She Rose

HE·ROES,

1) A person, typically a man, who is admired for courage or noble qualities.

2) A person who, in the opinion of others, has heroic qualities or has performed a heroic act and is regarded as a model or ideal.

Eliza Suggs: Shadow and Sunshine

| |

|

Sunshine and Shadow was published in 1906. It's the memoir of an African American young woman born enslaved and with a disability never able to walk or fully care for herself. She had strong religious convictions and often preached in black churches while held in the arms of her sister.

Her parents were enslaved, and Suggs' memoir contains accounts of their lives, as well as other sketches of enslaved life, Eliza's account of her own life, and several of her poems and hymns. A seminar on her life was held at the University of Nebraska in 1901.

The following is an excerpt of the Introduction from her book: While attending a camp meeting near Alma, Nebraska, during the summer of 1895, my attention was drawn to a little colored girl sitting in a baby cab, who appeared to take a deep interest in the services. I was told that it was Sister Eliza Suggs, who, amid deep affliction, was developing into a strong Christian character.

While the reader will be touched by the scenes of suffering related in this narrative, he will be impressed that Eliza does not belong to the despondent class. She is evidently of a cheerful temperament, possessing an overcoming faith which gives her the assurance that the God whom she loves and serves, intends to provide for and sustain her until life's journey is ended.

She saw light where others would have seen only darkness; she cherished hope where others would have felt only despair; and fearing it might displease her Master, she rejected offers of worldly gain which others would have eagerly grasped. Of humble parentage, limited advantages, physical embarassments, she is shedding rays of light along her pathway, and making impressions for good on the hearts and lives of those with whom she associates. What a marvel of grace!

Eliza Suggs (b.1876) died on January 29, 1908 in Orleans, Nebraska. She is buried with her family in Orleans Cemetery in Harlan County, Nebraska.

Sources: Documenting the American South; photo comes from Eliza's book Shadow and Sunshine

Anna Louise James

| |

|

Anna Louise James stands behind the soda fountain in the James' pharmacy.

She was born on January 19, 1886, in Hartford, Connecticut. The daughter of a Virginia plantation slave who escaped to Connecticut, she grew up in Old Saybrook. Dedicating her early life to education, Anna became, in 1908, the first African American woman to graduate from the Brooklyn College of Pharmacy in New York. She operated a drugstore in Hartford until 1911, when she went to work for her brother-in-law at his pharmacy, making her the first female African American pharmacist in the state.

The pharmacy where James worked started out as a general store for the Humphrey Pratt Tavern in 1790. The store moved to its current location at the corner of Pennywise Lane in 1877, where it became Lane Pharmacy. Peter Lane, one of only two black pharmacists in early Connecticut, added a soda fountain to his establishment in 1896.

When Peter got called away to fight in World War I, he left the pharmacy in the care of his sister-in-law, Anna Louise James. In 1917, Anna took over the operations and renamed her business James Pharmacy. Anna, known to local residents as “Miss James,” operated the business until 1967.

After her retirement, Anna Louise James kept residence in an apartment in the back of the pharmacy until her death in 1977.

The store itself remained vacant from 1967 until 1980, when it was renovated and reopened in 1984. Although the building has changed owners numerous times over the years, the former pharmacy, now primarily an ice cream shop, retains much of the character James instilled in it.

In 1994, the James Pharmacy received a listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Source: Historical Society of Connecticut/Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Lutie A Lytle: First African American to be admitt…

| |

|

In October 1897 Topekans were buzzing with the news that one of their own was a pioneer in her field. One of only two students in Central Tennessee law school's graduating class of 1897, Lutie A. Lytle was among the first African American woman to earn a law degree.

Lytle was born around 1875 in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where her father's family had lived for some time. John R., Mary Ann "Mollie", the family's four children and Lutie's grandmother moved to Kansas around 1882, a time when many other African Americans were relocating from Tennessee to Kansas with the Exoduster movement.

The Lytle family lived at 1435 Monroe Street and Lutie and her brothers attended Topeka schools, including Topeka High School. John became active in the Populist Party and ran an unsuccessful campaign for city jailor. His involvement led to Lutie's appointment as the Populist's assistant enrolling clerk for the state legislature. She also worked for one of the African American newspapers in Topeka. It was in this position where she dreamt of higher pursuits.

"I conceived the idea of studying law in a printing office where I worked for years as a compositor," Lutie said during an interview 1897. "I read the newspaper exchanges a great deal and became impressed with the knowledge of the fact that my own people especially were the victims of legal ignorance. I resolved to fathom its depths and penetrate its mysteries and intricacies in hopes of being a benefit to my people."

At the age of 21, Lutie moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee. There she taught school to pay for her tuition at Central Tennessee College in Nashville. While in college, Lutie also became involved other social activities.

"There were a number of young men studying beside her, but she held her own with them all," stated a Nashville newspaper in 1897. "Though she studied hard, she did not shut herself out from the enjoyment of the society of her fellow students. She was a member of the college glee club, and at the numerous musical entertainments given by the students she was invariably relied upon to accompany on the piano."

In September 1897 Lytle was admitted to the Criminal Court in Memphis, Tennessee, after passing an oral exam. Newspaper accounts said that she was the first African American woman to be licensed to practice in Tennessee, and third in the United States. Later that month, after returning to Topeka, she became the first African American woman admitted to the Kansas bar.

Lutie continued to dream of helping other African Americans through the legal system, as she talked of establishing a practice in Chicago or New York. "I like constitutional law because the anchor of my race is grounded on the constitution," Lytle said. "It is the certificate of our liberty and our equality before the law. Our citizenship is based on it, and hence I love it."

"In connection with my law practice I intend to give occasional lectures, but not in any sense for personal benefit," Lytle said. "I shall talk to my own people and make a sincere and earnest effort to improve their condition as citizens. I believe in efficacy of reason to bring about the best results."

For the next year, Lutie lived in Topeka and became involved in the Interstate Literary Association with members from Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas communities. She was invited to lecture for women's groups and local colleges on law related to domestic issues.

"When I was graduated in June, I intended to commence practicing right away, but I found that a rest was what I needed," Lytle said. "Ever since a small girl in High school I have been interested in politics, and hoped some day to be able to take an active part in shaping the great questions of the day."

In fall 1898 Lytle announced that she would join the faculty at Central Tennessee. Newspaper accounts claimed that she was the only woman law instructor in the world. She served one session, 1898 - 1899, in that position.

In 1910 Lytle was living in Brooklyn, New York, with her husband, Alfred C. Cowan, also a lawyer. The couple attended the annual convention of what is now known as the Negro Bar Association in 1913. Media stories said she was the first African American female to become a member of a national bar organization and the first to participate with a spouse.

Lytle returned to Topeka in 1925 and addressed a large audience at St. John's A.M.E. Church, which she had attended in her youth. Lytle told her audience about the progress of African Americans in New York City. She shared examples of integration in the schools and government and told of the vision of Marcus Garvey, considered the father of contemporary Black Nationalism.

She died on November 12, 1955 in Brooklyn and is buried at Saint Charles Cemetery in Suffolk County, New York.

Others in the Lytle family also were well known in Topeka. Lutie's father, John, was a barber in downtown Topeka and also worked as a policeman. Lutie's brother, Charles, operated barbershops at 109 West Fifth and 326 Kansas Avenue. He later opened a drug store in 100 block of East Fourth. Charles had a lengthy career in law enforcement, which included police detective, chief of detectives, and deputy state fire marshal where he held a record for most convictions in arson cases at 236.

Source: Kansapedia: Kansas Historical Society

Mary A. Burwell

| |

|

For the special care of orphan children there is a peculiar fitness, not at all possessed by the majority, either as an acquired or as an inherited possession. As an earnest laborer in this field among the poor, needy children of the race few of our young women have been more active, according to opportunity, than "Little Mary" Burwell, who was born in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, of (recently) slave parents living in humble circumstances. Her mother, though in very poor health, was nevertheless kind and affectionate, and no doubt would have willingly done all possible in the discharge of her duty towards her only child. However, an uncle of this "only child" came on a visit and was so attracted by the lovable disposition of Mary, asked for her and, upon promise of educating her in the city schools of Raleigh, North Carolina his request was granted, and he and little Mary were soon in the "City of Oaks," where she entered the Washington School at about eight years of age. After spending some time in the primary school she entered Shaw University, from which she graduated after remaining therein six years, taking a diploma from the Estey Seminary course.

She was a member of several classes taught by the author, while upon the faculty of Shaw University, who was always impressed with her meek yet earnest disposition as a student. After graduating she taught for several years in the public schools. She was then called as lady teacher to the orphanage at Oxford, NC., which position she accepted and gave up her school out of a desire to do something to help that struggling asylum, notwithstanding she knew it to be heavily burdened with debt and without one dollar in its treasury. She said, ''Any assistance I can render in the work it will be my pleasure to do so."

Did she expect pay from this institution in the shape of a big salary? No none was offered, as there was nothing to offer her as an inducement. In June, 1890, she entered upon her new work without any promise of earthly reward. Then the asylum consisted of one wood building of three rooms, containing eight little children. It was indeed a poor home. Finding talent among these children, she began to train them for concerts with a hope of getting better quarters for them. In July, just about one month from the time she went there, she took them out to travel. They created much interest through the State.

The General Assembly of North Carolina gave the institution $1,000, and up to November, 1892, less than two and one-half years, she has raised an additional sum of more than $1,500, and has also solicited many annual contributors who will continue to give. So she has done much to help furnish and build additional rooms. Now, instead of one building with three rooms containing eight children, there are many new additional rooms, well furnished with comforts, enjoyed by forty children. Miss Burwell has given new life to things in general at the Colored Asylum at Oxford. She is yet young in years, and has visited most points of interest in the State with these children, holding concerts and soliciting aid for the school, having not a dollar with which to start except previous savings.

Source: Women of Distinction written in 1893 by Lawson Andrew Scruggs (Scruggs was one of the first three African American doctors licensed in North Carolina).

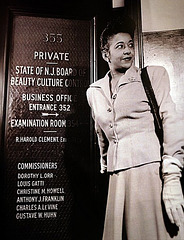

Christine Moore Howell

| |

|

For twenty-eight years Christine Moore Howell (1901 - 1972), catered to a very high class and particular clientele. Adjoining her salon was a laboratory where she produced her hair and skin care products. Clients came from great distances to take advantage of her special talent for cutting curly hair. In 1935 Mrs. Howell helped to create New Jersey's State Board of Beauty Culture and served as a State Commissioner of the Board of Beauty Culture Control. And was elected Chairman of the commission for three terms. In 1936 she wrote, the "Beauty Culture and Care of the Hair."

Sources: Monkmeyer Press Photo Service; Courtesy of Anita Duncan

Ethelyn Taylor Chisum

| |

|

She was born to William Henry and Virgie Collins Taylor in Dallas, Texas, where she spent her formative years. Following graduation from Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College May 1913, where Ethelyn M. Taylor was senior class historian, she began her teaching career in the Rock Creek community of Smith County, Texas. Almost three years later she returned to Dallas and a lifetime as an educator, thirty-two years of which were spent as counselor at Booker T. Washington High School.

In 1923, she married Dr. John Chisum who was born in 1895, to Benjamin Chisum and Rosa Pauline White. Following his 1916 graduation as salutatorian of Dallas Colored High School, Dr. Chisum worked as a mortician prior to military service in France during World War I. It was a union that lasted fifty-five years until his death in 1979.

Community service was an integral part of life for Mrs. Chisum, with membership in Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, as well as the Priscilla Art Club, oldest club for Negro women in Dallas. She was a long time member and active worker of the New Hope Baptist Church while Rev. A. S. Jackson, Sr. was pastor; later Dr. and Mrs. Chisum joined Knight's Chapel A.M.E. Church. Mrs. Chisum was often chosen as a leader of Dallas organizations such as the Dallas Teachers Council, serving the group as president for ten years. Realizing the need for a YWCA to serve the black community, Mrs. Chisum was one of the founders in 1927 of the Maria Morgan Branch of YWCA. She was repeatedly honored by local organizations for community service as well as being listed in Who's Who in Education in America. In 1967, two years after retirement from the Dallas Independent School District, Mrs. Chisum joined the staff of Southern Methodist University to work with the Upward Bound program jointly sponsored by the university and the United States Department of Education. She continued her association with SMU until failing health forced her retirement in November of 1982. In an effort to upgrade the teaching profession, Mrs. Chisum often worked as an appointed committee member for the National Education Association as well as the Texas Education Association. Working alongside Dr. John Chisum, her husband of more than fifty years, Ethelyn Chisum strove to improve educational opportunities as well as the quality of life for the youth of Dallas until her death, January 27, 1983.

Source: The Face of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial America to the Present edited by Kathleen Thompson and Hilary Mac Austin

Give All Women the Right to Vote

| |

|

Because of the Southern strategy adopted by much of the white women suffrage movement, Black women formed their own organizations to fight for the right to vote and then exercise that right. The organization shown here had its headquarters in Georgia in the early part of the 20th century.

Racist policies often kept African-American women out of the suffragist movement. The headquarters of Colored Women Voters, located in Georgia, was one of many early 20th-century organizations that fought for African-American suffrage.

Sources: The Face of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial America to the Present edited by Kathleen Thompson and Hilary Mac Austin; CUNY

Atholene Peyton

| |

|

Miss Atholene Peyton (1880-1951), was the author of the earliest Kentucky cookbook written by an African American. Her father was Dr. W. T. Peyton, a well known practitioner and educator.

Her book, 'Peytonia Cook Book,' was published in Louisville in 1906. She had deep roots in the city. Peyton was an 1897 graduate of Louisville's Central Colored High School and then went on to the Colored Normal School. She served on the domestic science faculty of the segregated Central Colored High School and was the faculty sponsor of the Girls' Cooking Club. In one of her applications on file om the Jefferson County Public schools archives she noted under "honors": Wrote the first Negro Cook Book in Kentucky." Her career at Central Colored High School lasted from 1904 until her death in April 1951. Peyton also taught domestic science at the Neighborhood Home and Training School for Colored Boys and Girls, located on Fifteenth Street in Louisville. The Training School was supported by the Neighborhood Circle of the King's Daughters. Peyton also represented the Louisville schools at an event in Frankfort featuring Dr. Booker T Washington, held to commemorate the construction of a new dormitory at Kentucky State University, from which she earned a degree in 1935.

Peyton also served on the domestic science faculty of the summer Chautauqua of the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington DC. This was organized by the Woman's Convention, an auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention, which was and remains an important African American religious organization. The president of the training school was the well known African American educator Nannie Helen Burroughs, who advocated for the improvement of African American women's marketable skills.

According to a news item in the Indianapolis Freeman (1907), The Peytonia Cook Book "has achieved a wonderful degree of popularity among the best authorities on the culinary art." The cookbook itself includes a warm introduction by Nannie Helen Burroughs.

Sources: Kentucky's Cookbook Heritage: Two Hundred Years of Southern Cuisine and Culture, written by John van Willigen (2014); Colored American Magazine (1906 edition)

Sarah Parker Remond

| |

|

In 1853, Sarah Remond (1826 - 1894), was forcibly removed and pushed down a flight of stairs at the Howard Athenaeum in Boston, Massachusetts where she had gone to attend the opera, Don Pasquale, for which she had purchased a ticket. This incident stemmed from her refusal to sit in a segregated section for the show. Remond sued for damages and won her case.

In 1856, the American Anti-Slavery Society hired a team of lecturers, including Remond, her brother Charles Lenox Remond, a well-known antislavery lecturer in the United States and Great Britain, and Susan B. Anthony to tour New York State addressing anti-slavery issues.

Sarah proved to be such a good speaker, and such a good fundraiser, that she was invited to take the anti-slavery message to Great Britain, something her brother had done ten years before. Accompanied by Samuel May, Jr., she sailed for Liverpool on December 28, 1858 from Boston on the steamer Arahia to enlist the aid of the English people in the American antislavery movement.

Before she sailed, she told Abby Kelly Foster, she feared not "the wind nor the waves, but I know that no matter how I go, the spirit of prejudice will meet me." In fact, she met with acceptance in Britain. "I have been received here as a sister by white women for the first time in my life,” she wrote; "I have received a sympathy I never was offered before." She spoke out against both slavery and racial discrimination, stressing the sexual exploitation of black women under slavery. At Tuckerman Institute on January 21, 1859, Remond gave her first antislavery lecture on the free soil of Britain. Without notes she eloquently spoke of the inhuman treatment of slaves in the United States.

Her stories of these atrocities shocked many of her listeners, bringing tears to the eyes of the British. She played an important role in drawing the attention of British abolitionists to the problems endured by free Blacks as well throughout the United States. In her short autobiography, written in 1861, she stressed that "prejudice against colour has always been the one thing, above all others, which has cast its gigantic shadow over my whole life."

While giving the speeches she found time to attend Bedford College for Ladies in London. She studied French, Latin, English literature, music, history and elocution. During her years in Britain, she combined lecturing with studying at the Bedford College for Ladies (now part of the University of London).

Remond visited Rome and Florence on several occasions while living in England. In 1866, she left London and entered the Santa Maria Nuova Hospital in Florence, Italy as a medical student at the age of 42. She became a doctor and married an Italian, Lazzaro Pinto from Sardinia, on April 25th, 1877, and as far as is known, never returned to the United States. (In fact, two of her sisters joined her in self-imposed exile.) She practiced medicine in Florence, Italy, for more than twenty years.

Sarah Remond died on December 13, 1894 in Italy. She was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Source: Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia Vol 1 and 2, edited by Darlene Clark Hine

Josephine Turpin Washington

| |

|

As a writer and educator, Josephine Washington was committed to freeing America from what she described as the "monster of prejudice whose voracious appetite is appeased only when individuals are reduced to abject servitude and are content to remain hewers of wood and drawers of water." Washington was concerned with social issues from an early age, and in her teaching and many writings she was a powerful advocate of women's rights and racial justice.

Born on July 31, 1861, in Goochland County, Virginia, Washington was the daughter of Augustus A Turpin and Maria V Crump-Turpin. Her father was the son of a former African slave named Mary and Edwin Durock Turpin (1783–1868), a grandson of Mary Jefferson Turpin. Washington was a great-granddaughter of Mary Jefferson Turpin, a paternal aunt of Thomas Jefferson.

Her education began at home and continued through normal and high schools to the Richmond Institute, which later became the Richmond Theological Seminary. She entered Howard University's college department and graduated in 1886. While at the university, Washington spent her summer vacations working as a copyist for Frederick Douglass, during his tenure as recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia. Following her marriage to Dr. Samuel H. H. Washington, a practicing physician in Birmingham. She moved to Birmingham in 1888. She later taught at Richmond Theological Seminary, Howard University, and Selma University, Alabama. Her commitment to education led Washington to play an important role in the development of Selma University, an educational institution for teachers and ministers alike.

Washington's literary efforts began as a teenager. Her first story, "A Talk about Church Fairs," in which she criticized the sale of wine at church fund-raisers, was published in the Virginia Star—to a favorable reaction—when she was only sixteen years old. While her writing, and perhaps especially her poetry, has largely been neglected, Washington addressed herself to many of the important issues of her day. Essays such as "Higher Education for Women," published in the People's Advocate, and her introduction to Lawson A. Scrugg's Women of Distinction (1893) display her concern with an array of issues affecting black people, including job opportunities, education, motherhood, and relations between women and men. In the latter essay she powerfully defends the "progressive woman" who seeks to successfully participate in both professional and domestic spheres. While chairperson of the Executive Board of the Alabama State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, Washington also wrote their Federation Hymn, "Mother Alabama." Her work appeared in numerous publications, including the New York Freeman, the New York Globe, the AME Review, the Christian Recorder, the Virginia Star, the Colored American Magazine, and the People's Advocate.

Writing in 1904 for the Colored American Magazine on the sixth annual meeting of the State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, held in Mobile, Alabama, Washington reported not only on the delegate's focus on black womanhood, standards of morality, and the setting up of a youth reformatory but also on the pervasive effects of segregation and racial prejudice within the city itself. With an eye to discrimination on all levels of society, Washington noted, for instance, the playgrounds that were set aside for the exclusive use of white children, while black children "look on longingly, but dare not touch the sacred structure."

Washington's numerous writings remain as testimony to her religious faith, her belief in the equality of women, and her strong commitment to ending racial discrimination.

She died on March 17, 1949, at the age of eighty-seven at her daughter’s home in Cleveland, Ohio.

Sources: The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, by Irvine Garland Penn; Colored American Magazine (1904 issue)

Louise De Mortie

| |

|

She has been slighted by historians although she was one of the most important African Americans of her time. "De Mortie's life stands as one of the foundations in which advancements of African Americans was built. Giving up her prosperous and happy life in Boston, she undertook the selfless and difficult task of caring for homeless and indigent children in a southern city that was foreign to her."

Louise De Mortie, born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1833, was well known as a lecturer, reader and persuasive public speaker who first made her mark in the exclusive social circles of Boston, Massachusetts. She was born into a high achieving family of free people of color. She moved to Boston in 1853 as did her future husband, John Oliver (1821 - 1899) a free black carpenter and an abolitionist from Petersburg, Virginia. They divorced sometime in 1862. Sources do not indicate that De Mortie ever remarried and there is no mention of surviving children.

From 1865 until her death, De Mortie continued her work as a fundraiser for the orphanage, traveling to Boston, Philadelphia and other northern cities where she was well known to raise funds for the institution. It was necessary for her to do this because of the difficulties the orphanage experienced at the end of the Civil War and after the assassination of President Lincoln. Andrew Johnson (Lincoln's vice president) did not support the previous administration's humanitarian stance. At the time of the new administration's defunding, it was proposed that the orphans were to be apprenticed to various employers (likely plantation owners) until the age of 15 for females and 18 for males. This would reinstate de facto enslavement for the orphaned children ... akin to reversing emancipation for black children who lacked parental support. With this huge upheaval the orphans narrowly escaped being apprenticed by the government to their former owners, by being moved to Marine Hospital, still under the protection of the Freedman’s Bureau, while funds continued to be raised.

She died on October 10, 1867, in New Orleans during a yellow fever epidemic.

Sources: National Anti-Slavery Standard, October 26, 1867; Notable Black American Women, Book 2 by Jessie Carney Smith; Sacred Ground by A. Craig Fisher, Ph.D.

Lucy Hughes

| |

|

Miss Lucy Hughes ran the Climax Café and Ice Cream Parlor on N. Main in the early 1900s, where she sold “hot and cold lunches at all hours,” while residing with her mother, son, brother, and one male lodger who worked as a kitchen helper. She remained in business until 1917.

Ad for her shop reads:

The Climax Cafe and Ice Cream Parlor

Hot and Cold Lunches at All Hours

Also, Nice Clean Rooms

Miss Lucy Hughes, Proprietress

273 N. Main St.

Memphis, Tenn

She died on September 1, 1918 in Memphis at the age of 45 of bladder cancer. She was laid to rest in Zion Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

Source: Restaurant-ing through history blog, by Jan Whitaker

Lovie Yancey

| |

|

LA Times

Feb. 2, 2008

Dennis McLellan

Lovie Yancey (1912 - 2008), was the founder of the Fatburger restaurant chain, which began with a popular post-World War II hamburger stand in South Los Angeles.

Yancey had already operated a restaurant in Tucson and was living in Los Angeles in the late 1940s when she began thinking about launching a new food business.

“I settled on hamburgers because they were the fastest-selling sandwich in America,” she told the Wave newspaper in 1985.

Yancey launched her foray into fast food by partnering with Charles Simpson, who worked for a construction company and reportedly used scrap materials to build a three-stool hamburger stand on Western Avenue near Jefferson Boulevard.

Opened in 1947, the business was called Mr. Fatburger. “The name of the store was my idea,” Yancey said. “I wanted to get across the idea of a big burger with everything on it … a meal in itself.”

In 1952, Yancey shed both her business partner and the “Mr.” in the hamburger stand’s name, and Fatburger was officially born.

From the beginning, Yancey was a fixture at the original Fatburger, where customers, who included entertainers such as Redd Foxx and Ray Charles, could custom-order their burgers.

“I worked 16, 17 and 18 hours a day behind the counter, seven days a week,” Yancey recalled in the 1985 interview. “I’d come home, catch a few hours of sleep and start all over again.”

Yancey didn’t start out operating an open-all-night hamburger stand, she said in the interview, “but as word got out how good the food was, we started getting requests from night shift and early morning workers – bus drivers, mailmen, street sweepers – to stay open longer.”

In 1973, Yancey opened a Fatburger on La Cienega Boulevard in Beverly Hills, and it became a favorite destination for celebrity burger buffs.

Fatburger even once made David Letterman’s Top 10 list for things he’d miss most about leaving Los Angeles.

In 1981, Yancey began offering franchises in what was billed as “The Last Great Hamburger Stand.”

By 1985, in addition to four company locations, there were 15 Fatburger franchise sites. “I don’t worry about McDonald’s, Burger King or Wendy’s,” Yancey told the Wave. “They may be more popular, but a good hamburger sells itself, and I don’t think anybody makes as good a hamburger as we do.”

For three consecutive years, beginning in 1985, Fatburger was named in Entrepreneur magazine’s annual Franchise 500 list.

Yancey sold her Fatburger company to an investment group in 1990 but retained control of the original property on Western Avenue. The stand was never designated as a Los Angeles historical-cultural monument.

Yancey, established a $1.7 million endowment at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte in 1986 for research into sickle-cell anemia. This was in fulfillment of a promise to her 22-year-old grandson, Duran Farrell, who had died of the disease three years earlier.

She died at the ripe old age of 96. In addition to a daughter, she is survived by three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Ethel Bailey Furman

| |

|

Photographed In 1928, these individuals attended the Negro Contractors' Conference at Hampton Institute, in Virginia. The central figure is Ethel Bailey Furman (1893–1976). Furman was probably the first practicing female African American architect in the Commonwealth of Virginia. She was born in Richmond and studied in New York and Chicago. Furman designed numerous public and private buildings in Richmond and the surrounding area including Fair Oak Baptist Church in Richmond and Mount Nebo Baptist Church in New Kent County.

Sources: Ethel Bailey Furman, Papers and Architectural Drawings, 1928-2003; Courtesy Personal Papers Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

Coretta Scott King

| |

|

Coretta Scott was born in Heiberger, Alabama and raised on the farm of her parents Bernice McMurry Scott, and Obadiah Scott, in Perry County, Alabama. She was exposed at an early age to the injustices of life in a segregated society. She walked five miles a day to attend the one-room Crossroad School in Marion, Alabama, while the white students rode buses to an all-white school closer by. Young Coretta excelled at her studies, particularly music, and was valedictorian of her graduating class at Lincoln High School. She graduated in 1945 and received a scholarship to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

As an undergraduate, she took an active interest in the nascent civil rights movement; she joined the Antioch chapter of the NAACP, and the college's Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. She graduated from Antioch with a B.A. in music and education and won a scholarship to study concert singing at New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

In Boston she met a young theology student, Martin Luther King, Jr., and her life was changed forever. They were married on June 18, 1953, in a ceremony conducted by the groom's father, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr. Coretta Scott King completed her degree in voice and violin at the New England Conservatory and the young couple moved in September 1954 to Montgomery, Alabama, where Martin Luther King Jr. had accepted an appointment as Pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

They were soon caught up in the dramatic events that triggered the modern civil rights movement. When Rosa Parks refused to yield her seat on a Montgomery city bus to a white passenger, she was arrested for violating the city's ordinances giving white passengers preferential treatment in public conveyances. The black citizens of Montgomery organized immediately in defense of Mrs. Parks, and under Martin Luther King's leadership organized a boycott of the city's buses. The Montgomery bus boycott drew the attention of the world to the continued injustice of segregation in the United States, and led to court decisions striking down all local ordinances separating the races in public transit.

Dr. King's eloquent advocacy of nonviolent civil disobedience soon made him the most recognizable face of the civil rights movement, and he was called on to lead marches in city after city, with Mrs. King at his side, inspiring the citizens, black and white, to defy the segregation laws. The visibility of Dr. King's leadership attracted fierce opposition from the supporters of institutionalized racism. In 1956, white supremacists bombed the King family home in Montgomery. Mrs. King and the couple's first child narrowly escaped injury.

The Kings had four children in all: Yolanda Denise; Martin Luther, III; Dexter Scott; and Bernice Albertine. Although the demands of raising a family had caused Mrs. King to retire from singing, she found another way to put her musical background to the service of the cause. She conceived and performed a series of critically acclaimed Freedom Concerts, combining poetry, narration and music to tell the story of the Civil Rights movement. Over the next few years, Mrs. King staged Freedom Concerts in some of America's most distinguished concert venues, as fundraisers for the organization her husband had founded, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Dr. King's fame spread beyond the United States, and he was increasingly seen not only as a leader of the American civil rights movement, but as the symbol of an international struggle for human liberation from racism, colonialism and all forms of oppression and discrimination. In 1957, Dr. King and Mrs. King journeyed to Africa to celebrate the independence of Ghana. In 1959, they made a pilgrimage to India to honor the memory of Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of nonviolence had inspired them. Dr. King's leadership of the movement for human rights was recognized on the international stage when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. In 1964, Mrs. King accompanied her husband when he traveled to Oslo, Norway to accept the Prize.

In the 1960s, Dr. King broadened his message and his activism to embrace causes of international peace and economic justice. Mrs. King found herself in increasing demand as a public speaker. She became the first woman to deliver the Class Day address at Harvard, and the first woman to preach at a statutory service at St. Paul's Cathedral in London. She served as a Women's Strike for Peace delegate to the 17-nation Disarmament Conference in Geneva, Switzerland in 1962. Mrs. King became a liaison to international peace and justice organizations even before Dr. King took a public stand in 1967 against United States intervention in the Vietnam War.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Channeling her grief, Mrs. King concentrated her energies on fulfilling her husband's work by building The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change as a living memorial to her husband's life and dream. Years of planning, fundraising and lobbying, lay ahead, but Mrs. King would not be deterred, nor did she neglect direct involvement in the causes her husband had championed. In 1969, Coretta Scott King published the first volume of her autobiography, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr. In the 1970s, Mrs. King maintained her husband's commitment to the cause of economic justice. In 1974 she formed the Full Employment Action Council, a broad coalition of over 100 religious, labor, business, civil and women's rights organizations dedicated to a national policy of full employment and equal economic opportunity; Mrs. King served as Co-Chair of the Council.

In 1981, The King Center, the first institution built in memory of an African American leader, opened to the public. The Center is housed in the Freedom Hall complex encircling Dr. King's tomb in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of a 23-acre national historic site that also includes Dr. King's birthplace and the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he and his father both preached. The King Center Library and Archives houses the largest collection of documents from the Civil Rights era. The Center receives over one million visitors a year, and has trained tens of thousands of students, teachers, community leaders and administrators in Dr. King's philosophy and strategy of nonviolence through seminars, workshops and training programs.

Mrs. King continued to serve the cause of justice and human rights; her travels took her throughout the world on goodwill missions to Africa, Latin America, Europe and Asia. In 1983, she marked the 20th Anniversary of the historic March on Washington, by leading a gathering of more than 800 human rights organizations, the Coalition of Conscience, in the largest demonstration the capital city had seen up to that time.

Mrs. King led the successful campaign to establish Dr. King's birthday, January 15, as a national holiday in the United States. By an Act of Congress, the first national observance of the holiday took place in 1986. Dr. King's birthday is now marked by annual celebrations in over 100 countries. Mrs. King was invited by President Clinton to witness the historic handshake between Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Chairman Yassir Arafat at the signing of the Middle East Peace Accords in 1993. In 1985 Mrs. King and three of her children were arrested at the South African embassy in Washington, D.C., for protesting against that country's apartheid system of racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Ten years later, she stood with Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg when he was sworn in as President of South Africa.

After 27 years at the helm of The King Center, Mrs. King turned over leadership of the Center to her son, Dexter Scott King, in 1995. She remained active in the causes of racial and economic justice, and in her remaining years devoted much of her energy to AIDS education and curbing gun violence. Although she died in 2006 at the age of 78, she remains an inspirational figure to men and women around the world.

Sources: Louise Ozell Martin, Photographer, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present by Deborah Willis; Academy of Achievement, All Achievers, Coretta Scott King, Pioneer of Civil Rights

Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown

| |

|

Her 1912 wedding portrait.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown (1870 - 1961), was born in Henderson, North Carolina, but grew up in Massachusetts after her family moved from the South. She was educated in Boston and had planned to finish her college education when two events changed her life.

First, she met Alice Freeman Palmer, a prominent New England woman, who was so impressed by Hawkins' determination to get an education that she became Brown's benefactor. Then, in 1901, Brown returned to the South to teach in a country school that was supported by a Northern missionary society in the town of Sedalia, North Carolina.

"I have devoted my life to establishing for Negro youth something superior to Jim Crowism."

She arrived during the worst years of the Jim Crow era. Blacks had been disfranchised as well as segregated and there was little money available for black schools. When the school's funding ended after two years, Brown decided to remain in Sedalia to start her own school. She went north to raise money and returned with $100, which she used to open the Palmer Memorial Institute, an academic and industrial school for African Americans, in 1902.

Brown's life was a balancing act. She passionately hated segregation and continually sought ways around it. When she went to town to visit her doctor or lawyer, she would arrange to enter into their office immediately upon her arrival. Thus, she avoided sitting in the Jim Crow section of the waiting room. When her students went to the movies or other cultural events, she would rent the theater for the day so that they did not have to sit in the "colored" section.

To raise funds for the school, she wrote letters to potential supporters. Her students learned French, Latin, and other academic subjects. Brown prepared her students to be leaders of their race.

In addition to building her school, Charlotte Hawkins Brown was active in the women's club and suffragist movements. She later became president of the North Carolina Association of Colored Women's Clubs, and she helped organize voter registration drives for black women and tried to get white club women to back suffrage for black women.

She saw herself as part of the freedom struggle that was taking place in the black community. The Palmer Institute became an educational success and remained open until a decade after her death, in 1961.

Sources: Charles W. Wadelington and Richard F. Knapp, 'Charlotte Hawkins Brown and Palmer Memorial Institute; What One Young African American Woman Could Do.'

Who Is The Real Mary Elizabeth Bowser?

| |

|

For years the woman in this photograph was assumed to be the infamous spy, Mary Elizabeth Bowser. However, the photograph depicts a different Mary Bowser. She was photographed by C.R. Rees, in Petersburg, Virginia in 1900 (when the spy, Mary Elizabeth Bowser would have been in her sixties). This discovery was made by author Lois Leveen, who wrote the book, "The Secrets of Mary Bowser." I personally choose to use this image as a representation of Mary Elizabeth Bowser.

Mary Bowser was born into slavery in the household of John Van Lew, a wealthy hardware merchant in Richmond, Virginia. Van Lew's daughter Elizabeth freed Mary Bowser and all her father's other slaves after he died. Elizabeth Van Lew, who never married, was known as an eccentric who sometimes walked down the streets of Richmond, head bent to one side, holding conversations with herself. Some called her "Crazy Bet".

"Crazy Bet" Van Lew inherited a lot of money and her father's society connections. She used some of the money to send her former slave Mary Bowser to school in Philadelphia and later Elizabeth used her connections to get Mary Bowser a servant job in President Jefferson Davis' Confederate White House. To many Mary Bowser appeared to be uneducated and dull-witted. But she worked hard.

Sometimes Mary Bowser met with her old patron "Crazy Bet" at a farm outside Richmond. The spinster and the servant were not just exchanging recipes. Oh, no. They were spies.

"Crazy Bet" was the spymaster and Mary Bowser was one of her best agents -- part of a spy ring -- white, black, slave and free -- made up of servants, farmers, seamstresses, storekeepers, undercover Scottish abolitionists -- working in plain sight in the South for the North.

As the educated Mary Bowser dusted and served in the Confederate White House, she used her photographic memory to record military documents she found on the president's desk and conversations she overheard in the dining room.

Daily tasks could hide secrets -- in a basket of eggs one empty shell filled with military plans; a serving tray loaded with food and messages concealed in its false bottom; wet laundry hung up in code. For example, a white shirt beside an upside-down pair of pants meant "Gen. Hill moving troops to the west."

When the Civil War ended, the first Union flag in Richmond was raised from the roof of Crazy Bet's mansion. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant praised her service to the Union cause.

But Mary Bowser's story remained mostly untold, even in her family. Then in the 1960s an elderly cousin asked Mrs. McEva Bowser if she had ever heard of her husband's great great aunt Mary.

McEva Bowser: "And she said, 'Do they ever talk about Mary Elizabeth?' And I said, 'No, never heard of her.' And she said, 'Well, they don't ever talk about her 'cause she was a spy.'"

And she left a diary, a diary that McEva Bowser may have found in 1952 when her husband's mother died.

McEva Bowser: "I was cleaning her room and... I ran across a diary but I never had a diary and I didn't even realize what it was... And I did keep coming across (references to) Mr. Davis. And the only Davis I could think of was the contractor who had been doing some work at the house. And the first time I came across it I threw it aside and said I would read it again. Then I started to talk to my husband about it but I felt it would depress him. So the next time I came across it I just pitched it in the trash can."

But Mary Bowser's story survived anyway. It was retold by black researchers and recalled in the memoirs of others involved in the spy ring.

In 1995, 130 years after the War Between the States ended, Mary Bowser was admitted to the U.S. Army Intelligence Hall of Fame.

Sources: Gibbs Magazine: News, Opinions, and Ideas of African Americans

Dr. Ella Mae Piper

| |

|

Ella Piper (1884 - 1954), was born in Brunswick, Georgia the only daughter of Ned Bailer and Sarah Williams. Dr. Piper held annual Christmas tree parties for children of Dunbar Heights. Her mother, Sarah Williams, started this event in 1915. Thus began an institute over the years that grew from an original gathering of 15 little girls to some 600 boys and girls who romped over her lawn at 1771 Evans Avenue every December 25th.

When Dr. Piper’s mother died in 1926, Dr, Piper carried on the Annual Christmas Party with the assistance of many churches, businesses, and many community friends who assisted with contributions and gifts for the youngsters. The annual Christmas Tree Party has continued uninterrupted since Dr. Piper’s death through the faithful efforts of local citizens.

Dr. Ella Piper was known as a philanthropist. She was instrumental in helping young people in obtaining scholarships to attend Tuskegee Institute, using her personal money to help some of these students she was well known throughout the community and often aided elderly persons, particularly the underprivileged and handicapped. It was this interest, along with the interest of children that led her to leave her property to the City of Fort Myers for the benefit of “young children and senior citizens”.

“She had what I like to call a Rebel Spirit,” said Vivian Hill, A Franklin Park Elementary school teacher who has researched Piper. “She was the type that would show many people, “if I can do it, you can do it.”

But Piper is not remembered for her money or her ability to cross the color line. Nearly 35 years after her death, “Dr. Ella” is remembered for her giving spirit. “She helped in that quiet kind of way, meeting the simple needs of people,” said Ray Jackson Executive Director at the Dr. Ella Piper Center, an Elderly Services Agency established on the property that Dr. Piper left to the City of Fort Myers when she died of a stroke in 1954 at the age of 70.

For instance, a family fallen on hard times might wake up to find groceries on the doorstep or a couple celebrating many years of marriage would have their anniversary party financed by Piper.

Mary Ware remembers that when her oldest son, Walter was ready to go off to College, Piper gave him so much clothing that he was able to share with other students. “She was just down to earth,” said Ware, 79. “She was a beautiful lady in looks and her dealings with you. She loved her people.”

Piper's mother helped pay for her education at Spelman College in Atlanta and later at Professor Rohrer’s World famous Institute of Beauty Culture in New York City. Piper studied as a Beautician and a Podiatrist. Sometime after her graduation in 1915 Piper opened a Beauty Shop in New York City, Hill said. Some of Dr. Piper's clientele were very wealthy and included the wives of Inventors Thomas Edison and Henry Ford.

Mary Ware remembers working in Piper’s shop as a young girl, sweeping up on Saturdays. “She was always ready to help the less fortunate,” Ware said, “But she made her money with the white people.” She poured much of her money back into the community at large by helping to finance such buildings as Jones Walker Hospital, a hospital for blacks and Williams Academy, a local black public school, Hill said. She carried on a tradition started by her mother in 1915, one that still continues today The Annual Christmas Party. Hundreds of children annually gathered at Dr. Piper’s home on Evans Avenue to collect gifts, sing carols and hear the story of Christ’s Birth.

Piper filed for and received the state permission to function as a free dealer. That meant she could buy and sell property and conduct business without her husband’s approval. It was a right not many women white or black exercised at the time.

In addition to her salon, she also owned the Big Four Bottling Company in Fort Myers, which bottled soda and sold it for 4 cents a serving, Hill said. She also was one of the first women to own an automobile in Fort Myers and had a chauffeur, Hill said.

“She was a kind of pioneer both socially and financially,” said Patricia Bartlet, Executive Director of the Fort Myers Historical Museum.

In her will, she left her property to the city of Fort Myers, to be used for children, the poor and the elderly. The city chooses to use it for the elderly, building The Dr. Ella Piper Center there in 1976.

March 8, 2022 “Proclamation Day” honoed the legacy of Dr. Ella Mae Piper by Mayor Kevin Anderson

Dr. Ella Piper Center is a social service center for older clients. Sponsored programs include Foster Grandparents, Senior Companions, Senior Employment and Faith in Action (Transportation). Foster Grandparents offers opportunities to mentor, tutor, and care for children and youth with special needs. Senior Companions provides assistance and friendship to homebound elderly.

Source: The Dr. Piper Center for Social Services, Inc., article by Suzanne D. Jeffries

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest items - Subscribe to the latest items added to this album

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter