Garnet High School Basketball Team

An Invaluable Lesson Outside the Classroom

Undeterred

Spelman Grads Class of 1892

Garnet High School Students

Vivian Malone-Jones

A Revolutionary Hero: Agrippa Hull

First Draftee of WWI: Leo A. Pinckney

Private Redder

The Murder of Henry Marrow

David Fagen

1st Lt. John W. Madison's Family

Isreal Crump, Sr.

Early American Entertainment

Napolean Bonaparte Marshall

Captain Laurence Dickson

A Tragic and Hellish Life: Private Herman Perry

Captain Jamison

George Roberts

Lt. Robert W Diez

24th Infantry Regiment Korea

Pvt. George Watson

The Return

Graduates of Oberlin

Julie Hayden

Tennessee Town Kindergarten

One Little Girl

Edith Irby Jones

McIntire's Childrens Home Baseball Team

Bertha Josephine Blue

Give Me An 'A'!

We Finish to Begin

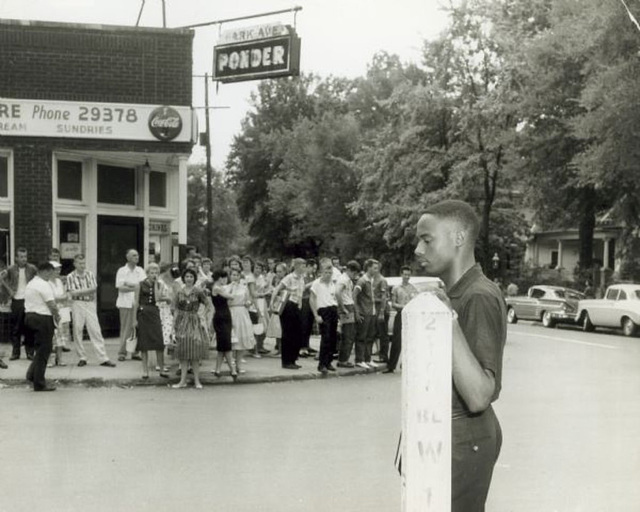

Standing Tall Amid the Glares

Segregated to the Anteroom

The 1st by 17 Years: The Story of Harry S. Murphy,…

Pedro Tovookan Parris

Enslaved No More: Wallace Turnage

Alvin Coffey

John Roy Lynch

A Loving Daughter: Nellie Arnold Plummer

Picking Cotton on Alex Knox's Plantation

From Slavery to Freedom to Prosperity

The Cazenovia Anti-Fugitive Slave Act Convention,…

Mr. and Mrs. Henson

"We Are Literally Slaves" An Early 20th Century B…

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

14 visits

A Solitary Figure

Original caption under photo: Jefferson Thomas of the Little Rock Nine is harassed by Central High School students as he waits for transportation after the first day of school.

Jefferson Thomas, (1942-2010), one of the "Little Rock Nine" who provoked a major civil rights battle when they integrated Arkansas' largest public high school in 1957 over the opposition of Gov. Orval E. Faubus, died September 5, 2010 at a care facility in Columbus, Ohio.

Mr. Thomas, who was 67, had pancreatic cancer. His death was confirmed by Carlotta Walls LaNier, who also enrolled at Central High School in 1957 and is president of the Little Rock Nine Foundation.

Many school districts in the South defied the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that declared racial segregation unconstitutional, forcing lawsuits and violent methods of enforcement. One of the first and most shocking showdowns occurred in Little Rock, when Faubus ordered the state's National Guard to keep black students out of Central High in September 1957.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent the Army's 101st Airborne Division to carry out the court's mandate. Nine black students were caught in the middle -- corralled by a spitting and rock-throwing mob of white protesters.

Taylor Branch, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the civil rights movement, once described Central High's integration as the "first on-site news extravaganza of the modern television era," and the subsequent images of the confrontation shocked millions for their disturbing look at American race relations.

Mr. Thomas said decades later that he was stunned and traumatized by the violence. He said Little Rock neighborhoods had not been segregated, even if the schools were, and he often practiced football on weekends with white kids from Central High before the conflict over integration.

"I had no reason to think that the quiet, peaceful place where I grew up could change so drastically," he told the Los Angeles Times. "I used to go to Central on weekends and play ball with the kids there."

Mr. Thomas, who lived a mile from Central High and three miles from the all-black high school, was a 15-year-old sophomore and track standout when he volunteered to break the color barrier at Central.

More than 100 black students volunteered, but the list was pared down by school officials. Only nine showed up on Sept. 4, 1957, to go to school, but they were denied entry by the Arkansas National Guard. They entered successfully on Sept. 25, escorted by the 101st Airborne.

Besides LaNier, the others were Minnijean Brown Trickey, Elizabeth Eckford, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed Wair, Terrence Roberts, Melba Pattillo Beals and Ernest Green.

The superintendent of schools counseled the teenagers not to retaliate against white protesters as the war between federal and state authority was captured on television. Once attending school, many of the nine were harassed and intimidated for months and years to come.

Brown Trickey was expelled after dumping a bowl of chili over the head of a white student who had insulted her; Mr. Thomas, Green and LaNier were the only ones of the Nine to graduate from Central, although all of them went on to college and careers.

Mr. Thomas said he tried whenever possible to avoid drawing attention.

"I would get out of the way," he told the Times. "I was a skinny little guy. I'd been on the track team in junior high. I could run fast. I looked at it this way: If I'd been in an all-black school and a 6-foot-1, 200-pound guy pushed me around, I wouldn't go flying into his chest. Mentally what would hurt was when little puny guys came up and slapped you in the face. You couldn't hit back.

"We got better experienced at getting out of the way as the year went on. You'd laugh at the fact that they ran into the wall while they were going after you."

Jefferson Allison Thomas, the youngest of seven children, was born Sept. 19, 1942, in Little Rock.

He said his role in the integration of Central High "destroyed the family base," noting that his father was fired from a sales job with International Harvester because of the controversy. The elder Thomas scraped by as a handyman and, the day after his son's graduation, moved to the family out of the state.

Jefferson Thomas later recalled his family's journey to California as a scene of misery from the pages of John Steinbeck's Depression-era novel "The Grapes of Wrath" -- "everything on top of the car and you move off."

He received a degree in business administration from what became California State University at Los Angeles and then served in the Army in Vietnam. He later worked in accounting for Mobil Oil and the Defense Department, from which he retired several years ago.

In 1964, he narrated "Nine From Little Rock," the Academy Award-winning documentary short directed by Charles Guggenheim that explored the incident through Mr. Thomas's eyes.

Survivors include his wife, Mary Branch Thomas of Groveport, Ohio, whom he married in 1998; a son from his first marriage, Jefferson Thomas Jr. of Los Angeles; two stepchildren, Frank Harper of Pittsburgh and Marilyn Carter of Columbus; three brothers; three sisters; a granddaughter; and a great-granddaughter.

On the 40th anniversary of their enrollment, members of the Little Rock Nine received Congressional Gold Medals, the highest award bestowed by Congress. They were presented by President Bill Clinton in a White House ceremony.

At a commemoration held near the 50th anniversary of Central High's integration, Mr. Thomas tried to bring levity to an otherwise somber occasion. Although discouraged from participating in athletics, he recalled attending a pep rally at the school and cheering along with white students, whom he thought were singing the school fight song and the state flag.

LaNier glared at him, he said. He then realized the problem: "That was not the fight song. That was not the Arkansas flag. They'd come in singing 'Dixie' and waving the Confederate flag."

Sources: Washington Post article by Adam Bernstein; Corbis

United Press International New Pictures

Jefferson Thomas, (1942-2010), one of the "Little Rock Nine" who provoked a major civil rights battle when they integrated Arkansas' largest public high school in 1957 over the opposition of Gov. Orval E. Faubus, died September 5, 2010 at a care facility in Columbus, Ohio.

Mr. Thomas, who was 67, had pancreatic cancer. His death was confirmed by Carlotta Walls LaNier, who also enrolled at Central High School in 1957 and is president of the Little Rock Nine Foundation.

Many school districts in the South defied the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that declared racial segregation unconstitutional, forcing lawsuits and violent methods of enforcement. One of the first and most shocking showdowns occurred in Little Rock, when Faubus ordered the state's National Guard to keep black students out of Central High in September 1957.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent the Army's 101st Airborne Division to carry out the court's mandate. Nine black students were caught in the middle -- corralled by a spitting and rock-throwing mob of white protesters.

Taylor Branch, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the civil rights movement, once described Central High's integration as the "first on-site news extravaganza of the modern television era," and the subsequent images of the confrontation shocked millions for their disturbing look at American race relations.

Mr. Thomas said decades later that he was stunned and traumatized by the violence. He said Little Rock neighborhoods had not been segregated, even if the schools were, and he often practiced football on weekends with white kids from Central High before the conflict over integration.

"I had no reason to think that the quiet, peaceful place where I grew up could change so drastically," he told the Los Angeles Times. "I used to go to Central on weekends and play ball with the kids there."

Mr. Thomas, who lived a mile from Central High and three miles from the all-black high school, was a 15-year-old sophomore and track standout when he volunteered to break the color barrier at Central.

More than 100 black students volunteered, but the list was pared down by school officials. Only nine showed up on Sept. 4, 1957, to go to school, but they were denied entry by the Arkansas National Guard. They entered successfully on Sept. 25, escorted by the 101st Airborne.

Besides LaNier, the others were Minnijean Brown Trickey, Elizabeth Eckford, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed Wair, Terrence Roberts, Melba Pattillo Beals and Ernest Green.

The superintendent of schools counseled the teenagers not to retaliate against white protesters as the war between federal and state authority was captured on television. Once attending school, many of the nine were harassed and intimidated for months and years to come.

Brown Trickey was expelled after dumping a bowl of chili over the head of a white student who had insulted her; Mr. Thomas, Green and LaNier were the only ones of the Nine to graduate from Central, although all of them went on to college and careers.

Mr. Thomas said he tried whenever possible to avoid drawing attention.

"I would get out of the way," he told the Times. "I was a skinny little guy. I'd been on the track team in junior high. I could run fast. I looked at it this way: If I'd been in an all-black school and a 6-foot-1, 200-pound guy pushed me around, I wouldn't go flying into his chest. Mentally what would hurt was when little puny guys came up and slapped you in the face. You couldn't hit back.

"We got better experienced at getting out of the way as the year went on. You'd laugh at the fact that they ran into the wall while they were going after you."

Jefferson Allison Thomas, the youngest of seven children, was born Sept. 19, 1942, in Little Rock.

He said his role in the integration of Central High "destroyed the family base," noting that his father was fired from a sales job with International Harvester because of the controversy. The elder Thomas scraped by as a handyman and, the day after his son's graduation, moved to the family out of the state.

Jefferson Thomas later recalled his family's journey to California as a scene of misery from the pages of John Steinbeck's Depression-era novel "The Grapes of Wrath" -- "everything on top of the car and you move off."

He received a degree in business administration from what became California State University at Los Angeles and then served in the Army in Vietnam. He later worked in accounting for Mobil Oil and the Defense Department, from which he retired several years ago.

In 1964, he narrated "Nine From Little Rock," the Academy Award-winning documentary short directed by Charles Guggenheim that explored the incident through Mr. Thomas's eyes.

Survivors include his wife, Mary Branch Thomas of Groveport, Ohio, whom he married in 1998; a son from his first marriage, Jefferson Thomas Jr. of Los Angeles; two stepchildren, Frank Harper of Pittsburgh and Marilyn Carter of Columbus; three brothers; three sisters; a granddaughter; and a great-granddaughter.

On the 40th anniversary of their enrollment, members of the Little Rock Nine received Congressional Gold Medals, the highest award bestowed by Congress. They were presented by President Bill Clinton in a White House ceremony.

At a commemoration held near the 50th anniversary of Central High's integration, Mr. Thomas tried to bring levity to an otherwise somber occasion. Although discouraged from participating in athletics, he recalled attending a pep rally at the school and cheering along with white students, whom he thought were singing the school fight song and the state flag.

LaNier glared at him, he said. He then realized the problem: "That was not the fight song. That was not the Arkansas flag. They'd come in singing 'Dixie' and waving the Confederate flag."

Sources: Washington Post article by Adam Bernstein; Corbis

United Press International New Pictures

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter