Sonny Rollins

Marion 'Little Walter' Jacobs

Sidney Bechet and the Jazz Kings

The Tragic Teen Queens: Betty and Rosie Collins

Dolphy and Coltrane

Eddie James 'Son' House, Jr.

Carline Ray

Pee Wee Marquette

Lorraine Glover and Her Hubby's Horn

This Jazz Artist Was Included in the Holocaust Mem…

Lady Day

B'More's First Lady of Jazz: Ethel Ennis

1st African American to Reach No. 1 on the Billboa…

Lady in Sepia

Howlin the Blues

Ella Fitzgerald

A Teacher and her Pupils

The Graduate

Omega Sweetheart

Reading Group

Future Leaders

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas

Odessa Madre: The 'Al Capone' of DC

This is Louis

Sylvia Robinson

Mance Lipscomb

Madam N.A. Franklin

Carrie Lee

Catherine Robinson Gillespie

The Man Behind the Historical Morton Theater in At…

Cudjoe Kossula Lewis: "The Last African-American A…

Office Dallas

Pyrrhus Concer

Matilda McCrear: Was she the last.....?

James Mars

Palace Hotel

On the Way to a Lynching

Swingin with Lindy

Warrior Women

Una Mae Carlisle

Rose Marie McCoy

Chick Webb

Walter Barnes

Ginger Smock

Delta Blues Man: Charlie Patton

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

26 visits

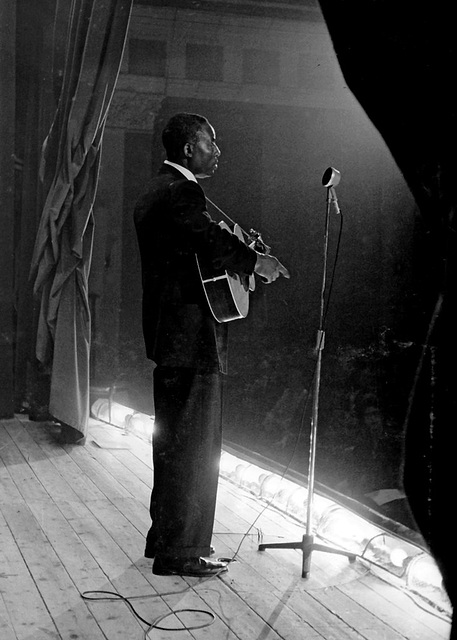

Bill Broonzy

Performing, probably at the Doelenzaal, Amsterdam, late November 1955.

"Well, I was born in Mississippi, in the year 18 and 93. I was born on a plantation and I stayed there until I was eight years old. Then my daddy and mother, they brought us — me and my twin sister and about eight more of us — to Arkansas — that was Langdale — Langdale, Arkansas."

The only true parts of that origin story are "born on a plantation" and "Arkansas." In fact, Langdale doesn't appear to exist anymore, if it was ever an actual place at all. And the sister he spoke of wasn't his twin, but the closest sibling by birth and sheer love, which in his interpretation and expression would pretty much make them twins.

Inventing a hometown, moving your birthplace to a neighboring state, and setting your birthday a decade earlier in another century takes a real character — like the one Lee Conley Bradley created for himself: Big Bill Broonzy. One of the quintessential blues artists of the 20th century and a key link in the chain from the early blues of the 1920s to the folk revival of the 1950s, Broonzy's contributions to American popular music cannot be overstated.

For an artist that remains relatively unknown today by even casual blues fans, his influence is staggering. This list includes, but is not limited to, Elvis Presley, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Muddy Waters, Pete Townshend and Ray Davies, who to this day never misses an opportunity to offer up praise and point out how The Kinks calling card "You Really Got Me" was his attempt at a great rhythm and blues song — something Big Bill Broonzy would play.

But before there was a Big Bill Broonzy, there was Lee Conley Bradley, who was born June 26, 1903, in Jefferson County, Arkansas, where he was raised with his nine siblings on a sharecropper plantation. That's just one of the revelations in Chicago-based author Bob Riesman's meticulously researched biography, "I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy" (The University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Riesman peels back the layers on a life story that may have been light on facts, but always had an essence of the truth. What emerges is an enlightening and highly enjoyable portrait of a man who seemingly always knew exactly who he was and where his trajectory lay in his immediate scene, in the lineage of roots music, and in the plight of rural, Southern African Americans.

Broonzy was blessed with a unique, emotive voice that could nimbly shift from a meditative, brooding drawl to rollicking, boisterous twang depending on the mood and the melody. His inimitable guitar playing functioned as an extension of his warm, expansive personality, creating a seamless presence with his skills as well as his look, manner and words. His affable nature and musical malleability would serve him well throughout his career.

Like most African Americans growing up in the segregated South under Jim Crow laws, Broonzy's early life was marked by blistering hard work, commitment to the church and little formal education. The education he did receive away from church and the schoolhouse was his earliest musical influence, Uncle Jerry Belcher, who was likely an amalgamation of older relatives and family friends since no historical records of him exist. Broonzy learned his earliest songs from listening to the decidedly non-church going Uncle Jerry play instruments created out of tubs, brooms and other household items. This might have inspired Broonzy's first instrument, a fiddle fashioned out of cornstalks brought back from the cotton fields where he toiled.

The young Broonzy joined up with like-minded friends, who played homemade fiddles and guitars, to form a string band. They spent their teenage years learning to play a variety of styles to satisfy the segregated audiences at weekend-long picnics and black audiences at stifling, packed juke joints.

In Broonzy's account of his formative years, he joined the U.S. Army in 1917 and fought in France during World War I. In the various versions of these events he presented in writings and interviews, Broonzy described the often degrading, humiliating experience faced by black soldiers who were subjected to the most menial jobs and received harsh punishment for any perceived slight. These stories he told not only detail the conditions during war, but also what a black man in uniform had to endure once he returned home where he was often viewed as a threat because of the respect he would likely be accorded. Broonzy described his initial return from battle when he was met in the street by a former employer who told him not to be parading around in "Uncle Sam's uniform." When he pleaded that he had no other clothes, the old boss told Broonzy that he still owed money and the only thing he could have was some overalls to work in so he could pay off his debt. It was an episode Broonzy would revisit in stark detail in his song, "When Will I Get to Be Called a Man?"

The facts that he would have been 14 at the start of the war, and that no draft registration card exists for him like there does for his brother, lead Riesman to conclude Broonzy never joined the military despite his richly detailed stories, which were most likely fabricated from the accounts of returning veterans. Yet, the episodes he shared were brutally accurate as they relate to the harrowing experience of black soldiers during and after the war.

"He made a decision to use himself, his family and others in the world that he grew up in and came from in Jefferson County, Arkansas, as ways of conveying to primarily white audiences the story of the African American experience in this country, particularly in the first half of the 20th century," Riesman told the Arkansas Times.

"He used his exceptional way with words both in songwriting and in other writings to speak out against racial injustice at a time when that was taking a significant professional risk for any musician and particularly an African American musician."

In the mid-1920s, Broonzy joined the migration of hundreds of thousands of African Americans traveling north to Chicago for the possibility of a better life. He quickly realized that playing a guitar would get you more work than being a country fiddle player, making a transition that would see him become one of the most gifted and prolific session musicians in the robust Chicago music scene of the 1930s. As he would at many other points in his life, Broonzy made connections to influential people that could provide recording opportunities with a variety of musicians and ensembles, including Georgia Tom Dorsey, Jazz Gillum, Lil Green, State Street Boys, Washboard Sam and Memphis Nighthawks.

"I think what Big Bill did extraordinarily well is chart his own course, even before he began his 30-year recording career in the late 1920s. At no point was there anyone that was formally his manager or in a position to say, 'I think you should go in this direction or play in this style,' " Riesman said. "He was able to identify the next musical trend, and he did so numerous times."

The capacity Broonzy had for connecting with people from all walks of life in a very profound and simple way is evident throughout his life, whether in the blues circuit of depression-era Chicago or playing with folk artists like Pete Seeger at colleges and summer camps in the 1940s or in the final years of his life spreading the gospel of blues to foreign audiences and admirers throughout Europe.

When Riesman first got the idea to write a book on blues or folk music, he admits he was not very familiar with Broonzy, but the name kept popping up in his research. He soon discovered he had selected a beguiling, confounding subject.

"Studs Terkel said about Bill that he is telling the truth — his truth," Riesman said. "That turned out to be a challenge I didn't know I'd be faced with but was a central challenge for a would-be biographer." As Riesman dug deeper into his initial research, he was puzzled by the incongruities in the life and timeline that Broonzy described and what historical records actually showed.

"Finally, I concluded, in the words of Winnie the Pooh, 'The more I looked for it the more it wasn't there,' " Riesman said.

The first clue to Broonzy's origin was found in a box of old letters in Amsterdam. While digging into the exploits and relationships Broonzy had experienced in Europe, Riesman interviewed Pim van Isveldt, who was Broonzy's Dutch girlfriend and the father of his only son.

"When Pim showed me an envelope containing a letter that Bill had sent to her, and the return address displayed in his handwriting the last name Wesley and a street address in North Little Rock, that was the first time I had come across any documentation that directly connected Bill with Arkansas," Riesman said.

A few months later, Riesman traveled to Little Rock where he scoured the Arkansas History Commission for new leads. He was able to locate the obituary of Lannie Bradley Wesley, who Riesman had recently learned was Broonzy's sister. A resourceful employee then suggested he attend the bible class held that evening at the church mentioned in the obituary. After asking a few people at the church about the family, he was soon handed a phone to speak with Broonzy's grandniece, Rosie Tolbert.

"My first thought was he's pulling my leg," Tolbert told the Times. "When they called me from down at church and said 'Rosie, there's this guy down here and he's writing a book about your uncle,' I said, 'Yeah right.' "

It didn't take Riesman long to convince Tolbert and her sister Jo Ann Jackson that he was sincere in his efforts. The sisters would spend the next several years sharing their family history with Riesman, in particular, a key document dating back to the late 1800s chronicling the Bradley family births, marriages and deaths, which clearly shows Lee Conley Bradley born in Arkansas in 1903.

"We always knew he was born here," Tolbert said. "I didn't know why he did the Mississippi thing, but he did grow up near Scott, Ark., and it probably just popped into his mind to say Mississippi."

Even though Tolbert and Jackson were young, they both have fond memories of the excitement that always surrounded their uncle's visits to North Little Rock.

"When Uncle Bill came home it was really a treat," Jackson said. "We'd party — I'd guess you would call it that. My grandmother would cook, Uncle Bill would play and we'd dance and have a good time."

The way Tolbert and Jackson described their uncle reflects the sentiments of his friends, associates and acolytes, including Muddy Waters who once described Broonzy as "the nicest guy I ever met in my life."

"He was the happiest person I think I've ever seen," Tolbert said. "He was just always happy, and he loved kids."

The success and notoriety Broonzy experienced in the latter part of his life as an ambassador bringing blues music and culture to international audiences was, in Riesman's view, perhaps his most powerful and lasting contribution. From the very beginning, Broonzy told his new audience that the only people who can sing the real blues are those who come from the kinds of rural conditions with mules, cotton fields and the types of circumstances he describes in his songs.

"The more I look at interviews he gave and articles written about him, particularly those first experiences in foreign countries, the more struck I was and am now at how masterfully he took on that role from the very beginning," Riesman said. "This was something there was no template for — he was not following in anybody's footsteps. There's no evidence as he was doing this that there was anything but a clear-sighted and resolute awareness of himself as someone who could do several things simultaneously and very well. Namely, he sets foot in England and he presents himself not just as a musician but as someone who could guide the listener to an understanding of the world the music came from — the world whose conditions produced the blues, and he's quite eloquent on that subject."

When Broonzy died from cancer in August of 1958, he was a very prominent figure, who rated an obituary in the New York Times, an article in Time, and a two-page spread and editorial in Ebony. Three years later, the first full LP compilation of Robert Johnson recordings was released to a rapturous response. What followed was a renewed appreciation and resurgence in blues music with many of the retired artists finding new touring and recording opportunities and even greater international acclaim.

While his stature in the pantheon of American blues and folk music might have declined over the years, Riesman sees a place for Big Bill Broonzy in the rich musical tradition of his home state.

"I think it would be wonderful if the state and people in the state and friends of the state could claim him as one of the many exceptional musicians to have come from Arkansas."

Sources: Michael van Isveldt Collection., Photographs from "I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy," by Bob Riesman, Arkansas Times by Jeremy Glover

"Well, I was born in Mississippi, in the year 18 and 93. I was born on a plantation and I stayed there until I was eight years old. Then my daddy and mother, they brought us — me and my twin sister and about eight more of us — to Arkansas — that was Langdale — Langdale, Arkansas."

The only true parts of that origin story are "born on a plantation" and "Arkansas." In fact, Langdale doesn't appear to exist anymore, if it was ever an actual place at all. And the sister he spoke of wasn't his twin, but the closest sibling by birth and sheer love, which in his interpretation and expression would pretty much make them twins.

Inventing a hometown, moving your birthplace to a neighboring state, and setting your birthday a decade earlier in another century takes a real character — like the one Lee Conley Bradley created for himself: Big Bill Broonzy. One of the quintessential blues artists of the 20th century and a key link in the chain from the early blues of the 1920s to the folk revival of the 1950s, Broonzy's contributions to American popular music cannot be overstated.

For an artist that remains relatively unknown today by even casual blues fans, his influence is staggering. This list includes, but is not limited to, Elvis Presley, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Muddy Waters, Pete Townshend and Ray Davies, who to this day never misses an opportunity to offer up praise and point out how The Kinks calling card "You Really Got Me" was his attempt at a great rhythm and blues song — something Big Bill Broonzy would play.

But before there was a Big Bill Broonzy, there was Lee Conley Bradley, who was born June 26, 1903, in Jefferson County, Arkansas, where he was raised with his nine siblings on a sharecropper plantation. That's just one of the revelations in Chicago-based author Bob Riesman's meticulously researched biography, "I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy" (The University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Riesman peels back the layers on a life story that may have been light on facts, but always had an essence of the truth. What emerges is an enlightening and highly enjoyable portrait of a man who seemingly always knew exactly who he was and where his trajectory lay in his immediate scene, in the lineage of roots music, and in the plight of rural, Southern African Americans.

Broonzy was blessed with a unique, emotive voice that could nimbly shift from a meditative, brooding drawl to rollicking, boisterous twang depending on the mood and the melody. His inimitable guitar playing functioned as an extension of his warm, expansive personality, creating a seamless presence with his skills as well as his look, manner and words. His affable nature and musical malleability would serve him well throughout his career.

Like most African Americans growing up in the segregated South under Jim Crow laws, Broonzy's early life was marked by blistering hard work, commitment to the church and little formal education. The education he did receive away from church and the schoolhouse was his earliest musical influence, Uncle Jerry Belcher, who was likely an amalgamation of older relatives and family friends since no historical records of him exist. Broonzy learned his earliest songs from listening to the decidedly non-church going Uncle Jerry play instruments created out of tubs, brooms and other household items. This might have inspired Broonzy's first instrument, a fiddle fashioned out of cornstalks brought back from the cotton fields where he toiled.

The young Broonzy joined up with like-minded friends, who played homemade fiddles and guitars, to form a string band. They spent their teenage years learning to play a variety of styles to satisfy the segregated audiences at weekend-long picnics and black audiences at stifling, packed juke joints.

In Broonzy's account of his formative years, he joined the U.S. Army in 1917 and fought in France during World War I. In the various versions of these events he presented in writings and interviews, Broonzy described the often degrading, humiliating experience faced by black soldiers who were subjected to the most menial jobs and received harsh punishment for any perceived slight. These stories he told not only detail the conditions during war, but also what a black man in uniform had to endure once he returned home where he was often viewed as a threat because of the respect he would likely be accorded. Broonzy described his initial return from battle when he was met in the street by a former employer who told him not to be parading around in "Uncle Sam's uniform." When he pleaded that he had no other clothes, the old boss told Broonzy that he still owed money and the only thing he could have was some overalls to work in so he could pay off his debt. It was an episode Broonzy would revisit in stark detail in his song, "When Will I Get to Be Called a Man?"

The facts that he would have been 14 at the start of the war, and that no draft registration card exists for him like there does for his brother, lead Riesman to conclude Broonzy never joined the military despite his richly detailed stories, which were most likely fabricated from the accounts of returning veterans. Yet, the episodes he shared were brutally accurate as they relate to the harrowing experience of black soldiers during and after the war.

"He made a decision to use himself, his family and others in the world that he grew up in and came from in Jefferson County, Arkansas, as ways of conveying to primarily white audiences the story of the African American experience in this country, particularly in the first half of the 20th century," Riesman told the Arkansas Times.

"He used his exceptional way with words both in songwriting and in other writings to speak out against racial injustice at a time when that was taking a significant professional risk for any musician and particularly an African American musician."

In the mid-1920s, Broonzy joined the migration of hundreds of thousands of African Americans traveling north to Chicago for the possibility of a better life. He quickly realized that playing a guitar would get you more work than being a country fiddle player, making a transition that would see him become one of the most gifted and prolific session musicians in the robust Chicago music scene of the 1930s. As he would at many other points in his life, Broonzy made connections to influential people that could provide recording opportunities with a variety of musicians and ensembles, including Georgia Tom Dorsey, Jazz Gillum, Lil Green, State Street Boys, Washboard Sam and Memphis Nighthawks.

"I think what Big Bill did extraordinarily well is chart his own course, even before he began his 30-year recording career in the late 1920s. At no point was there anyone that was formally his manager or in a position to say, 'I think you should go in this direction or play in this style,' " Riesman said. "He was able to identify the next musical trend, and he did so numerous times."

The capacity Broonzy had for connecting with people from all walks of life in a very profound and simple way is evident throughout his life, whether in the blues circuit of depression-era Chicago or playing with folk artists like Pete Seeger at colleges and summer camps in the 1940s or in the final years of his life spreading the gospel of blues to foreign audiences and admirers throughout Europe.

When Riesman first got the idea to write a book on blues or folk music, he admits he was not very familiar with Broonzy, but the name kept popping up in his research. He soon discovered he had selected a beguiling, confounding subject.

"Studs Terkel said about Bill that he is telling the truth — his truth," Riesman said. "That turned out to be a challenge I didn't know I'd be faced with but was a central challenge for a would-be biographer." As Riesman dug deeper into his initial research, he was puzzled by the incongruities in the life and timeline that Broonzy described and what historical records actually showed.

"Finally, I concluded, in the words of Winnie the Pooh, 'The more I looked for it the more it wasn't there,' " Riesman said.

The first clue to Broonzy's origin was found in a box of old letters in Amsterdam. While digging into the exploits and relationships Broonzy had experienced in Europe, Riesman interviewed Pim van Isveldt, who was Broonzy's Dutch girlfriend and the father of his only son.

"When Pim showed me an envelope containing a letter that Bill had sent to her, and the return address displayed in his handwriting the last name Wesley and a street address in North Little Rock, that was the first time I had come across any documentation that directly connected Bill with Arkansas," Riesman said.

A few months later, Riesman traveled to Little Rock where he scoured the Arkansas History Commission for new leads. He was able to locate the obituary of Lannie Bradley Wesley, who Riesman had recently learned was Broonzy's sister. A resourceful employee then suggested he attend the bible class held that evening at the church mentioned in the obituary. After asking a few people at the church about the family, he was soon handed a phone to speak with Broonzy's grandniece, Rosie Tolbert.

"My first thought was he's pulling my leg," Tolbert told the Times. "When they called me from down at church and said 'Rosie, there's this guy down here and he's writing a book about your uncle,' I said, 'Yeah right.' "

It didn't take Riesman long to convince Tolbert and her sister Jo Ann Jackson that he was sincere in his efforts. The sisters would spend the next several years sharing their family history with Riesman, in particular, a key document dating back to the late 1800s chronicling the Bradley family births, marriages and deaths, which clearly shows Lee Conley Bradley born in Arkansas in 1903.

"We always knew he was born here," Tolbert said. "I didn't know why he did the Mississippi thing, but he did grow up near Scott, Ark., and it probably just popped into his mind to say Mississippi."

Even though Tolbert and Jackson were young, they both have fond memories of the excitement that always surrounded their uncle's visits to North Little Rock.

"When Uncle Bill came home it was really a treat," Jackson said. "We'd party — I'd guess you would call it that. My grandmother would cook, Uncle Bill would play and we'd dance and have a good time."

The way Tolbert and Jackson described their uncle reflects the sentiments of his friends, associates and acolytes, including Muddy Waters who once described Broonzy as "the nicest guy I ever met in my life."

"He was the happiest person I think I've ever seen," Tolbert said. "He was just always happy, and he loved kids."

The success and notoriety Broonzy experienced in the latter part of his life as an ambassador bringing blues music and culture to international audiences was, in Riesman's view, perhaps his most powerful and lasting contribution. From the very beginning, Broonzy told his new audience that the only people who can sing the real blues are those who come from the kinds of rural conditions with mules, cotton fields and the types of circumstances he describes in his songs.

"The more I look at interviews he gave and articles written about him, particularly those first experiences in foreign countries, the more struck I was and am now at how masterfully he took on that role from the very beginning," Riesman said. "This was something there was no template for — he was not following in anybody's footsteps. There's no evidence as he was doing this that there was anything but a clear-sighted and resolute awareness of himself as someone who could do several things simultaneously and very well. Namely, he sets foot in England and he presents himself not just as a musician but as someone who could guide the listener to an understanding of the world the music came from — the world whose conditions produced the blues, and he's quite eloquent on that subject."

When Broonzy died from cancer in August of 1958, he was a very prominent figure, who rated an obituary in the New York Times, an article in Time, and a two-page spread and editorial in Ebony. Three years later, the first full LP compilation of Robert Johnson recordings was released to a rapturous response. What followed was a renewed appreciation and resurgence in blues music with many of the retired artists finding new touring and recording opportunities and even greater international acclaim.

While his stature in the pantheon of American blues and folk music might have declined over the years, Riesman sees a place for Big Bill Broonzy in the rich musical tradition of his home state.

"I think it would be wonderful if the state and people in the state and friends of the state could claim him as one of the many exceptional musicians to have come from Arkansas."

Sources: Michael van Isveldt Collection., Photographs from "I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy," by Bob Riesman, Arkansas Times by Jeremy Glover

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter