Kicha's photos

Aida Overton Walker

| |

|

Aida Overton Walker is a name that should be more familiar to vaudeville and theater lovers than it is for she was the foremost African-American star of her generation which comprised the early years of the 20th century. Her national and even international fame was such that she was a living legend of black show business and in fact her vision of a world with dignified and respected black show business artists who did not have to demean themselves onstage was years ahead of reality. Her work helping young black artists and especially black women to become super-achievers and her own remarkable talents as singer, dancer, actress, comedienne and choreographer caused her to be one of the most admired and respected black women in America.

Aida was born in 1880 in New York City and became known quickly for her talent as a dancer and singer as well as her great natural beauty. By 1895 she was a member of the famous black touring company disparagingly known as John Isham’s Octoroons and then joined the Black Patti Troubadours. This famous group was headed by Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, known as Sissieretta Jones, who became a famous soprano. She was called the “Black Patti” after the famous white soprano Adelina Patti, who was one of the foremost superstars of opera of her time. Her troupe, the Troubadours, consisted of a whole show that entertained black and sometimes also white audiences throughout the country. The show had some 40 performers but Adelina emerged as one of its leading stars.

In 1898 she joined the rapidly rising comedy team of Bert Williams and George Walker, being featured in all of their landmark black performances including The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), the very famous In Dahomey (1902), Abyssinia (1905) and Bandanna Land (1907). Walker and Overton married soon after they began performing together.

Her performance of Miss Hannah from Savannah in Sons of Ham caused a national sensation and furthermore Aida did the choreography for all of these big shows and emerged as the glue or catalyst that made the Walker-Williams shows work so well, as she worked behind the scenes with her husband supplying the themes and basic ideas for the shows, which then featured the great humor of Bert Williams. Although forgotten today, whereas Williams and Walker are more remembered, the three of them formed the most popular trio of “colored” entertainers in the world in the early years of the 20th century. Aida was also in demand as a choreographer for other shows such as Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson’s The Red Moon (1909).

In these shows, although she performed in blackface, Aida refused to play black plantation stereotypes and an essential part of her political activism was to make the black woman stand tall and be an object of dignity and respect, even though she would attempt to make this statement through comedy and song. She became a huge hit in England from 1902 to 1904 with In Dahomey and was frequently hired for major society parties because she became known as the Queen of the Cakewalk from her dancing in the show and the British wanted to learn this remarkable dance so-named because originally those black dancers who did it well might receive a cake for a prize. In 1903 she played a command performance at Buckingham Palace for King Edward VII which added to her international reputation.

In the midst of this success her husband allegedly contracted syphilis through affairs with other women and he collapsed during the run of Bandanna Land in 1908. She was able to fill in for her ailing husband, performing his part in drag and managing to save the company, but eventually he grew more ill and died in 1911 as the disease, which had symptoms of stuttering and memory loss was incurable at this time. Bert Williams went on to solo success with the Ziegfeld Follies and Aida was forced to develop into a solo artist as well, leading to her work as choreographer and featured star in Red Moon and she joined the famous African-American Smart Set Company in 1910 while her husband was still gravely ill. What she must have thought of her husband’s behavior is not recorded but her indomitable will to survive and continue her art and her work even despite his situation is clear. Ten days after her husband’s death she signed a contract to star with S. H. Dudley in an all-black traveling show. Walker was buried in his home town of Lawrence, Kansas, one of many black superstars of the time to die of syphilis which almost reached epidemic proportions in the black theatrical community around this time.

Her post-Walker career was also distinctive as she emerged as a female superstar and was often invited to prominent white social gatherings to demonstrate the latest dances suitable for such events. Only Bert Williams among other black performers was able to do this and to work with white performers. For example she played the lead in Oscar Hammerstein’s 1912 revival of Salome at the Victoria Theater in New York, a role she had essayed in the black theater since the initial Salome craze of the early years of the century.

Aida was also an activist for black causes years and years before this was something that was popularly accepted. She raised significant funds for the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls and worked to promote opportunities for young black women in the entertainment business through her connections. She hoped to promote a new generation of refined and elegant black performers free of the hamstringing stereotypes of the previous decades. To this end in 1913 and 1914 she promoted the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls and produced shows for these troupes to show black women as original creative talent. This she did despite suffering from a number of disabling illnesses that beset her after the death of her husband.

In the 1910s she was described by critics as “the best Negro comedienne today” and “the most fascinating and vivacious female comedy actress the Negro race has ever produced”. Her ability to mesmerize an audience and her standard numbers performed in drag which she perfected while filling in for her ailing husband were legendary. Indeed each of her performances in shows or in vaudeville featured one of her famous drag numbers.

And then just as suddenly it was all over. Just 34 years of age, Aida died quickly on October 1, 1914 from kidney failure and hundreds of people came to her house to honor her and to grieve. A true legend of black vaudeville and theater had passed. Every black female entertainer of note in this world owes a great debt to this pioneering entertainer who envisioned a world which honored and respected black talent and who died at the height of her fame.

Sources: James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Kansas City Museum Collection; Hall Studio (NY) , circa 1909

A. Means

| |

|

He was the only African American Hatter (Hatmaker) in Memphis, Tennessee in the late 19th century.

Mr. Means for years has run the only first class hat store owned exclusively by colored people. He and his son have had long experience in the hat business and their workmanship has been of such a character as to give this firm an enviable reputation in business circles. Mr. Means is one of our oldest and best known citizens and no man stands higher in the estimation of all classes. He is a man of considerable wealth and has a commodious home on South Cynthia street. He has always been a good citizen and has done his part to promote the same. An estimable wife and three children form his family circle.

Advert:

A. Means & Son, The Hatters,

Keep constantly on hand a select assortment of the Latest Styles of Soft Hats neatly cleaned, dyed and repaired. Mail and telephone orders promptly attended. Satisfaction Guaranteed, New Phone 2905, 125 Gayoso Ave., Memphis, Tenn.

Sources: The Bright Side of Memphis: A Compendium of Information Concerning the Colored People of Memphis, Tennessee, Showing Their Achievements in Business, Industrial and Professional Life and Including Articles of General Interest on the Race, by Green Polonius Hamilton (1908)] *GP Hamilton was Principal, of Kortrecht High School in Memphis, TN

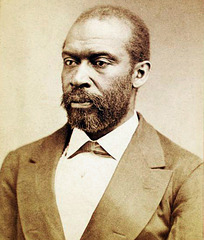

George Walker

| |

|

One half of the famous vaudeville team Williams and Walker.

"We want our folks the Negroes, to like us. Over and above the money and the prestige is a love for the race. We feel that in a degree we represent the race and every hair's breadth of achievement we make is to its credit." (1909)

“There is no reason why we should be forced to do these old-time nigger acts. It’s all rot, this slap--stick--bandanna handkerchief--bladder in the face act, with which Negro acting is associated. It ought to die out, and we are trying hard to kill it.” Walker said that over 110 years ago.

George Nash Walker was born in 1873 in Lawrence, Kansas. He left at a young age to follow his dream of becoming a stage performer and toured with a traveling group of minstrels. After performing at shows and fairs across the country, Walker met Bert Williams in 1893 and they formed the duo known as Williams and Walker. During this time, white men performing in minstrel shows blackened their faces to pose as black performers. As a counter, Williams and Walker billed themselves as “Two Real Coons,” a descriptor that marked the two as black men and a reference to the derogatory term “coon” used to describe people of African descent in the United States. While performing as a vaudeville act throughout the United States, George Walker and his partner Bert Williams popularized the cakewalk, an African American dance form named for the prize that would be earned by the winners of a dance contest.

There was a distinct difference in presentation styles between the two performers. While the light skinned Bert Williams donned blackface makeup, George Walker was known as a “dandy” who performed without makeup. While Williams played the role of the comic figure, George Walker played the straight man, a dignified counterpoint to the prevailing negative stereotypes of the time. Offstage, Walker was an astute businessman who managed the affairs of the Williams and Walker Company, a venture that brought them fame and wealth nationally and internationally. In 1903, they performed In Dahomey at Buckingham Palace in London and then toured the British Isles.

Working in collaboration with Will Marion Cook as playwright, Jesse Shipp as director, and Paul Laurence Dunbar as lyricist, Williams and Walker produced a musical called In Dahomey in 1902. In this play, with its original music, props, and elaborate scenery, Walker played a hustler disguised as a prince from Dahomey who was dispatched by a group of dishonest investors to convince blacks to join a colony. A landmark production, In Dahomey was the first all black show to open on Broadway. Another musical, In Abyssinia opened in 1906 in New York at the Majestic Theater. Both of these productions used African themes and imagery, making them unique for the time. Other Williams and Walker productions include: The Sons of Ham (1900), The Policy Players (1899), and Bandana Land (1908).

George Walker married Ada (Aida) Overton, a dancer, choreographer, and comedienne in 1899. Ada (Aida) Overton Walker was known as one of the first professional African American choreographers. After falling ill during the tour of Bandana Land in 1909, George Walker returned to Lawrence, Kansas, the city of his birth where he died on January 8, 1911. He was 38.

Sources: Louis Chude-Sokei, The Last “Darky”: Bert Williams, Black-On-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Kansas Historical Society

Aida Overton Walker

| |

|

Aida Overton Walker (1880-1914), dazzled early 20th century theater audiences with her original dance routines, her enchanting singing voice, and her penchant for elegant costumes. One of the premiere African American women artists of the turn of the century, she popularized the cakewalk and introduced it to English society. In addition to her attractive stage persona and highly acclaimed performances, she won the hearts of black entertainers for numerous benefit performances near the end of her tragically short career and for her cultivation of younger women performers. She was, in the words of the New York Age's Lester Walton, the exponent of "clean, refined artistic entertainment."

Born in New York City, where she gained an education and considerable musical training. At the tender age of fifteen, she joined John Isham's Octoroons, one of the most influential black touring groups of the 1890s, and the following year she became a member of the Black Patti Troubadours. Although the show consisted of dozens of performers, Overton emerged as one of the most promising soubrettes of her day. In 1898, she joined the company of the famous comedy team Bert Williams and George Walker, and appeared in all of their shows—The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), In Dahomey (1902), Abyssinia (1905), and Bandanna Land (1907). Within about a year of their meeting, George Walker and Overton married and before long became one of the most admired and elegant African American couples on stage.

While George Walker supplied most of the ideas for the musical comedies and Bert Williams enjoyed fame as the "funniest man in America," Aida quickly became an indispensable member of the Williams and Walker Company. In The Sons of Ham, for example, her rendition of Hannah from Savannah won praise for combining superb vocal control with acting skill that together presented a positive, strong image of black womanhood. Indeed, onstage Aida refused to comply with the plantation image of black women as plump mammies, happy to serve; like her husband, she viewed the representation of refined African American types on the stage as important political work. A talented dancer, Aida improvised original routines that her husband eagerly introduced in the shows; when In Dahomey was moved to England, Aida proved to be one of the strongest attractions. Society women invited her to their homes for private lessons in the exotic cakewalk that the Walkers had included in the show. After two seasons in England, the company returned to the United States in 1904, and it was Aida who was featured in a New York Herald interview about their tour. At times Walker asked his wife to interpret dances made famous by other performers—one example being the "Salome" dance that took Broadway by storm in the early 1900s—which she did with uneven success.

After a decade of nearly continuous success with the Williams and Walker Company, Aida's career took an unexpected turn when her husband collapsed on tour with Bandanna Land. Initially Walker returned to his boyhood home of Lawrence, Kansas, where his mother took care of him. In his absence, Aida took over many of his songs and dances to keep the company together. In early 1909, however, Bandanna Land was forced to close, and Aida temporarily retired from stage work to care for her husband, now clearly seriously ill. No doubt recognizing that he likely would not recover and that she alone could support the family, she returned to the stage in Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson's Red Moon in autumn 1909, and she joined the Smart Set Company in 1910. Aida also began touring the vaudeville circuit as a solo act. Less than two weeks after Walker's death in January 1911, Aida signed a two-year contract to appear as a co-star with S. H. Dudley in another all-black traveling show.

Although still a relatively young woman in the early 1910s, Aida began to develop medical problems that limited her capacity for constant touring and stage performance. As early as 1908, she had begun organizing benefits to aid such institutions as the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls, and after her contract with S. H. Dudley expired, she devoted more of her energy to such projects, which allowed her to remain in New York. She also took an interest in developing the talents of younger women in the profession, hoping to pass along her vision of black performance as refined and elegant. She produced shows for two such female groups in 1913 and 1914—the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls. She encouraged them to work up original dance numbers and insisted that they don stylish costumes on stage.

When Aida Overton Walker died suddenly of kidney failure on October 11, 1914, the African American entertainment community in New York went into deep mourning. The New York Age featured a lengthy obituary on its front page, and hundreds of shocked entertainers descended on her residence to confirm a story they hoped was untrue. Walker left behind a legacy of polished performance and model professionalism. Her demand for respect and her generosity made her a beloved figure in African American theater circles.

Sources: Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1890-1915. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, Thomas L Riis; Apeda Studio, NY.

Eliza Brooks

| |

|

Eliza Brooks was the aunt of famous opera singer Madame Lillian Evanti. Photo: Evans-Tibbs Collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Insititution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr

Image Speak

| |

|

The image is of Bert Williams, first black star of vaudeville.

Here her is as a caricature to please the masses. To make us more palatable to the masses tastebuds.

Facing Racism : Racial prejudice shaped Williams' career. Unlike many other blackface performers, Williams did not play for laughs at the expense of other African Americans or black culture. Instead, he based his humor on universal situations in which any members of his audience might find themselves. In the style of vaudeville, Williams performed in blackface makeup like his white counterparts. Blackface worked like a double mask for him. It emphasized the difference between Williams, his fellow vaudevillians, and his white audiences.

People sometimes ask me if I would not give anything to be white. I answer, in the words of the song, most emphatically, “No.” How do I know what I might be if I were a white man? I might be a sand-hog, burrowing away and losing my health for eight dollars a day. I might be a street-car conductor at twelve or fifteen dollars a week. There is many a white man less fortunate and less well equipped than I am. In truth, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have found it inconvenient—in America. How many times have hotel keepers said to me, ‘I know you, Williams, and I like you, and I would like nothing better than to have you stay here, but you see we have “southern gentlemen” in the house and they would object.’ Frankly, I can’t understand what it is all about. I breathe like other people, eat like them - if you put me at a dinner table you can be reasonably sure that I won’t use my ice cream fork for my salad; I think like other people.I guess the whole trouble must be that I don’t look like them. They say it is a matter of race prejudice. But if it were prejudice, a baby would have it, and you will never find it in a baby. It has to be inculcated on people. For one thing I have noticed that this ‘race prejudice’ is not to be found in people who are sure enough of their position to be able to defy it. For example, the kindest, most courteous, most democratic man I ever met was the king of England, the late King Edward VII. - Bert Williams

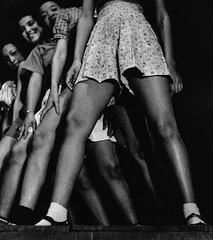

Rehearsal for a chorus line at the Apollo Theater

| |

|

Young African American women (names unknown) rehearse for the chorus line at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Lucien Aigner, Photographer

Since opening its doors in 1914 and introducing the first Amateur Night contests in 1934, the Apollo has played a major role in the emergence of jazz, swing, bebop, R&B, gospel, blues, and soul — all quintessentially American music genres. Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday, Sammy Davis Jr., James Brown, Bill Cosby, Gladys Knight, Luther Vandross, D’Angelo, Lauryn Hill, and countless others began their road to stardom on the Apollo stage. Today, the Apollo is a respected not-for-profit, which presents concerts, performing arts, education and community outreach programs.

The neo-classical theater known today as the Apollo Theater was designed by George Keister and first owned by Sidney Cohen. In 1914, Benjamin Hurtig and Harry Seamon obtained a thirty-year lease on the newly constructed theater calling it Hurtig and Seamon’s New Burlesque Theater. Like many American theaters during this time, African-Americans were not allowed to attend as patrons or to perform.

In 1933 Fiorello La Guardia, who would later become New York City’s Mayor, began a campaign against burlesque. Hurtig & Seamon’s was one of many theaters that would close down.

Cohen reopened the building as the 125th Street Apollo Theatre in 1934 with his partner, Morris Sussman serving as manager. Cohen and Sussman changed the format of the shows from burlesque to variety revues and redirected their marketing attention to the growing African-American community in Harlem.

Frank Schiffman and Leo Brecher took over the Apollo in 1935. The Schiffman and Brecher families would operate the Theater until the late 1970s.

The Apollo reopened briefly in 1978 under new management then closed again in November 1979. In 1981, it was purchased by Percy Sutton a prominent lawyer, politician, media and technology executive, and a group of private investors. Under Sutton’s ownership, the Theater was equipped with a recording and television studio.

In 1983, the Apollo received state and city landmark status and in 1991, Apollo Theater Foundation, Inc., was established as a private, not-for-profit organization to manage, fund and oversee programming for the Apollo Theater. Today, the Apollo, which functions under the guidance of a Board of Directors, presents concerts, performing arts, education and community outreach programs.

Source: apollotheater.org

William Donnegan

| |

|

William Donnegan, believed to be one of Springfield, Illinois' conductors on the Underground Railroad, was lynched during the 1908 Race Riot. This photo was originally published in the Chicago Record Herald ------ Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

William Donnegan, had been a prominent member of Springfield, Illinois' African American community since before the Civil War and was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He was lynched in the 1908 Springfield Race Riot.

According to an August 21, 1908, story in the weekly version of the Illinois State Register, Donnegan (spelled “Donnigan” by the newspaper) “was beaten almost to insensibility; his throat was slashed from ear with a razor and a small clothes line rope was tied about his neck, then he was hanged to the limb of a small tree” across from Donnegan’s home at Spring and Edwards streets.

The attack was broken up by police and state militia, but Donnegan died the next day at St. John’s Hospital.

The paper said the gang that attacked Donnegan’s home amounted to about a dozen men, apparently led by Abraham Raymer, a 20-year-old restaurant worker and peddler who had immigrated from Russia. Raymer was later found guilty only of stealing a sword.

Donnegan owned an estimated $15,000 worth of property at his death, a substantial amount for the time. Although he had been a cobbler and real estate investor, Donnegan also had made a pre-Civil War trade of importing slaves from the South and hiring them out as laborers in free-state Illinois. Whites resented his wealth and the fact that his third wife, Sarah Rudolph Donnegan, was white, the Register suggested.

Donnegan’s age at his death is open to question. Most accounts say he was either 76 or 84, but the Register’s reporter, who interviewed Donnegan’s family, gave an exact date for Donnegan’s birthday: March 16, 1828, making him 80 years old when he was killed. He is buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Mr. Donnegan is credited with writing a memoir of his role in helping an enslaved woman travel through Springfield to Canada in 1858.

The memoir, first published in 1898, was reprinted in the summer 2006 edition of “For the People,” the newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association. The original is available at the Sangamon Valley Collection at Lincoln Library.

“I lived, in those days, on the north side of Jefferson, between Eighth and Ninth streets, in a story and a half house. It is still standing, and I could show you the garret yet in which many a runaway has been hidden while the town was being searched. I have secreted scores of them, …” Donnegan wrote.

Image: Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

Info: Sagamon County History

Bertha Hansbury

| |

|

Bertha Allena Hansbury was born and educated in Detroit. After graduating from the Detroit Conservatory of Music, she did post-graduate work in Berlin, Germany. Upon her return to this country in 1909, she established a popular music studio where she taught over three hundred students. In 1925 she established the Bertha Hansbury School of Music at 544 Frederick in the Cultural Center.

After the end of slavery, African-American leaders focused much of their attention on education, seeking to lift up their students and achieve a measure of dignity and respect that had been previously denied them. Teachers and students seeking to raise up themselves and the broader Black community looked to existing educational models, many of which emphasized German language, philosophy, and music. Increasing numbers of students, most notably W.E.B. Du Bois but also musicians like Clarence Cameron White, Felix Weir, Will Marion Cook, and Hazel Harrison, also began traveling to Germany to pursue their studies, hoping to accrue cultural capital that they could deploy to help their communities rise up in the face of a system that still denigrated them.

Bertha Hansbury Phillips (1888-1976), was an important figure on the Detroit musical scene who sought out German study. After graduating from the Detroit Conservatory of Music in 1908, she studied in Berlin for a year. When she returned from Germany, Hansbury established a music studio in Detroit and in 1925 founded the first African-American music school in Michigan. She hoped “to give her people not only a place for the student class to attain cultural value” but also provide an opportunity for talented musicians and teachers to develop their talents when they might otherwise have laid them aside, “fearing there would be no future use for them.” The school was an important cultural institution for a time but was forced to close during the Great Depression.

Hansbury continued to exercise a broader influence not least through her daughter, Ruth (Aruthia Elizabeth Phillips) Mason (1923-2011). Mason became well-known as a disc jockey in Harlem and later helped develop the pathbreaking jazz label Blue Note Records, founded by her German husband Alfred Lion.

Sources: E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts, Detroit Public Library (detroityes.com) (E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts, Detroit Public Library); Black Central Europe, Jeff Bowersox.

Nancy Weston

| |

|

She lived in Charleston, South Carolina, in the 1850s as a free woman of color. However, in order to satisfy the laws of the state, she was a nominal slave legally owned by a white friend.

Nancy had three sons (Archibald who became an attorney, Francis who became a minister and John ) by her white enslaver Henry W. Grimké, a widower. Henry was a member of a prominent, large slaveholding family in Charleston. His father and relatives were planters and active in political and social circles. Henry acknowledged his sons, although he did not manumit (free) them, or make the rest of his family aware of their existence.

She was the grandmother of Harlem Renaissance writer Angelina Weld Grimké.

Sources: The Face of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial America to the Present edited by Kathleen Thompson and Hilary Mac Austin; Lift up Thy Voice: The Grimké Family's Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders by Mark Perry (2001)

Thomas Morris Chester: The Lone Black Reporter of…

| |

|

Born 1834, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The son of an escaped slave and oyster salesman, Chester’s childhood was relatively secure and very progressive. Attending college in Pittsburgh, he first became interested in the concept of African colonization and traveled back and forth between Liberia and the U.S. after graduation in 1853. Liberia was actually where Chester got his first taste of journalism, writing and editing for the “Star of Liberia” in Monrovia, the nation’s capitol.

The escalation of the Civil War prompted Chester to move back and join the Union efforts; he helped recruit and raise the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Colored troops regiments. Later, he would lead two Black regiments into battle for the famous Gettysburg Campaign in 1863. This was the first time Pennsylvania issued weapons to African-Americans.

From August 1864 to the end of the Civil War, Chester worked as a war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press, becoming the first Black war correspondent working for a major daily paper.

After the end of the war, Chester moved to England to study law and went on to become England’s first Black barrister (lawyer). During the 1870s, Chester moved back to the U.S. and settled in Louisiana, working as the brigadier general of the militia and also the superintendent of schools in 1875.

In 1892 embittered by Jim Crow laws and in ill health, he returned to his hometown, where he died of a heart attack a year later. He was buried in a segregated cemetery in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Newseum, Sharon Shahid

Image: Cheyney University of Pennsylvania

First Graders

| |

|

Class portrait of 1st Graders at Sumner Elementary School in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Standing in the doorway is school teacher Ms. Corsey, and Principal Fred Ramer.

A plaque located at 515 West Martin Street reads: The present building was completed in 1917 under the leadership of Fred R Ramer. He was the first principal in Berkeley County to have a school named after him. Ramer school served the black community until 1964. [Photo: A. O. & Dorothy Steele Collection]

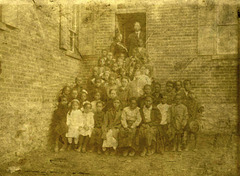

First Black School in Kansas

| |

|

This photograph shows a group of African American students and their teachers standing in front of the first black school in Kansas. The structure was located in Grasshopper Falls which is present day Valley Falls, Kansas. The photo is dated between the 1920s and 1930s. [kansasmemory.org]

Palmer Institute Faculty Members

| |

|

Founder Dr. Brown is in the center wearing eyeglasses. [Palmer Inst. Archives]

Palmer Institute founded by Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown was the only school for African American children in the area. Most walked a long way to reach the one-room schoolhouse. Students who could not pay for their education worked at the school. But all of the students had daily chores because Hawkins believed that working gave them a sense of responsibility.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown soon became a leader in the African American community both in North Carolina and across the country. She often spoke out against the unfair treatment of African Americans, and she fought for equality. She also supported women’s rights, including the right to vote.

Brown built Palmer Memorial Institute into an outstanding private school. Palmer highlighted cultural education and offered classes in drama, music, art, math, literature, and foreign languages. It attracted students from across the United States and from other countries. Brown saw more than one thousand students graduate from Palmer during her fifty years as president.

Following her death in 1961, the school had a hard time withstanding some financial problems, and in 1971 a fire destroyed the administration and classroom building forcing them to close.

In 1987, it was reopened as the Charlotte Hawkins Brown memorial State Historic site.

Lucille Berkely Buchanan

| |

|

Though Lucille Berkeley Buchanan was the first African American woman to graduate from the University of Colorado, her name and legacy were nearly lost to CU (Colorado University) history.

Thanks to the dogged detective work of a CU professor and the grass-roots support of students and faculty, this trailblazer is being remembered — and honored — with an endowed scholarship and, separately, an undergraduate essay prize.

Seven years ago, someone gave Polly McLean, an associate professor of journalism, a surprising newspaper clipping. The first black woman to graduate from CU had died in 1989 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Denver, it said.

Buchanan’s graduation date was 1918. But the first black woman to graduate from CU had long been identified as Ruth Cave Flowers, who graduated in 1924 and who later overcame significant racial barriers to become a school teacher.

As university archives, genealogical records, property records and other sources confirmed, Buchanan was actually the first, and her life was remarkable in its own right.

Born in 1884 in a mule barn southwest of Denver, Buchanan was the daughter of emancipated Virginia slaves. In 1905, her father built the Queen Anne house in which she spent her later years. It sat on land her mother bought from circus mogul P.T. Barnum.

Buchanan got a teaching certificate in 1905 from the Colorado State College for Education at Greeley. After teaching for a decade, she studied for a year at the University of Chicago. Then she came to CU. So it was that in June 1918, she became the first black woman to earn a degree from CU.

The moment was historic but sad; officials would not let her climb onstage to accept her diploma.

Afterward, she taught in the Chicago Public School system. She retired in 1949 and returned to Denver and the home her father had built. She died in a nursing home at the age of 105.

CU's German Program announced the first annual Lucile Berkeley Buchanan Undergraduate Essay Prize in spring of 2008.

The prize honors the fact that Buchanan was a German major, and it carries a $200 prize for the best paper originally written for a CU German class.

Source: Colorado University at Boulder

The Graduate

| |

|

Graduation photo of Marie S. Gordon, Class of 1915. Name of school she graduated from is unknown. [ Virginia Library ]

Class of 1891

| |

|

Pictured above was the first graduating class of Kortrecht High School, Class of 1891. Rebecca E. Driver, Fannie B. Turner, Gueiler D. Miller, Sarah E. Martin, and Katie L. Merriwether. Photographed by Tennessee's first black professional photographer, James P. Newton.

Kortrecht, the first brick building built for African American students, would eventually become Booker T. Washington High School. G. P. Hamilton was the first principal there and first principal of Booker T. Washington High School. Hamilton wrote "The Bright Side of Memphis" in 1908, spotlighting black Memphians who had made significant contributions to the city. Hamilton Elementary School, Hamilton Junior High, and Hamilton High are named in his honor.

Sources: Memphis Public Library

Clara Belle Williams

| |

|

Clara Belle Drisdale (1885-1994), was born in Plum, Texas in October 1885. She attended Prairie View Normal and Independent College (now Prairie View A & M University) in Prairie View, Texas beginning in 1903, and was valedictorian of her 1908 graduating class. She married Jasper Williams in 1917, and had three sons: Jasper, James, and Charles. Her husband died in 1946.

Williams took courses at the University of Chicago, and then enrolled at the New Mexico College of Agriculture & Mechanic Arts in the fall of 1928.

Taking courses only offered during the summer, while she worked as a teacher at Booker T. Washington School in Las Cruces, New Mexico, she graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in English from NMCA&MA in 1937 at the age of 51.

During a time when Las Cruces’s public schools were segregated, Mrs. Williams taught at the Booker T. Washington School for more than 20 years.

Mrs. Williams’ three sons all went to college and graduated with medical degrees. Charles attended Howard University Medical School in Washington D.C., Jasper and James graduated from Creighton University Medical School in Omaha, Nebraska. They went on to found the Williams Clinic in Chicago, Illinois.

Clara Belle Williams went on to receive many honors during her lifetime. She succeeded despite significant obstacles of discrimination placed before her while pursuing her higher education. In 1961, New Mexico State University named Williams Street on the main campus in her honor. She received an Honorary Doctorate of Laws degree from NMSU in 1980.

Clara Belle Williams Day was celebrated on Sunday, February 13, 2005 at NMSU. Included in the festivities was the renaming of the NMSU English Building as Clara Belle Williams Hall.

Mrs. Williams passed away July 3, 1994 at the age of 108.

Panorama New Mexico State University Alumni Magazine

By Karl Hill