LEVIATHAN

Fossil of Language

Cognitive study of Autumn colors

Memories

Thus spake Aristotle

Lesson from Locksmith

Keeping Memories

Language

Cipher as a Code & a Zero

Power of Mitrochondria

Algorithm

The Human Condition

Evolution/consequences

Aristotle

Money/Geld/dinheiro/ 貨幣/ பணம்/ деньги/ অর্থ/ เงินต…

Samskrata ~ Sanskrit ~ संस्कृतम्

What goes with it A or B

Manchester

Identifying the Political Spectrum

Tree in its essential form

Mind ~ Latin: mens, Sanskrit: manas, Greek: μένος

This is you talking

From King to supplicant

The Crisis of Print

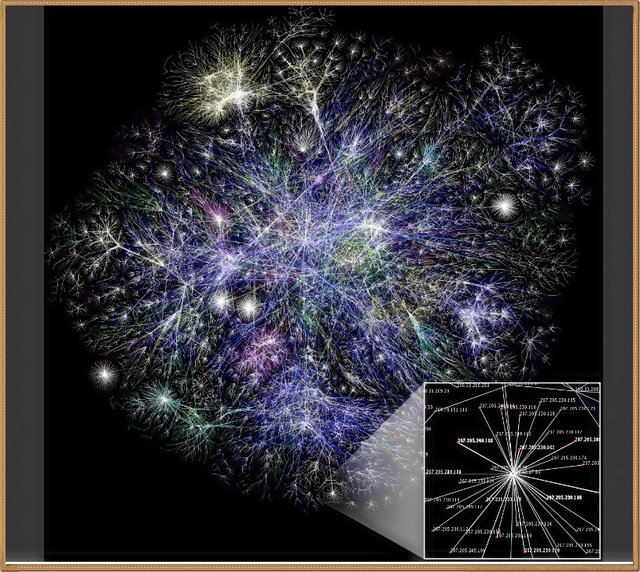

A computer simulation of a network of cosmic strin…

Knock knock

Song Bird

Abandoning the Concept of Free Will

Language

When is piece of matter said to be alive?

Squeegee Men

Social to the core

Mothers of Invention

The Elephant in the Boa Constrictor

Black Swan & David Hume!!

Fig.8-6. Apologies by political & religious leader…

Arthur Schopenhauer

J.Krishnamurthi & physicist David Bohm ~ 1984

Eratosthenes' Geodesy

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

197 visits

Internet map 1024.jpg Wikipedia

In a 2005 speech, the CEO of Google, Eric Schmidt, for the first time offered an estimate of the size of the Internet in total bytes of memory.

He put the total at 5 million trillion bytes – or, based on the average size of the computer byte – about 50,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (50 sex-trillion) bites. All of this memory, representing a sizeable portion of all human knowledge and memory, was stored virtually in more than 150 million websites, and physically in an estimated 75 million services located around the world. None of these numbers were accurate, other researchers added, and some might of off in either direction by a factor of five.

Of this total size of the Internet, Schmidt estimated that Google, by far the world’s leading search-engine company, had managed after seven years to index 200 trillion bytes (terabytes), or just .004 percent of the Net. Most of the rest, he admitted, was essentially terra incognita – a vast region of unexplored data that might never be fully known. At the current rate, Google would need 300 years to index the entire Internet – and that, Schmidt added, was only assuming the impossible: that the Net probably grew by several trillion bytes just during the course of Schmidt’s speech.

By 2010, these unimaginable contents of the Net were accessed by just short of 1 billion personal computers, nearly 700 million smart-phones (the total for 2011), and several hundred million other devices large and small, in the hands of estimated 2 billion users worldwide. Some of these users, mostly from the developed world, arrived in cyber-pace using powerful computers and handheld devices, linked via wire-less networks or broadband cable, and stored hundreds of gigabytes of memory of their own.

Others, newer to the Web and often from developing nations, had reached the Internet any way they could: dial-up modems, cell phones rented from corner stands, desktop computers stationed in classrooms and local libraries, Internet cafes of the kind long gone from the West. But they’d make it at last, and whether they were selling goods on eBay or following bloggers covering events their censored national media wouldn’t touch or taking online classes at distant universities they would never see, they were the first generation to have access to the world’s accumulated memory. And because of that, they inhabited a unique new reality that name of their ancestors had ever experienced. For the first time, these billions (and 2 billion more are expected to join this global conversation within the next decade) had access to almost everything every human has ever known. And it was at their fingertips. And it was as good as free. ~ Page 238/239

He put the total at 5 million trillion bytes – or, based on the average size of the computer byte – about 50,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (50 sex-trillion) bites. All of this memory, representing a sizeable portion of all human knowledge and memory, was stored virtually in more than 150 million websites, and physically in an estimated 75 million services located around the world. None of these numbers were accurate, other researchers added, and some might of off in either direction by a factor of five.

Of this total size of the Internet, Schmidt estimated that Google, by far the world’s leading search-engine company, had managed after seven years to index 200 trillion bytes (terabytes), or just .004 percent of the Net. Most of the rest, he admitted, was essentially terra incognita – a vast region of unexplored data that might never be fully known. At the current rate, Google would need 300 years to index the entire Internet – and that, Schmidt added, was only assuming the impossible: that the Net probably grew by several trillion bytes just during the course of Schmidt’s speech.

By 2010, these unimaginable contents of the Net were accessed by just short of 1 billion personal computers, nearly 700 million smart-phones (the total for 2011), and several hundred million other devices large and small, in the hands of estimated 2 billion users worldwide. Some of these users, mostly from the developed world, arrived in cyber-pace using powerful computers and handheld devices, linked via wire-less networks or broadband cable, and stored hundreds of gigabytes of memory of their own.

Others, newer to the Web and often from developing nations, had reached the Internet any way they could: dial-up modems, cell phones rented from corner stands, desktop computers stationed in classrooms and local libraries, Internet cafes of the kind long gone from the West. But they’d make it at last, and whether they were selling goods on eBay or following bloggers covering events their censored national media wouldn’t touch or taking online classes at distant universities they would never see, they were the first generation to have access to the world’s accumulated memory. And because of that, they inhabited a unique new reality that name of their ancestors had ever experienced. For the first time, these billions (and 2 billion more are expected to join this global conversation within the next decade) had access to almost everything every human has ever known. And it was at their fingertips. And it was as good as free. ~ Page 238/239

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

He put the total at 5 million trillion bytes – or, based on the average size of the computer byte – about 50,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (50 sex-trillion) bites. All of this memory, representing a sizeable portion of all human knowledge and memory, was stored virtually in more than 150 million websites, and physically in an estimated 75 million services located around the world. None of these numbers were accurate, other researchers added, and some might of off in either direction by a factor of five.

Of this total size of the Internet, Schmidt estimated that Google, by far the world’s leading search-engine company, had managed after seven years to index 200 trillion bytes (terabytes), or just .004 percent of the Net. Most of the rest, he admitted, was essentially terra incognita – a vast region of unexplored data that might never be fully known. At the current rate, Google would need 300 years to index the entire Internet – and that, Schmidt added, was only assuming the impossible: that the Net probably grew by several trillion bytes just during the course of Schmidt’s speech.

By 2010, these unimaginable contents of the Net were accessed by just short of 1 billion personal computers, nearly 700 million smart-phones (the total for 2011), and several hundred million other devices large and small, in the hands of estimated 2 billion users worldwide. Some of these users, mostly from the developed world, arrived in cyber-pace using powerful computers and handheld devices, linked via wire-less networks or broadband cable, and stored hundreds of gigabytes of memory of their own.

Others, newer to the Web and often from developing nations, had reached the Internet any way they could: dial-up modems, cell phones rented from corner stands, desktop computers stationed in classrooms and local libraries, Internet cafes of the kind long gone from the West. But they’d make it at last, and whether they were selling goods on eBay or following bloggers covering events their censored national media wouldn’t touch or taking online classes at distant universities they would never see, they were the first generation to have access to the world’s accumulated memory. And because of that, they inhabited a unique new reality that name of their ancestors had ever experienced. For the first time, these billions (and 2 billion more are expected to join this global conversation within the next decade) had access to almost everything every human has ever known. And it was at their fingertips. And it was as good as free. ~ Page 238/239

Sign-in to write a comment.