because of the innate weakness of the human will. People do not always act on the basis of rational knowledge. Here Augustine made a profound contribution to the understanding of human nature: he demonstrated that a learned person can also be corrupt and evil. ‘The Confessions,’ wirtten in the rhetorical style and language of late Roman antiquity, marks the synthesis of Greco-Roman forms and Christian thought. ~ page 207

Sign-in to write a comment.