Sylvia Robinson

This is Louis

Bill Broonzy

Sonny Rollins

Marion 'Little Walter' Jacobs

Sidney Bechet and the Jazz Kings

The Tragic Teen Queens: Betty and Rosie Collins

Dolphy and Coltrane

Eddie James 'Son' House, Jr.

Carline Ray

Pee Wee Marquette

Lorraine Glover and Her Hubby's Horn

This Jazz Artist Was Included in the Holocaust Mem…

Lady Day

B'More's First Lady of Jazz: Ethel Ennis

1st African American to Reach No. 1 on the Billboa…

Lady in Sepia

Howlin the Blues

Ella Fitzgerald

A Teacher and her Pupils

The Graduate

Omega Sweetheart

Reading Group

Madam N.A. Franklin

Carrie Lee

Catherine Robinson Gillespie

The Man Behind the Historical Morton Theater in At…

Cudjoe Kossula Lewis: "The Last African-American A…

Office Dallas

Pyrrhus Concer

Matilda McCrear: Was she the last.....?

James Mars

Palace Hotel

On the Way to a Lynching

Swingin with Lindy

Warrior Women

Una Mae Carlisle

Rose Marie McCoy

Chick Webb

Walter Barnes

Ginger Smock

Delta Blues Man: Charlie Patton

The Six Teens

Billie Holiday

The Sassy One: Sarah Vaughan

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

15 visits

Mance Lipscomb

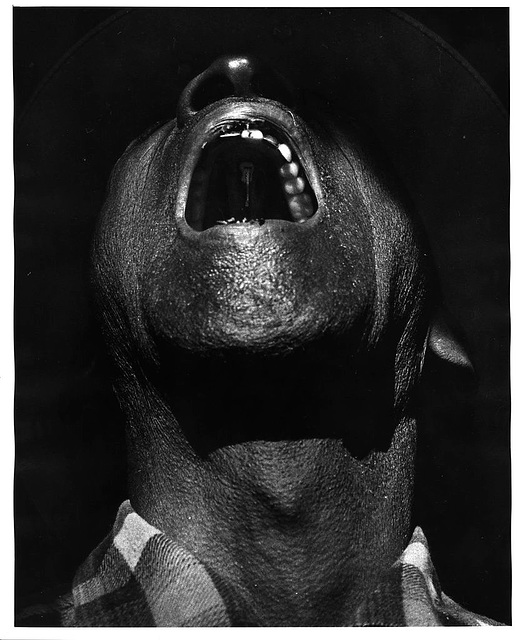

Texas blues singer Mance Lipscomb at the 1970 Beloit Blues Festival showing off a guitar illustration drawn onto his upper dentures.

Bodyglin (or Bowdie Glenn) Lipscomb was born in Navasota, Texas, northwest of Houston, on April 9, 1895. His father had been a slave in Alabama, and he acquired the name Lipscomb when he was sold to a Texas family of that name. Lipscomb took the nickname Mance to honor a friend named Emancipation who had died. Music ran in Lipscomb's family, and after his mother bought him a guitar when he was 11, he began accompanying his fiddler father at local dances. Before long, Lipscomb was in demand for "Saturday Night Suppers" in and around Grimes County, Texas.

In addition to his family, Lipscomb picked up musical pointers from Texas blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson. A traveling performer asked Lipscomb to go on tour in 1922, but Lipscomb said no, and until the 1960s he rarely left the area in which he was born. He married his wife Elnora around 1913 and the two stayed married for the rest of Lipscomb's life, raising one son, Mance Jr., three adopted children, and numerous grandchildren. He worked as a tenant farmer (he disliked the term "sharecropper") for various employers, and most of his musical appearances were at local functions. In contrast to the stereotype of the hard-living blues musician, he never gambled and rarely used alcohol.

Lipscomb did leave the Navasota area occasionally. He is known to have met Texas blues guitarist Sam "Lightnin'" Hopkins in Galveston in 1938. In 1956 Lipscomb hit a foreman who had mistreated his wife and mother; he had to leave town quickly and worked for several years in Houston, playing in bars and working in a lumberyard. The incident occurred on the farm of Tom Moore, and Lipscomb later recorded a ballad about the harsh conditions there, "Tom Moore's Farm." It was released anonymously, for Lipscomb's own protection. In A Well-Spent Life, a documentary about Lipscomb made by filmmaker Les Blank, the musician characterized the attitude of white farm owners this way: "Mule die, they buy another one; nigger die, they hire another one."

Things finally simmered down, and Lipscomb, with money saved from his work in Houston, bought land and built a house in Navasota. He got a job with a highway construction company, and one day in 1960 encountered music researchers Chris Strachwitz and Mack McCormick on a job site. They were looking for "Lightnin'" Hopkins, who had just left the area, but they agreed to listen to Lipscomb's music instead. Strachwitz was in the process of forming his California-based record company, Arhoolie, and a group of songs recorded around Lipscomb's kitchen table were put together on the album Mance Lipscomb: Texas Songster and Sharecropper, Arhoolie's debut release.

Lipscomb's name quickly became well known among blues and folk music fans. He appeared at the Texas Heritage Festival in Houston in 1960 and 1961, then capitalized on his California connection and made appearances for three years running (1961-63) at the large Berkeley Folk Festival held at the University of California. In between festival appearances he appeared at folk coffeehouses in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas, and he made several more recordings for Arhoolie.

What made Lipscomb stand out from the other Southern blues performers recorded during this period was the diversity of his repertory. His recordings provided examples of song and dance forms with both white and black roots--waltzes, two-steps, children's songs, jigs, reels, polkas, and a few others that Lipscomb named in his autobiography I Say Me for a Parable (the title meant "I give myself as an example"): the buzzard lope, cakewalk, slow drag, one-stop, wing-out, and ballin' the jack.

Many of these were African-American dance forms from early in the twentieth century, before the blues became popular among blacks and then turned into a nationwide craze. Perhaps Lipscomb's relative isolation in rural east Texas, far from the Mississippi River migration routes that shaped the blues, explained the preservation of these older forms in his music. For Lipscomb, the blues was only one type of music among many. It was a "true story song," he said in I Say Me for a Parable, "or nothin' but a cow huntin' for a calf.... Ya got ta be unsatisfied ta have the blues."

In the late 1960s, as interest in the blues mounted, Lipscomb experienced still greater success. He appeared at the Festival of American Folklife, held on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in 1968 and 1970, and he performed at other large festivals, including the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1970 and the Monterey Jazz Festival in California in 1973. Among the many musicians who became Lipscomb fans was vocalist Frank Sinatra, who issued a Lipscomb recording, Trouble in Mind, on his Reprise label in 1970. He appeared that year in Les Blank's film and two years later was featured in a French blues documentary, Out of the Blacks into the Blues.

Another fan was Texan-born Americana singer-songwriter Steve Earle, who was drawn to another aspect of Lipscomb's music: his intricate guitar work. In a No Depression article, Earle wrote that "as a finger-style guitarist, Mance had few peers (Mississippi John Hurt, Merle Watson, and Chet Atkins are the only names that come to mind), and any Lipscomb recording is a case study in how to get folks up out of their seats armed only with a single guitar.... The truth was, if you had Mance, you didn't need a band." Lipscomb preserved a sense of how individual entertainers managed to keep the attention of boisterous crowds of people at neighborhood functions.

Despite his success, Lipscomb avoided the trappings of luxury. He did, however, buy a set of dentures with a golden guitar stamped on the inside. Lipscomb suffered from heart trouble in the mid-1970s and gradually retired from the stage. I Say Me for a Parable was compiled by Texas author Glen Alyn from conversations with Lipscomb, which Lipscomb agreed to on condition that the two share any profits from the book equally. Alyn kept his end of the bargain, splitting the profits with Lipscomb's family after the musician's death in Navasota on January 30, 1976. I Say Me for a Parable, told entirely in Lipscomb's own voice and dialect without editing, later won a Music Book of the Year award from the ASCAP music licensing agency.

Sources: Archie Green Collection; Navasota's Native Son--Mance Lipscomb by Steve Earle

Bodyglin (or Bowdie Glenn) Lipscomb was born in Navasota, Texas, northwest of Houston, on April 9, 1895. His father had been a slave in Alabama, and he acquired the name Lipscomb when he was sold to a Texas family of that name. Lipscomb took the nickname Mance to honor a friend named Emancipation who had died. Music ran in Lipscomb's family, and after his mother bought him a guitar when he was 11, he began accompanying his fiddler father at local dances. Before long, Lipscomb was in demand for "Saturday Night Suppers" in and around Grimes County, Texas.

In addition to his family, Lipscomb picked up musical pointers from Texas blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson. A traveling performer asked Lipscomb to go on tour in 1922, but Lipscomb said no, and until the 1960s he rarely left the area in which he was born. He married his wife Elnora around 1913 and the two stayed married for the rest of Lipscomb's life, raising one son, Mance Jr., three adopted children, and numerous grandchildren. He worked as a tenant farmer (he disliked the term "sharecropper") for various employers, and most of his musical appearances were at local functions. In contrast to the stereotype of the hard-living blues musician, he never gambled and rarely used alcohol.

Lipscomb did leave the Navasota area occasionally. He is known to have met Texas blues guitarist Sam "Lightnin'" Hopkins in Galveston in 1938. In 1956 Lipscomb hit a foreman who had mistreated his wife and mother; he had to leave town quickly and worked for several years in Houston, playing in bars and working in a lumberyard. The incident occurred on the farm of Tom Moore, and Lipscomb later recorded a ballad about the harsh conditions there, "Tom Moore's Farm." It was released anonymously, for Lipscomb's own protection. In A Well-Spent Life, a documentary about Lipscomb made by filmmaker Les Blank, the musician characterized the attitude of white farm owners this way: "Mule die, they buy another one; nigger die, they hire another one."

Things finally simmered down, and Lipscomb, with money saved from his work in Houston, bought land and built a house in Navasota. He got a job with a highway construction company, and one day in 1960 encountered music researchers Chris Strachwitz and Mack McCormick on a job site. They were looking for "Lightnin'" Hopkins, who had just left the area, but they agreed to listen to Lipscomb's music instead. Strachwitz was in the process of forming his California-based record company, Arhoolie, and a group of songs recorded around Lipscomb's kitchen table were put together on the album Mance Lipscomb: Texas Songster and Sharecropper, Arhoolie's debut release.

Lipscomb's name quickly became well known among blues and folk music fans. He appeared at the Texas Heritage Festival in Houston in 1960 and 1961, then capitalized on his California connection and made appearances for three years running (1961-63) at the large Berkeley Folk Festival held at the University of California. In between festival appearances he appeared at folk coffeehouses in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas, and he made several more recordings for Arhoolie.

What made Lipscomb stand out from the other Southern blues performers recorded during this period was the diversity of his repertory. His recordings provided examples of song and dance forms with both white and black roots--waltzes, two-steps, children's songs, jigs, reels, polkas, and a few others that Lipscomb named in his autobiography I Say Me for a Parable (the title meant "I give myself as an example"): the buzzard lope, cakewalk, slow drag, one-stop, wing-out, and ballin' the jack.

Many of these were African-American dance forms from early in the twentieth century, before the blues became popular among blacks and then turned into a nationwide craze. Perhaps Lipscomb's relative isolation in rural east Texas, far from the Mississippi River migration routes that shaped the blues, explained the preservation of these older forms in his music. For Lipscomb, the blues was only one type of music among many. It was a "true story song," he said in I Say Me for a Parable, "or nothin' but a cow huntin' for a calf.... Ya got ta be unsatisfied ta have the blues."

In the late 1960s, as interest in the blues mounted, Lipscomb experienced still greater success. He appeared at the Festival of American Folklife, held on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in 1968 and 1970, and he performed at other large festivals, including the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1970 and the Monterey Jazz Festival in California in 1973. Among the many musicians who became Lipscomb fans was vocalist Frank Sinatra, who issued a Lipscomb recording, Trouble in Mind, on his Reprise label in 1970. He appeared that year in Les Blank's film and two years later was featured in a French blues documentary, Out of the Blacks into the Blues.

Another fan was Texan-born Americana singer-songwriter Steve Earle, who was drawn to another aspect of Lipscomb's music: his intricate guitar work. In a No Depression article, Earle wrote that "as a finger-style guitarist, Mance had few peers (Mississippi John Hurt, Merle Watson, and Chet Atkins are the only names that come to mind), and any Lipscomb recording is a case study in how to get folks up out of their seats armed only with a single guitar.... The truth was, if you had Mance, you didn't need a band." Lipscomb preserved a sense of how individual entertainers managed to keep the attention of boisterous crowds of people at neighborhood functions.

Despite his success, Lipscomb avoided the trappings of luxury. He did, however, buy a set of dentures with a golden guitar stamped on the inside. Lipscomb suffered from heart trouble in the mid-1970s and gradually retired from the stage. I Say Me for a Parable was compiled by Texas author Glen Alyn from conversations with Lipscomb, which Lipscomb agreed to on condition that the two share any profits from the book equally. Alyn kept his end of the bargain, splitting the profits with Lipscomb's family after the musician's death in Navasota on January 30, 1976. I Say Me for a Parable, told entirely in Lipscomb's own voice and dialect without editing, later won a Music Book of the Year award from the ASCAP music licensing agency.

Sources: Archie Green Collection; Navasota's Native Son--Mance Lipscomb by Steve Earle

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter