Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey

Riddle

Dance of Shiva

An exhibit

Barn

Just Now

One Art

The Wheel

Alone

Michigan State University

On a Spring bough

Czech Bakery

Fall Morning

Diagram ~ Voyager Spacecraft Golden Record

Meadow

Winter Trail

Yes

Happiness is when

At Boston MA

Winter

Hilflos

Downtown ~ Winter Day

Dark Days of Autumn Rain

Colours of Nature

Memories

End of a day

Kick at the rock, Sam Johnson, break your bones: B…

Peripatetikos / Walking

Bath Tissue

Napkins

Kurt Godel's equation

Fuegia Basket

Speed

Only Words

I'm not a person

Backyard Winter

Winter Sunlight and shadow

Winter Evening

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

28 visits

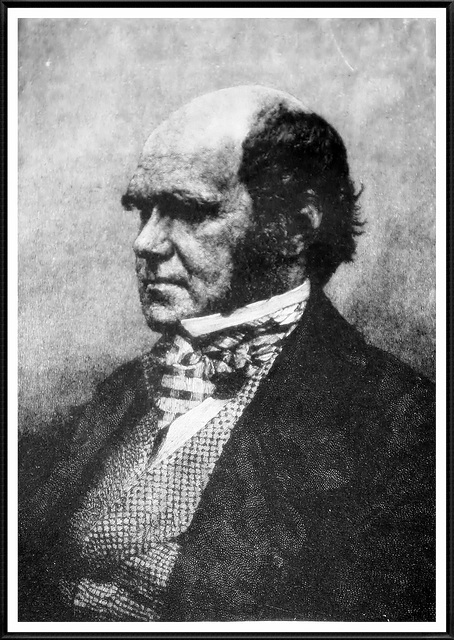

Darwin

darwin-online.org.uk/manuscripts.html

If I were to give an award for the single best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else. In a single stroke, the idea of evolution by natural selection unifies the realm of life, meaning, and purpose with the realm of space and time, cause and effect, mechanism and physical law. But it is not just a wonderful scientific idea. It is a dangerous idea. My admiration for Darwin’s magnificent idea is unbounded, but I, too, cherish many of the ideas and ideals that it seems to challenge, and want to protect them. ~ Page 21 (Daniel Dennett) Excerpt: Darwin's Dangerous Idea

If I were to give an award for the single best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else. In a single stroke, the idea of evolution by natural selection unifies the realm of life, meaning, and purpose with the realm of space and time, cause and effect, mechanism and physical law. But it is not just a wonderful scientific idea. It is a dangerous idea. My admiration for Darwin’s magnificent idea is unbounded, but I, too, cherish many of the ideas and ideals that it seems to challenge, and want to protect them. ~ Page 21 (Daniel Dennett) Excerpt: Darwin's Dangerous Idea

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

A modicum of material comforts, an absence of pain, a clear conscience, and a taste for the pleasures of the intellect -- this is the happiness of the “philosopher,” the “wise man,” to which state Darwin himself of the almost certainly aspired. The same general goal would not have been foreign to Aristotle, Epicurus, or Horace, or to any number of other thinkers we have encountered thus far. Indeed, the many reference in Darwin’s notes to Coleridge, Montaigne, Locke, Bentham, Adam Smith, Kant, and Mill give ample evidence of his prodigious reading and desire to situate his thinking about happiness in the context of a much broader tradition. There are “two classes of moralists,” he writes in a different notebook from the same period: theorists of the moral sense, on the one hand, and those, like Bentham and Mill, on the other, who tend to derive moral phenomena from acquired experience (the calculus of pleasure and pain). “One says we have a moral sense. -- But my view [says] unites both [and shows them to be almost identical]

Here, after having so far largely restated the views of others, Darwin hints as genuinely originality. Speaking of an “instinctive” moral sense, he observes, “In judging of . . . the rule of happiness we must look ‘far forward’ . . . -- certainly because it is the result of what has generally been best for our good far back.” Enticingly, he then adds, “Society could not go on except for the moral sense, any more than a hive of Bees without their instincts.” Darwin is positing not only what he called “instinctive emotions” -- emotions conditioned by heredity and the long experience of pleasure and pain -- but also a finely developed moral instinct, similarly hones by long experience. Both bear directly on our social interactions, and both are bound up closely with happiness.

