MoMA

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is a preeminent art museum located in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, on 53rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. It is regarded as the leading museum of modern art in the world. Its collection includes works of architecture and design, drawings, painting, sculpture, photography, prints, illustrated books, film, and electronic media. MoMA's library and arc…

(read more)

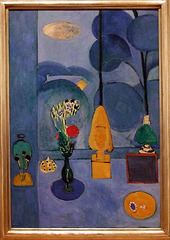

The Blue Window by Matisse in the Museum of Modern…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). The Blue Window. Issy-les-Moulineaux, summer 1913. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 35 5/8" (130.8 x 90.5 cm). Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79350

Goldfish and Palette by Matisse in the Museum of M…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). Goldfish and Palette. Paris, quai Saint-Michel, fall 1914. Oil on canvas, 57 3/4 x 44 1/4" (146.5 x 112.4 cm). Gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx.

Gallery label text

2006

Matisse described the abstract zone at the right of this composition as containing "a person who has a palette in his hand and who is observing." Most likely, it is the artist himself. The surrealist poet André Breton said of the painting, "I believe Matisse's genius is here . . . nowhere has Matisse put so much of himself as in this picture." While the work is indebted to the Cubist collages of Picasso, Matisse was convinced that Picasso was influenced by Goldfish and Palette when creating Harlequin, the following year.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Goldfish and Palette by Matisse in the Museum of M…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). Goldfish and Palette. Paris, quai Saint-Michel, fall 1914. Oil on canvas, 57 3/4 x 44 1/4" (146.5 x 112.4 cm). Gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx.

Gallery label text

2006

Matisse described the abstract zone at the right of this composition as containing "a person who has a palette in his hand and who is observing." Most likely, it is the artist himself. The surrealist poet André Breton said of the painting, "I believe Matisse's genius is here . . . nowhere has Matisse put so much of himself as in this picture." While the work is indebted to the Cubist collages of Picasso, Matisse was convinced that Picasso was influenced by Goldfish and Palette when creating Harlequin, the following year.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

The Piano Lesson by Matisse in the Museum of Moder…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). The Piano Lesson. Issy-les-Moulineaux, late summer 1916. Oil on canvas, 8' 1/2" x 6' 11 3/4" (245.1 x 212.7 cm). Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 75

The little boy playing the piano is Matisse's son Pierre. The woman who might be his teacher, apparently watching him from behind, is actually a figure in a painting, Matisse's Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal), which hangs on the wall by the window. Similarly the sensually posed nude at bottom left would be an unlikely class auditor were not this another artwork in Matisse's living room, his own bronze Decorative Figure.

Piano Lesson treats two unlike spaces—a view through a window into air and the flat and tangible canvas of Woman on a High Stool—as if they were quite equivalent. Matisse is addressing issues both formal and philosophical. In describing the playing of music he also takes art-making as his subject, and the filigree bar of curves supplied by the music stand and balcony ironwork—a lovely touch amid the painting's interlocking triangles and rectangles—might almost be a visual version of music's curling notes.

Those flat planes of muted color create a system of geometric compartments that link the painting to Cubism, whose radical inventions Matisse had observed over the preceding few years without ever committing himself to the style. Works like this one show him examining Cubist ideas about pictorial structure while also producing an image utterly personal to him.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Detail of the Piano Lesson by Matisse in the Museu…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). The Piano Lesson. Issy-les-Moulineaux, late summer 1916. Oil on canvas, 8' 1/2" x 6' 11 3/4" (245.1 x 212.7 cm). Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 75

The little boy playing the piano is Matisse's son Pierre. The woman who might be his teacher, apparently watching him from behind, is actually a figure in a painting, Matisse's Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal), which hangs on the wall by the window. Similarly the sensually posed nude at bottom left would be an unlikely class auditor were not this another artwork in Matisse's living room, his own bronze Decorative Figure.

Piano Lesson treats two unlike spaces—a view through a window into air and the flat and tangible canvas of Woman on a High Stool—as if they were quite equivalent. Matisse is addressing issues both formal and philosophical. In describing the playing of music he also takes art-making as his subject, and the filigree bar of curves supplied by the music stand and balcony ironwork—a lovely touch amid the painting's interlocking triangles and rectangles—might almost be a visual version of music's curling notes.

Those flat planes of muted color create a system of geometric compartments that link the painting to Cubism, whose radical inventions Matisse had observed over the preceding few years without ever committing himself to the style. Works like this one show him examining Cubist ideas about pictorial structure while also producing an image utterly personal to him.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Still Life after Jan Davidsz de Heem's Dessert by…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem's "La Desserte". Issy-les-Moulineaux, summer-fall 1915. Oil on canvas, 71 1/4" x 7' 3" (180.9 x 220.8 cm). Gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Detail of the Still Life after Jan Davidsz de Heem…

| |

|

Henri Matisse. (French, 1869-1954). Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem's "La Desserte". Issy-les-Moulineaux, summer-fall 1915. Oil on canvas, 71 1/4" x 7' 3" (180.9 x 220.8 cm). Gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Sculptures by Matisse in the Museum of Modern Art,…

| |

|

Henri Matisse

French, 1869-1954

From left to right:

Jeannette (I) early 1910

bronze

Jeannette (II) early 1910

bronze

Jeannette (III) spring 1910- fall 1911

bronze

Jeannette (IV) 1913

bronze

Jeannette (V) early 1916

bronze

Text from the MoMA label.

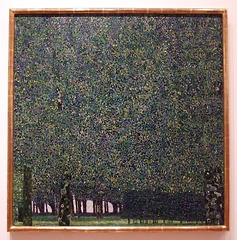

The Park by Klimt in the Museum of Modern Art, Dec…

| |

|

Gustav Klimt. (Austrian, 1862-1918). The Park. 1910 or earlier. Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 x 43 1/2" (110.4 x 110.4 cm). Gertrud A. Mellon Fund

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=78411

Hope II by Klimt in the Museum of Modern Art, Augu…

| |

|

Gustav Klimt. (Austrian, 1862-1918). Hope, II. 1907-08. Oil, gold, and platinum on canvas, 43 1/2 x 43 1/2" (110.5 x 110.5 cm). Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 54

A pregnant woman bows her head and closes her eyes, as if praying for the safety of her child. Peeping out from behind her stomach is a death's head, sign of the danger she faces. At her feet, three women with bowed heads raise their hands, presumably also in prayer—although their solemnity might also imply mourning, as if they foresaw the child's fate.

Why, then, the painting's title? Although Klimt himself called this work Vision, he had called an earlier, related painting of a pregnant woman Hope. By association with the earlier work, this one has become known as Hope, II. There is, however, a richness here to balance the women's gravity.

Klimt was among the many artists of his time who were inspired by sources not only within Europe but far beyond it. He lived in Vienna, a crossroads of East and West, and he drew on such sources as Byzantine art, Mycenean metalwork, Persian rugs and miniatures, the mosaics of the Ravenna churches, and Japanese screens. In this painting the woman's gold-patterned robe—drawn flat, as clothes are in Russian icons, although her skin is rounded and dimensional—has an extraordinary decorative beauty. Here, birth, death, and the sensuality of the living exist side by side suspended in equilibrium.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79792

Hope II by Klimt in the Museum of Modern Art, Augu…

| |

|

Gustav Klimt. (Austrian, 1862-1918). Hope, II. 1907-08. Oil, gold, and platinum on canvas, 43 1/2 x 43 1/2" (110.5 x 110.5 cm). Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 54

A pregnant woman bows her head and closes her eyes, as if praying for the safety of her child. Peeping out from behind her stomach is a death's head, sign of the danger she faces. At her feet, three women with bowed heads raise their hands, presumably also in prayer—although their solemnity might also imply mourning, as if they foresaw the child's fate.

Why, then, the painting's title? Although Klimt himself called this work Vision, he had called an earlier, related painting of a pregnant woman Hope. By association with the earlier work, this one has become known as Hope, II. There is, however, a richness here to balance the women's gravity.

Klimt was among the many artists of his time who were inspired by sources not only within Europe but far beyond it. He lived in Vienna, a crossroads of East and West, and he drew on such sources as Byzantine art, Mycenean metalwork, Persian rugs and miniatures, the mosaics of the Ravenna churches, and Japanese screens. In this painting the woman's gold-patterned robe—drawn flat, as clothes are in Russian icons, although her skin is rounded and dimensional—has an extraordinary decorative beauty. Here, birth, death, and the sensuality of the living exist side by side suspended in equilibrium.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79792

Detail of Hope II by Klimt in the Museum of Modern…

| |

|

Gustav Klimt. (Austrian, 1862-1918). Hope, II. 1907-08. Oil, gold, and platinum on canvas, 43 1/2 x 43 1/2" (110.5 x 110.5 cm). Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 54

A pregnant woman bows her head and closes her eyes, as if praying for the safety of her child. Peeping out from behind her stomach is a death's head, sign of the danger she faces. At her feet, three women with bowed heads raise their hands, presumably also in prayer—although their solemnity might also imply mourning, as if they foresaw the child's fate.

Why, then, the painting's title? Although Klimt himself called this work Vision, he had called an earlier, related painting of a pregnant woman Hope. By association with the earlier work, this one has become known as Hope, II. There is, however, a richness here to balance the women's gravity.

Klimt was among the many artists of his time who were inspired by sources not only within Europe but far beyond it. He lived in Vienna, a crossroads of East and West, and he drew on such sources as Byzantine art, Mycenean metalwork, Persian rugs and miniatures, the mosaics of the Ravenna churches, and Japanese screens. In this painting the woman's gold-patterned robe—drawn flat, as clothes are in Russian icons, although her skin is rounded and dimensional—has an extraordinary decorative beauty. Here, birth, death, and the sensuality of the living exist side by side suspended in equilibrium.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79792

Detail of Hope II by Klimt in the Museum of Modern…

| |

|

Gustav Klimt. (Austrian, 1862-1918). Hope, II. 1907-08. Oil, gold, and platinum on canvas, 43 1/2 x 43 1/2" (110.5 x 110.5 cm). Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 54

A pregnant woman bows her head and closes her eyes, as if praying for the safety of her child. Peeping out from behind her stomach is a death's head, sign of the danger she faces. At her feet, three women with bowed heads raise their hands, presumably also in prayer—although their solemnity might also imply mourning, as if they foresaw the child's fate.

Why, then, the painting's title? Although Klimt himself called this work Vision, he had called an earlier, related painting of a pregnant woman Hope. By association with the earlier work, this one has become known as Hope, II. There is, however, a richness here to balance the women's gravity.

Klimt was among the many artists of his time who were inspired by sources not only within Europe but far beyond it. He lived in Vienna, a crossroads of East and West, and he drew on such sources as Byzantine art, Mycenean metalwork, Persian rugs and miniatures, the mosaics of the Ravenna churches, and Japanese screens. In this painting the woman's gold-patterned robe—drawn flat, as clothes are in Russian icons, although her skin is rounded and dimensional—has an extraordinary decorative beauty. Here, birth, death, and the sensuality of the living exist side by side suspended in equilibrium.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79792

Propellers by Leger in the Museum of Modern Art, J…

| |

|

Fernand Léger. (French, 1881-1955). Propellers. 1918. Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 25 3/4" (80.9 x 65.4 cm). Katherine S. Dreier Bequest.

Text from www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79039

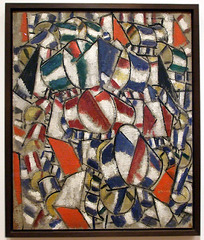

Contrast of Forms by Leger in the Museum of Modern…

| |

|

Fernand Léger. (French, 1881-1955). Contrast of Forms. 1913. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 32" (100.3 x 81.1 cm). The Philip L. Goodwin Collection.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=78788

Contrast of Forms by Leger in the Museum of Modern…

| |

|

Fernand Léger. (French, 1881-1955). Contrast of Forms. 1913. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 32" (100.3 x 81.1 cm). The Philip L. Goodwin Collection.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=78788

Three Women by Leger in the Museum of Modern Art,…

| |

|

Fernand Léger. (French, 1881-1955). Three Women. 1921. Oil on canvas, 6' 1/4" x 8' 3" (183.5 x 251.5 cm). Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

Gallery label text

2006

This painting represents a group of three reclining nudes drinking tea or coffee in a chic apartment. While the reclining nude is a common subject in art history, these women’s bodies have been simplified into rounded and dislocated forms, their skin not soft but firm, buffed, and polished. The machinelike precision and solidity with which Léger renders human form relates to his faith in modern industry and to his hope that art and the machine age would together reverse the chaos unleashed by World War I.

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 100

In Three Women, Léger translates a common theme in art history—the reclining nude—into a modern idiom, simplifying the female figure into a mass of rounded and somewhat dislocated forms, the skin not soft but firm, even unyielding. The machinelike precision and solidity that Léger gives his women's bodies relate to his faith in modern industry, and to his hope that art and the machine age would together remake the world. The painting's geometric equilibrium, its black bands and panels of white, suggest his awareness of Mondrian, an artist then becoming popular. Another stylistic trait is the return to variants of classicism, which was widespread in French art after the chaos of World War I. Though buffed and polished, the simplified volumes of Lger's figures are, nonetheless, in the tradition of classicists of the previous century.

A group of naked women taking tea, or coffee, together may also recall paintings of harem scenes, for example, by Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres, although there the drink might be wine. Updating the repast, Léger also updates the setting—a chic apartment, decorated with fashionable vibrancy. And the women, with their flat-ironed hair hanging to one side, have a Hollywood glamour. The painting is like a beautiful engine, its parts meshing smoothly and in harmony.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Three Women by Leger in the Museum of Modern Art,…

| |

|

Fernand Léger. (French, 1881-1955). Three Women. 1921. Oil on canvas, 6' 1/4" x 8' 3" (183.5 x 251.5 cm). Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

Gallery label text

2006

This painting represents a group of three reclining nudes drinking tea or coffee in a chic apartment. While the reclining nude is a common subject in art history, these women’s bodies have been simplified into rounded and dislocated forms, their skin not soft but firm, buffed, and polished. The machinelike precision and solidity with which Léger renders human form relates to his faith in modern industry and to his hope that art and the machine age would together reverse the chaos unleashed by World War I.

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 100

In Three Women, Léger translates a common theme in art history—the reclining nude—into a modern idiom, simplifying the female figure into a mass of rounded and somewhat dislocated forms, the skin not soft but firm, even unyielding. The machinelike precision and solidity that Léger gives his women's bodies relate to his faith in modern industry, and to his hope that art and the machine age would together remake the world. The painting's geometric equilibrium, its black bands and panels of white, suggest his awareness of Mondrian, an artist then becoming popular. Another stylistic trait is the return to variants of classicism, which was widespread in French art after the chaos of World War I. Though buffed and polished, the simplified volumes of Lger's figures are, nonetheless, in the tradition of classicists of the previous century.

A group of naked women taking tea, or coffee, together may also recall paintings of harem scenes, for example, by Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres, although there the drink might be wine. Updating the repast, Léger also updates the setting—a chic apartment, decorated with fashionable vibrancy. And the women, with their flat-ironed hair hanging to one side, have a Hollywood glamour. The painting is like a beautiful engine, its parts meshing smoothly and in harmony.

Text from: www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O:AD:...

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest items - Subscribe to the latest items added to this album

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter