Metropolitan Museum V

Folder: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art Set IV includes: Ancient Near East Islamic Art The Metropolitan Museum of Art, often referred to simply as The Met, is one of the world's largest and most important art museums. It is located on the eastern edge of Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The Met also maintains "The Cloisters", which features medieval art.The Met's permanent collection…

(read more)

Molded Bottle in the Form of a Mother & Child in t…

| |

|

Title: Molded Vessel in the Form of a Mother and Child

Date: 12th–13th century

Geography: Attributed to Iran

Medium: Stonepaste; molded, painted under transparent turquoise glaze

Dimensions: H. 8 1/16 in. (20.5 cm)

W. 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm)

D. 3 in. (7.6 cm)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Gift of J. Lionberger Davis, 1965

Accession Number: 65.194.2

This object in the shape of a woman cradling a baby belongs to a large assemblage of ceramic figurines, whose original purpose is enigmatic.

Its lower part was left devoid of the turquoise glaze probably to avoid sticking with other objects stacked in the kiln. One can see there the black pigment painted directly on the body. Despite it unrefined appearance, the painted decoration quite precisely defines the details of the figures, such as the woman’s headdress, braids, and cross-hatched breasts. The marks painted on her cheeks follow a Central Asian iconography and are probably related to apotropaic rituals. They might represent tattoos or scars really practiced by women, as charms or applied as a form of facial adornment.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451809

Molded Bottle in the Form of a Mother & Child in t…

| |

|

Title: Molded Vessel in the Form of a Mother and Child

Date: 12th–13th century

Geography: Attributed to Iran

Medium: Stonepaste; molded, painted under transparent turquoise glaze

Dimensions: H. 8 1/16 in. (20.5 cm)

W. 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm)

D. 3 in. (7.6 cm)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Gift of J. Lionberger Davis, 1965

Accession Number: 65.194.2

This object in the shape of a woman cradling a baby belongs to a large assemblage of ceramic figurines, whose original purpose is enigmatic.

Its lower part was left devoid of the turquoise glaze probably to avoid sticking with other objects stacked in the kiln. One can see there the black pigment painted directly on the body. Despite it unrefined appearance, the painted decoration quite precisely defines the details of the figures, such as the woman’s headdress, braids, and cross-hatched breasts. The marks painted on her cheeks follow a Central Asian iconography and are probably related to apotropaic rituals. They might represent tattoos or scars really practiced by women, as charms or applied as a form of facial adornment.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451809

Human-Headed Winged Genie Relief in the Metropolit…

| |

|

Title: Relief panel

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 92 1/2 x 61 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (235 x 156.2 x 5.4 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1931

Accession Number: 31.72.1

This panel from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) depicts a winged supernatural figure. Such figures appear throughout the palace, sometimes flanking either the figure of the Assyrian king or a stylized "sacred tree." The reliefs were painted, but today almost none of the original pigment survives. This panel is a rare exception, with some paint clearly visible on the figure’s sandals. Where pigment has survived on reliefs, it has often been near the bases. One suggested explanation for this has been that after the fall of the Assyrian empire and the sacking of its palaces at the end of the seventh century B.C., these areas were immediately buried in debris, and thus afforded more protection from weathering than the rest of the reliefs.

The figure depicted on the panel is human-headed and faces left, holding in his left hand a bucket and in his right hand a cone whose exact nature is unclear. One suggestion has been that the gesture, sometimes performed as here by figures flanking a sacred tree, is symbolic of fertilization: the "cone" resembles the male date spathe used by Mesopotamian farmers, with water, to artificially fertilize female date-palm trees. It does seem likely that the cone was supposed to hold and dispense water from the bucket in this way, but it is described in Akkadian as a "purifier," and the fact that figures performing this gesture are also shown flanking the king suggests that some purifying or protective meaning is present. The figure wears a horned cap, indicating divinity, and jewelry: visible are a large pendant earring, a collar consisting of two bands of beads and spacers, a further collar with pendant tassel, armlets, and bracelets, on one of which can be seen a large central rosette symbol associated with divinity and perhaps particularly with the goddess Ishtar. Although we cannot know how these elements were originally painted, excavated parallels include elaborate jewelry in gold, inlaid with semi-precious stones. A collar or necklace such as that shown here might have been made up of semi-precious stones separated by gold spacer beads. The figure carries two knives, tucked into a belt with their handles visible at chest level.