Looking to the remote past, Darwin speculates that certain strong passions and “bad feelings” that are “common to other animals and therefore to [our] progenitor[s] far back were “no doubt originally necessary.” Revenge, for instance, once served as a primitive form of justice, anger secured our safety, and jealousy acted as a “positive check” on licentiousness. But though it was not odd that man should have developed such strong emotions in the first place (“with lesser intellect” Darwin adds, “they might be necessary and no doubt were preservative”) experience has shown that we now need to “check” these instincts in the service of happiness. In a striking formulation, Darwin observes, “Our descent, then, is the origin of our evil passions!! -- The Devil under from the Baboon is our grandfather! -- “ In a very real way, it seems, human beings must struggle with the beast within. ~ Page 413

. . . .In an extended passage treating what Darwin called the “general delusion about free will,” he observed that human beings’ belief in their own moral agency stemmed largely from their inability to discern the true motives of their behavior. “Originally most INSTINCTIVE, and therefore now [requiring a] great effort of reason to discover them” -- seemed loathe to confront what the evidence he was amassing might also suggest: that far from being free to alter our behavior for greater happiness and the greatest good, human beings might be captive to the hidden motives that ruled them, slaves to the beast within. ~ Page 414

The feeling of pleasure from society is probably an extension of the parental or filial affections, since the social instinct seems to be developed by the young remaining for a long time with their parents; and this extension may be attributed in part to habit, but chiefly to Natural Selection with those animals which were benefited by living in close association, the individuals which took the greatest pleasure in society would best escape various dangers, whilst those that cared least for their comrades, and lived solitary, would perish in greater numbers. ~Page 417

Darwin had little doubt that if human beings were raised like bees in a hive, they would act similarly, pointing out that in the case of infanticide, they already did. But his larger point was more optimistic. For in the social instinct of animals, Darwin found the precursor of the moral instinct of man. The one, he believed, was just an extension of the other, an impulse honed by natural selection and higher human consciousness to sympathy, affection, regard for one’s image in the eyes of others, and concern their welfare. Darwin fully recognized that this moral instinct would frequently come in confloict with other, more selfish desires. It is “untenable,” he stressed, “that in man the social instinct (including the love of praise and fear of blame) possess greater strength, or have, through long habit, acquired greater strength than the instincts of self-preservation, hunger, lust, vengeance, &c.” though envy, hatred and other passions of self-preservation would “more commonly lead [man] to gratify his own desires at the expense of other men, “it was also precisely this conflict between competing natural impulses that gave rise to conscience. As Darwin had intimated in his 1838 notes, and now repeated here, by virtue of his superior mental faculties, man “cannot avoid reflection: past impressions and images are incessantly and clearly passing through his mind.” And so, after indulging a stronger selfish impulse at the expense of his social instinct, man “will then feel remorse, repentance, regret, or shame. .. He will consequently resolve more or less firmly to act differently for the future, and this is conscience; for conscience looks backwards, and serves as a guide for the future. ~ Page 418

In looking toward the future on this occasion, Darwin gave indications of the same optimistic tendency recorded in his private reflections of the 1830s. At times he waxes sanguine, nothing, “Man prompted by his conscience, will through long habit acquire such perfect self-command, that his desire and passions will at last yield instantly and without a struggle to his social sympathies and instincts…..” in another passage he invokes Kant in a triumphant vision of man as a self-legislating moral actor:

”But as love, sympathy and self-command become strengthened by habit,k and as the power of reasoning becomes clearer, so that man can value justly the judgments of his fellows, he will feel himself impelled, apart from any transitory pleasure or pain, to certain lines of conduct. He might then declare -- not that any barbarian or uncultivated man could thus think -- I am the supreme judge of my conduct, and in the words of Kant, I will not in my own person violate the dignity of humanity”

This is an appealing picture of human independence and moral agency. But what of Darwin’s earlier concerns about the “general delusion of free will”? More pressingly, what about the place of happiness in his revised picture of humanity? Kant, it will be recalled, and emphasized the tension between a life of moral duty and individual happiness. The two, he believed, would often at odds. Darwin also is aware of this tension -- between, in his terms, the social instinct and individual desire though he makes reference “to that feeling of dissatisfaction, or even misery, which invariably results . . . from any unsatisfied instinct,” he does not explore this insight in any significant detail. . . . Page 419

Sign-in to write a comment.