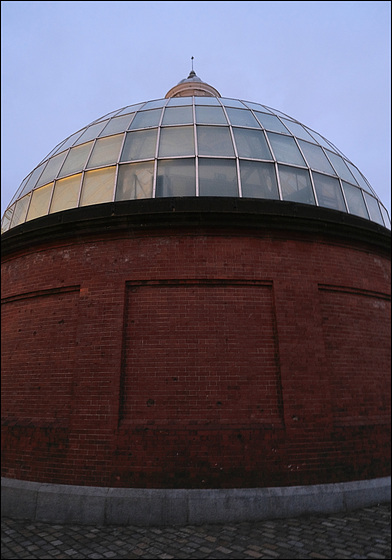

The Greenwich Foot Tunnel is no exception. My own first post mentions ‘tourist attraction’, ‘engineering marvel’, ‘iconic architectural features’, and these descriptive terms are all relevant and true, but I would like for my second instalment to mention those who are too often erased from memory when we celebrate our pasts.

A quick search of the history of the Greenwich foot tunnel will tell you that it was the brainchild of Sir Alexander Richardson Binnie (26 March 1839 – 18 May 1917), knighted in 1897 by Queen Victoria for services to engineering. and was elected President of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1905. You will find out that the boring of tunnels under the Thames benefited from the clever tunnel shield invented by engineer extraordinaire Marc I. Brunel. In fact, you’ll read a commemorative plaque, on both north and south entrance, to these men whose contribution has been deemed worth remembering, but try searching for the invisible ones, the ones who dug the earth, the ones who laid the bricks, or the tiles...

I was initially searching for some information about these labourers, half-expecting to find early pictures of mud-covered wiry men with thick moustaches and wide-eyed, a little in the style of what our collective unconscious now would associate with miners... I was not prepared for the punch-in-the-gut experience of reading about the history of the brick making-industry of the Victorian era. Much has been said of the conditions of the workers in the textile industry, of child labour in the mines, but I don’t think I have ever heard anything about brick-making... or maybe it's only because I never had to think about it.

And besides, doesn’t the same collective unconscious prefer to continue imagining these distant times as the beginning of the march of the civilised world towards our more enlightened times? The seed of ‘Progress’ - with a capital P - when the ruling classes conceded that it was time to ensure the people be given at least a half-decent chance? The Factory Acts, 1802, were a series of acts passed by the UK Parliament to bring in regulations aiming to improve the conditions of industrial employment. These regulated hours of work, seeking to ensure the moral welfare of young children employed in cotton mills. Even if it took until 1833 for a new Act to be passed, that established the Factory Inspectorate, before the earlier one was actually implemented, we so want to believe that it was the start of a new, fairer society. In 1844, in yet another Act, these regulations were extended to the employment of women. More Acts were passed, improving conditions, limiting working time to... ten-hour days; I guess it is all relative.

However, the brick-making industry remained unregulated, the new rules applying to manufacturing companies with more than 50 employees. Brickmakers were often family affairs, a job that was very seasonal - subject to shutting down operation if it rained, so it was important to produce as much as possible when the weather permitted. This meant everyone in the family had to join in, and when the weather was clement, it was necessary to work as many hours as possible.

In a House of Lords debate of 11th July 1871, Lord Shaftesbury explains his horror at reading about the conditions in the brickfields, of which apparently there were around 3,000 in England, employing as many as 30,000 children and young persons, ages varying from 3 ½ to 17, working 14 to 16 hours per day. George Smith, of Coalville, who had grown up working in the brickfields, described how he weighed an 8 year old child and found that ‘although he was somewhat over eight years of age, he weighed but 52½lb and was employed carrying 43lb weight of clay on his head an average distance of 15 miles daily, and worked 73 hours a week.’

Although I don’t know that the bricks used in the Greenwich foot tunnels came from kilns where children worked, one thing is for sure, I will no longer look at these red brick buildings in the same way. I have just ordered Peter Hounsell’s 'Bricks of Victorian London’ which should shed further light on the topic, and am really looking forward to reading it.

And while I was looking at various websites, I also came across this article from Al Jazeera describing the very similar conditions experienced by children working in brick kilns in Pakistan: The spiralling debt trapping Pakistan’s brick kiln workers and a harrowing three-part documentary available on the Pulitzer Centre website: ‘Bonded by Brick’.

Sign-in to write a comment.