The tree represents no real plant, and the form in which it is depicted varies within Neo-Assyrian art. The tree is generally thought to be a symbol of the agricultural fertility and abundance, and probably the more general prosperity, of Assyria. If this is so, then in protecting the tree and the king the winged figures of the Northwest Palace are all engaged in the protection of the Assyrian state.

The figures are supernatural but do not represent any of the great gods. Rather, they are part of the vast supernatural population that for ancient Mesopotamians animated every aspect of the world. They appear as either eagle-headed or human-headed and wear a horned crown to indicate divinity. Both types of figure usually have wings. Because of their resemblance to groups of figurines buried under doorways for protection whose identities are known through ritual texts, it has been suggested that the figures in the palace reliefs represent the apkallu, wise sages from the distant past. This may indeed be one level of their symbolism, but protective figures of this kind are likely to have held multiple meanings and mythological connections.

Figures such as these continued to be depicted in later Assyrian palaces, though less frequently. Only in the Northwest Palace do they form such a dominant feature of the relief program. Also unique to the Northwest Palace is the so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the middle of every relief, often cutting across the imagery. The inscription, carved in cuneiform script and written in the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, lists the achievements of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), the builder of the palace. After giving his ancestry and royal titles, the Standard Inscription describes Ashurnasirpal’s successful military campaigns to east and west and his building works at Nimrud, most importantly the construction of the palace itself. The inscription is thought to have had a magical function, contributing to the divine protection of the king and the palace.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322593

Human-Headed Winged Genie Relief in the Metropolit…

| |

|

Title: Relief panel

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 92 1/2 x 61 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (235 x 156.2 x 5.4 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1931

Accession Number: 31.72.1

This panel from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) depicts a winged supernatural figure. Such figures appear throughout the palace, sometimes flanking either the figure of the Assyrian king or a stylized "sacred tree." The reliefs were painted, but today almost none of the original pigment survives. This panel is a rare exception, with some paint clearly visible on the figure’s sandals. Where pigment has survived on reliefs, it has often been near the bases. One suggested explanation for this has been that after the fall of the Assyrian empire and the sacking of its palaces at the end of the seventh century B.C., these areas were immediately buried in debris, and thus afforded more protection from weathering than the rest of the reliefs.

The figure depicted on the panel is human-headed and faces left, holding in his left hand a bucket and in his right hand a cone whose exact nature is unclear. One suggestion has been that the gesture, sometimes performed as here by figures flanking a sacred tree, is symbolic of fertilization: the "cone" resembles the male date spathe used by Mesopotamian farmers, with water, to artificially fertilize female date-palm trees. It does seem likely that the cone was supposed to hold and dispense water from the bucket in this way, but it is described in Akkadian as a "purifier," and the fact that figures performing this gesture are also shown flanking the king suggests that some purifying or protective meaning is present. The figure wears a horned cap, indicating divinity, and jewelry: visible are a large pendant earring, a collar consisting of two bands of beads and spacers, a further collar with pendant tassel, armlets, and bracelets, on one of which can be seen a large central rosette symbol associated with divinity and perhaps particularly with the goddess Ishtar. Although we cannot know how these elements were originally painted, excavated parallels include elaborate jewelry in gold, inlaid with semi-precious stones. A collar or necklace such as that shown here might have been made up of semi-precious stones separated by gold spacer beads. The figure carries two knives, tucked into a belt with their handles visible at chest level.

The tree represents no real plant, and the form in which it is depicted varies within Neo-Assyrian art. The tree is generally thought to be a symbol of the agricultural fertility and abundance, and probably the more general prosperity, of Assyria. If this is so, then in protecting the tree and the king the winged figures of the Northwest Palace are all engaged in the protection of the Assyrian state.

The figures are supernatural but do not represent any of the great gods. Rather, they are part of the vast supernatural population that for ancient Mesopotamians animated every aspect of the world. They appear as either eagle-headed or human-headed and wear a horned crown to indicate divinity. Both types of figure usually have wings. Because of their resemblance to groups of figurines buried under doorways for protection whose identities are known through ritual texts, it has been suggested that the figures in the palace reliefs represent the apkallu, wise sages from the distant past. This may indeed be one level of their symbolism, but protective figures of this kind are likely to have held multiple meanings and mythological connections.

Figures such as these continued to be depicted in later Assyrian palaces, though less frequently. Only in the Northwest Palace do they form such a dominant feature of the relief program. Also unique to the Northwest Palace is the so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the middle of every relief, often cutting across the imagery. The inscription, carved in cuneiform script and written in the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, lists the achievements of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), the builder of the palace. After giving his ancestry and royal titles, the Standard Inscription describes Ashurnasirpal’s successful military campaigns to east and west and his building works at Nimrud, most importantly the construction of the palace itself. The inscription is thought to have had a magical function, contributing to the divine protection of the king and the palace.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322593

Molded Camel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, De…

| |

|

Title: Figurine in the Form of a Camel Carrying a Palanquin and Two Riders

Date: 12th–early 13th century

Geography: Attributed to probably Iran or Iraq

Medium: Stonepaste; molded in sections, glazed in turquoise

Dimensions: H. 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm)

W. 5 9/16 in. (14.1 cm)

D. 2 9/16 in. (6.5 cm)

Wt. 21.7 oz. (615.3 g)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Fletcher Fund, 1964

Accession Number: 64.59

Camel-rearing traditions may explain their frequent appearance in twelfth-century arts and their praise in mystical poetry. It has been suggested that Turkmen tribes bred hybrids of one- and two-humped camels and their southward migration and foundation of the Great Seljuq state was prompted, beyond an unstable political situation, by a climate change unfavorable to this occupation.

Molded Horse and Rider with a Cheetah in the Metro…

| |

|

Title: Mounted Hunter with Cheetah

Date: 12th–early 13th century

Geography: Attributed to Jazira (or Iran?)

Medium: Stonepaste; molded in sections, glazed in transparent turquoise, underglaze-painted in black

Dimensions: H. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm)

W. 3 in. (7.6 cm)

D. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm)

Wt. 24 oz (680.5 g)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1966

Accession Number: 66.23

Specialized cheetah-keepers tamed and trained cheetahs, caracals, and other wild felines for hunting expeditions, a traditional leisure pursuit of royalty and the wealthy elite. The trained felines rode with their masters on horses and hunted animals such as hares and gazelles. Despite this horseman’s weapons (a mace and a shield), his small cheetah suggests he is a hunter. The figurine was manufactured by altering a preexisting mold of a drinker: the applied arm holding the mace covers and conceals the mold’s original, bent arm holding a cup.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451850

Molded Horse and Rider with a Cheetah in the Metro…

| |

|

Title: Mounted Hunter with Cheetah

Date: 12th–early 13th century

Geography: Attributed to Jazira (or Iran?)

Medium: Stonepaste; molded in sections, glazed in transparent turquoise, underglaze-painted in black

Dimensions: H. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm)

W. 3 in. (7.6 cm)

D. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm)

Wt. 24 oz (680.5 g)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1966

Accession Number: 66.23

Specialized cheetah-keepers tamed and trained cheetahs, caracals, and other wild felines for hunting expeditions, a traditional leisure pursuit of royalty and the wealthy elite. The trained felines rode with their masters on horses and hunted animals such as hares and gazelles. Despite this horseman’s weapons (a mace and a shield), his small cheetah suggests he is a hunter. The figurine was manufactured by altering a preexisting mold of a drinker: the applied arm holding the mace covers and conceals the mold’s original, bent arm holding a cup.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451850

Molded Camel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, De…

| |

|

Title: Figurine in the Form of a Camel Carrying a Palanquin and Two Riders

Date: 12th–early 13th century

Geography: Attributed to probably Iran or Iraq

Medium: Stonepaste; molded in sections, glazed in turquoise

Dimensions: H. 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm)

W. 5 9/16 in. (14.1 cm)

D. 2 9/16 in. (6.5 cm)

Wt. 21.7 oz. (615.3 g)

Classification: Ceramics

Credit Line: Fletcher Fund, 1964

Accession Number: 64.59

Camel-rearing traditions may explain their frequent appearance in twelfth-century arts and their praise in mystical poetry. It has been suggested that Turkmen tribes bred hybrids of one- and two-humped camels and their southward migration and foundation of the Great Seljuq state was prompted, beyond an unstable political situation, by a climate change unfavorable to this occupation.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451741

Detail of the Assyrian Soldier Conducting Captives…

| |

|

Title: Relief fragment: Assyrian soldier conducting captives across the water

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 668–627 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nineveh

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 20 1/4 × 17 13/16 × 1 7/8 in., 48 lb. (51.5 × 45.3 × 4.8 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Accession Number: 32.143.5

This relief fragment comes from a palace at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in northern Iraq, and dates to the later years of the Assyrian empire, specifically the reign of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.). Originally part of a much larger scene, it shows one of the many small vignettes that characterized Assyrian depictions of military campaigns.

The relief shows a long, narrow reed boat, at the stern of which stands an Assyrian soldier. This bearded figure wears a conical helmet with cheek-guards, as well as greaves to protect his legs, but not body armor such as a cuirass; instead he wears the tunic and wrap commonly worn by most Assyrian men. On his back he carries a quiver for arrows, and though here no bow is visible, other reliefs show that this was also worn on the back. In his left hand he holds a long spear, which the sculptor has depicted as unnaturally passing behind his right arm in order to show both arms as complete. In his right hand the soldier holds a shorter stick, which he apparently uses to direct the much smaller figure propelling the boat with a pole. This figure, also male and bearded, has the dress and hairstyle normally associated in Assyrian art with Elam, a state in southwestern Iran against whom Ashurbanipal fought several wars, and helps to establish the probable location depicted: marshlands also existed in neighboring southern Iraq, but probably the area depicted here is within Elamite territory. The other two figures in the boat are women, both also probably Elamite. They sit on bundles, possibly cushions filled with dry plant matter, though they might instead be bags containing their belongings. Both make a distinctive gesture, raising both open hands with palms toward the face. Seen in several depictions of seated captives, it seems intended to show the sorrow and despair of prisoners.

In the lower part of the panel, the pole used to propel the boat appears to hit a dead body in the water. Assyrian campaign reliefs are unflinching in their depiction of the enemy dead. Assyrian soldiers, by contrast, are never shown being harmed. This absence is more than simple imperial bombast: in the ancient Near East the creation of images was commonly understood to hold real supernatural power. If depicting victory and enemy losses reinforced the empire’s power, so depicting Assyrian deaths might risk bringing them about. Assyrian campaign reliefs thus always show total Assyrian dominance. In reality, the marshes were an area where that dominance, based on superiority in open battle and expertise in siege warfare, was largely lost as the Assyrian army was forced to fight elusive enemies in a difficult and unfamiliar environment.

The background of the fragment shows only swirling water, but the boat confirms that the scene is set in marshlands. Small, slender and maneuverable, boats of this kind are ideal for use in the channels running through the marshes, and their reed construction is carefully shown in the depictions by Assyrian artists, to whom they were foreign. The technology has survived, and boats of the same kind are still used in the marshes of southern Iraq today.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322612

Assyrian Soldier Conducting Captives over the Wate…

| |

|

Title: Relief fragment: Assyrian soldier conducting captives across the water

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 668–627 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nineveh

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 20 1/4 × 17 13/16 × 1 7/8 in., 48 lb. (51.5 × 45.3 × 4.8 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Accession Number: 32.143.5

This relief fragment comes from a palace at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in northern Iraq, and dates to the later years of the Assyrian empire, specifically the reign of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.). Originally part of a much larger scene, it shows one of the many small vignettes that characterized Assyrian depictions of military campaigns.

The relief shows a long, narrow reed boat, at the stern of which stands an Assyrian soldier. This bearded figure wears a conical helmet with cheek-guards, as well as greaves to protect his legs, but not body armor such as a cuirass; instead he wears the tunic and wrap commonly worn by most Assyrian men. On his back he carries a quiver for arrows, and though here no bow is visible, other reliefs show that this was also worn on the back. In his left hand he holds a long spear, which the sculptor has depicted as unnaturally passing behind his right arm in order to show both arms as complete. In his right hand the soldier holds a shorter stick, which he apparently uses to direct the much smaller figure propelling the boat with a pole. This figure, also male and bearded, has the dress and hairstyle normally associated in Assyrian art with Elam, a state in southwestern Iran against whom Ashurbanipal fought several wars, and helps to establish the probable location depicted: marshlands also existed in neighboring southern Iraq, but probably the area depicted here is within Elamite territory. The other two figures in the boat are women, both also probably Elamite. They sit on bundles, possibly cushions filled with dry plant matter, though they might instead be bags containing their belongings. Both make a distinctive gesture, raising both open hands with palms toward the face. Seen in several depictions of seated captives, it seems intended to show the sorrow and despair of prisoners.

In the lower part of the panel, the pole used to propel the boat appears to hit a dead body in the water. Assyrian campaign reliefs are unflinching in their depiction of the enemy dead. Assyrian soldiers, by contrast, are never shown being harmed. This absence is more than simple imperial bombast: in the ancient Near East the creation of images was commonly understood to hold real supernatural power. If depicting victory and enemy losses reinforced the empire’s power, so depicting Assyrian deaths might risk bringing them about. Assyrian campaign reliefs thus always show total Assyrian dominance. In reality, the marshes were an area where that dominance, based on superiority in open battle and expertise in siege warfare, was largely lost as the Assyrian army was forced to fight elusive enemies in a difficult and unfamiliar environment.

The background of the fragment shows only swirling water, but the boat confirms that the scene is set in marshlands. Small, slender and maneuverable, boats of this kind are ideal for use in the channels running through the marshes, and their reed construction is carefully shown in the depictions by Assyrian artists, to whom they were foreign. The technology has survived, and boats of the same kind are still used in the marshes of southern Iraq today.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322612

Panels of an Assyrian Writing Board in the Metropo…

| |

|

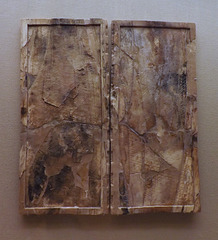

Title: Panels of a writing board

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 721–705 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Ivory

Dimensions: 13.19 x 6.3 x 0.59 in. (33.5 x 16 x 1.5 cm)

Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1954

Accession Number: 54.117.12a, b

Recovered from a well in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, where they had likely been thrown during the sack of the palace in 612 B.C., these two large flat pieces of ivory were used as writing boards. Ridges along one of the long sides of each board mark the attachment points for the hinges that held two or more leaves together. When closed, the smooth outer faces resemble the covers of a book. On the inner sides, a raised edge borders a writing surface cut into the board and roughened with cross-hatched scratches. This surface was filled with beeswax, and the scratches allowed the wax to adhere more securely to the smooth ivory. A scribe could then use a pointed stylus to make marks in the wax. Although most texts known from the ancient Near East were written on clay tablets, ivory or wooden writing boards with wax surfaces may have been more common than the limited archaeological finds would suggest. The earliest examples known come from the Uluburun shipwreck, a vessel wrecked off the southwest coast of Turkey around 1300 B.C. These two writing boards were made of wood and perhaps used to keep track of the ship’s cargo, like a modern shipping manifest. Writing boards are also shown in Assyrian reliefs, where a pair of scribes is shown in the aftermath of a battle, possibly recording important details such as enemy casualties or drawing up lists of booty (see Assyria to Iberia, p. 49, fig. 1.18). As the examples in the Metropolitan’s collection are ivory, they have survived better than wooden boards, which disintegrate in the soil of Mesopotamia. A total of 16 ivory writing boards were found in the same well in the Northwest Palace, along with some wooden examples. The ivory boards were all the same size and had been originally joined together by hinges, now missing. An outer cover leaf was found with an inscription identifying the series: "Palace of Sargon, king of the world, king of Assyria. He caused Enuma Anu Enlil to be inscribed on an ivory tablet and set it in his palace at Dur-Sharrukin."

Enuma Anu Enlil is the name of an important list of astrological omens. This inscription allowed scholars to date the boards to the reign of Sargon II, ca. 721-705 B.C. By this time, the Northwest Palace was largely used for storage, as Sargon was constructing a new capital city at Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad). It seems that the ivory writing boards intended for the king never arrived at the new royal palace, and instead were kept at Nimrud for unknown reasons.

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/324332

Detail of a Prayer Book with Images in Ghubar Scri…

| |

|

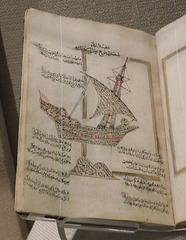

Title: Prayer Book

Calligrapher: 'Abd al-Qadir Hisari (Turkish)

Date: dated 1180 AH/1766 CE

Geography: Made in Turkey

Medium: Manuscript: ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Binding: leather and gold

Dimensions: H. 6 in. (15.2 cm)

W. 4 in. (10.2 cm)

Classification: Codices

Credit Line: Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2014

Accession Number: 2014.44

This small prayer book, or du'anama, belongs to a corpus of illustrated devotional texts produced in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unlike most prayer books created at the time, this one contains twenty-nine drawings of traditional Islamic themes and subjects, which are outlined in gold and filled with prayers in ghubar naskh, an especially fine or "dust-like" variety of the naskh script. These include representations of the Ka'ba, the footprints (kadem) of the Prophet Muhammad, the Seal of Solomon, the bifurcated sword of 'Ali (zu'l fiqar), Noah's Ark, the lamp of the Prophet, the trumpet of the Archangel Israfil, and the cave from the story of the Seven Sleepers in the Qur'an, among others. The manuscript is signed and dated by the calligrapher, a prominent mid-eighteenth-century master known for his calligrams and pictorial calligraphic compositions, such as the galleon with inscriptions referring to the story of the Seven Sleepers also in the Metropolitan's collection (2003.241). It also contains collectors' stamps dating to the first half of the nineteenth century. The leather binding is decorated with stamped and gilded medallions within a simple border. Prayer manuals enjoyed wide popularity in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a time of political reform and religious revivalism. Used for individual prayer, they also served as mediational devices to protect, comfort, and heal their owners.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/629452

Prayer Book with Images in Ghubar Script in the Me…

| |

|

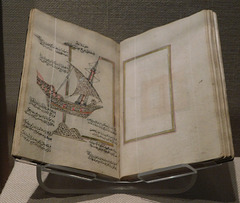

Title: Prayer Book

Calligrapher: 'Abd al-Qadir Hisari (Turkish)

Date: dated 1180 AH/1766 CE

Geography: Made in Turkey

Medium: Manuscript: ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Binding: leather and gold

Dimensions: H. 6 in. (15.2 cm)

W. 4 in. (10.2 cm)

Classification: Codices

Credit Line: Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2014

Accession Number: 2014.44

This small prayer book, or du'anama, belongs to a corpus of illustrated devotional texts produced in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unlike most prayer books created at the time, this one contains twenty-nine drawings of traditional Islamic themes and subjects, which are outlined in gold and filled with prayers in ghubar naskh, an especially fine or "dust-like" variety of the naskh script. These include representations of the Ka'ba, the footprints (kadem) of the Prophet Muhammad, the Seal of Solomon, the bifurcated sword of 'Ali (zu'l fiqar), Noah's Ark, the lamp of the Prophet, the trumpet of the Archangel Israfil, and the cave from the story of the Seven Sleepers in the Qur'an, among others. The manuscript is signed and dated by the calligrapher, a prominent mid-eighteenth-century master known for his calligrams and pictorial calligraphic compositions, such as the galleon with inscriptions referring to the story of the Seven Sleepers also in the Metropolitan's collection (2003.241). It also contains collectors' stamps dating to the first half of the nineteenth century. The leather binding is decorated with stamped and gilded medallions within a simple border. Prayer manuals enjoyed wide popularity in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a time of political reform and religious revivalism. Used for individual prayer, they also served as mediational devices to protect, comfort, and heal their owners.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/629452

Prayer Book with Images in Ghubar Script in the Me…

| |

|

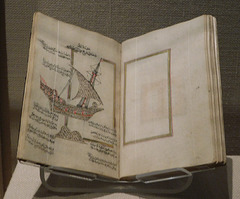

Title: Prayer Book

Calligrapher: 'Abd al-Qadir Hisari (Turkish)

Date: dated 1180 AH/1766 CE

Geography: Made in Turkey

Medium: Manuscript: ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Binding: leather and gold

Dimensions: H. 6 in. (15.2 cm)

W. 4 in. (10.2 cm)

Classification: Codices

Credit Line: Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2014

Accession Number: 2014.44

This small prayer book, or du'anama, belongs to a corpus of illustrated devotional texts produced in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unlike most prayer books created at the time, this one contains twenty-nine drawings of traditional Islamic themes and subjects, which are outlined in gold and filled with prayers in ghubar naskh, an especially fine or "dust-like" variety of the naskh script. These include representations of the Ka'ba, the footprints (kadem) of the Prophet Muhammad, the Seal of Solomon, the bifurcated sword of 'Ali (zu'l fiqar), Noah's Ark, the lamp of the Prophet, the trumpet of the Archangel Israfil, and the cave from the story of the Seven Sleepers in the Qur'an, among others. The manuscript is signed and dated by the calligrapher, a prominent mid-eighteenth-century master known for his calligrams and pictorial calligraphic compositions, such as the galleon with inscriptions referring to the story of the Seven Sleepers also in the Metropolitan's collection (2003.241). It also contains collectors' stamps dating to the first half of the nineteenth century. The leather binding is decorated with stamped and gilded medallions within a simple border. Prayer manuals enjoyed wide popularity in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a time of political reform and religious revivalism. Used for individual prayer, they also served as mediational devices to protect, comfort, and heal their owners.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/629452

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest items - Subscribe to the latest items added to this album

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter