DC of Old

This set is all about my beloved hometown, Washington, DC. It's people, places and events.

Center Market Vendor

Center Market (located at Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street, NW) was a hub of activity for the District of Columbia's African American population during the 1800s. Both free and enslaved African Americans bought and sold produce at the market and operated stalls before and after Emancipation. This unknown woman, photographed in 1890, ran her own stall, possibly the one just behind her. [Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division] [Info: Histories of the National Mall]

Once the largest commercial market in Washington, Center Market opened in 1801. The original buildings were replaced in 1872 by a building designed by German architect, Adolph Cluss. The market was close to the Washington City Canal, railroads, and streetcar lines. It was demolished in 1931 and is the current site of the National Archives. Vendors sold all manner of goods inside: produce, meat and fish, and staples. Because of its access to transportation, Center Market was able to sell goods that had been grown or produced far away.

--/--/----

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas

In 1864, the Battle of Fort Stevens began in Washington, D.C.'s Brightwood neighborhood. Elizabeth “Aunt Betty” Thomas, a free African American woman, owned a portion of the land where Union soldiers demolished her home to build their fort. At the site, Thomas spoke with President Lincoln, and beginning in 1924, the city has celebrated Lincoln-Thomas Day.

Aunt Betty told the story that as she sat weeping with her child, watching the soldiers dismantle her house, President Lincoln approached her and attempted to console her by saying "It is hard, but you shall reap a great reward." Aunt Betty was never compensated for the damages, but maintained that she was confident Lincoln would have made sure she was, had he survived. The above photograph dated November 7, 1911, shows Mrs. Thomas posed with Civil War veterans at the Lincoln Memorial Boulder at Fort Stevens, which commemorates the spot where the president was actually under enemy fire while visiting soldiers at the fort on July 11, 1864.

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas (1821-1917), was born in Prince George’s County, Maryland. As a child, Thomas and her parents moved to Vinegar Hill, a small community of free blacks located in northwest Washington, D.C., approximately two miles south of the Maryland border. The family settled on a high point beside the Seventh Street Turnpike, a major road leading to downtown Washington.

When the Civil War began, the Nation’s Capital was protected by a single fort: Fort Washington, located 12 miles south of the city along the Potomac River. Realizing the defense of the capital was dangerously inadequate following the Union defeat at Manassas in July 1861, Congress voted in favor of constructing a ring of forts and other defensive works to encircle the city. Soon afterwards, miles of trees were cleared and building commenced. By the end of the war, 68 forts, 93 batteries, 20 miles of rifle pits, and 32 miles of military roads surrounded the capital and Washington became the most heavily fortified city in the world.

The Thomas’ Seventh Street Turnpike property, then owned by Elizabeth and her siblings, was an ideal and necessary location for a fort. In September 1861, Union troops took possession of her land and ultimately destroyed her home, barn, orchard and garden to build Fort Massachusetts, later renamed Fort Stevens. According to Thomas, at the time her house was being demolished she was holding her six-month old baby and weeping beneath a sycamore tree. As soldiers removed her belongings, a tall, slender man dressed in black approached her and said, “It is hard, but you shall reap a great reward.” The man offering comfort was President Lincoln. Thomas’ encounter with the stranger was a story she told throughout her life. Whether or not he was President Lincoln, the tale further solidified Thomas’ role in the history of Fort Stevens.

In July 1864, Confederate troops under the leadership of General Jubal Early attempted to invade Washington. Fort Stevens and nearby Fort DeRussy led the defense of the capital as skirmishes broke out. President Lincoln, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln and members of the president’s cabinet traveled to Fort Stevens to observe the two-day battle. The president watched the fighting as Confederate sharpshooters fired upon the fort. President Lincoln became the second sitting president to come under enemy fire as Union forces successfully thwarted the invasion.

Following the Civil War, Elizabeth Thomas continued to reside near Fort Stevens. She remained the owner of portions of the fort, and during the course of her life, she amassed a considerable amount of land in the vicinity. At the turn of the century, Thomas sold some of her Fort Stevens acreage to an influential Washingtonian who hoped to preserve the remaining earthworks and establish a park.

In 1911, she joined veterans of the Battle of Fort Stevens for the dedication of a monument to President Lincoln located on the site where he observed the 1864 conflict. For many years, Elizabeth Thomas fought for compensation for the damage and loss of her property incurred during the war. She was eventually awarded $1,835 in 1916, a year before she died.

During the 1920s, the federal government acquired Fort Stevens and the site became a unit of the National Park Service in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps reconstructed a portion of the fort. Today, Fort Stevens is a neighborhood gathering place where the stories of the battle and Elizabeth Thomas continue to be told.

Sources: National Park Service, Elizabeth Proctor Thomas

Civil War Defenses of Washington, Rock Creek Park; Photographer, Willard R. Ross; Historical Society of Washington; Cowan's Auction

--/--/----

Odessa Madre: The 'Al Capone' of DC

Odessa Madre, one of the richest, most flamboyant, big-hearted hustlers who ever worked the shadier side of the Nation's Capitol, died penniless on March 6, 1990 at age 83.

"She was the Al Capone of Washington," said Paul Kenney, 65, one of a few old friends who attended her burial at the Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland. Kenny said that when he got out of jail in 1958 after serving more than 13 years for a robbery conviction, it was Madre who gave him a room and bought him new suits until he got on his feet. "She was always helping out people."

In the 1930s and '40s, she built an empire of joints that served liquor by the shot and bawdy houses. Her headquarters was Club Madre, 2204 14th St. NW. In those days, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and more black celebrities would appear.

A madame with a half-dozen bawdy houses and 20 ladies in her employ, she became so rich that her shopping sprees made headlines. She was also generous.

"She loaned a lot of needy people money, as well as provided contacts for gambling and drugs," Robert Lee, a former vice squad detective, told The Washington Post in 1980. "She knew practically every big-time gangster nationwide. She was what they call a counselor in the mob. She mediated disputes between blacks and whites, a referee. She kept a lot of people from getting hurt."

She had started at age 17, first swearing off men and calling herself a "black widow," then spinning a web of jill joints, bawdy houses and numbers banks that eventually passed for "organized crime," albeit in a down-home sort of way. She became the self-described Queen of Washington's Underworld.

Many police in Washington today who know the lowdown on the low-life in this town recall her. Perhaps no other person has seen so much of the District's narcotics, numbers and "tenderloin" trade and is still alive to tell about it.

According to one police affidavit filed in U.S. District Court in 1975, "She practices a resourceful and shrewd form of circumspection that has enabled her to survive and thrive in her illegal activities over the past 40 years."

The land where John Hechinger built his store in Northwest Washington had been named Madre Park after her grandfather, Moses Madre, Sr., a Civil War veteran. Only two local families had been so honored. Now she is the last of the Madres. Born in 1907, she was the only child of Annie T. Madre a seamstress, who kept her spiffily dressed, and Lindsay Montgomery Madre, a barber, who let her raid his till.

Her father's shop was located on 7th Street NW, next door to Uncle Madre's pool hall. She would inherit property and prosper as this strip blossomed to cultural significance during the 1940s and 1950s.

Madre attended Dunbar High School and graduated with honors in 1925. In those days, prominent black families around the country -- the "E-lites," as Madre called them -- tried to send their children away to Dunbar as though it were a college. Indeed, with more Ph.D.s on its faculty than any other U.S. high school, it was something of that. From Madre, a spectacular career, perhaps as a teacher, was expected.

Madre's aunt Marie Madre Marshall, was an educator and attorney --- who graduated from the old M Street High School, the forerunner to Dunbar. Her aunt had arranged for Odessa to attend Dunbar and for her to move into the fashionable LeDroit Park area with the aunt and her husband, a preacher. He helped tutor Madre in oratory and mathematics.

Her expertise at mathematics came in handy. She started out buying two five-gallon tins of whiskey a day and sold the liquor at 25 cents a jill (or shot). Within a matter of weeks, she was up to four five-gallon tins a day. In time the word was out that she was "in" with the cops.

"All the big shots were looking to do business with me," Odessa said proudly. "My protection would automatically be theirs, too. I said to myself, 'Let the good times roll.'"

By 1946, court records show, Madre was operating at least six bawdy houses scattered about Northeast and Northwest Washington. She recalled employing about 20 women at one time. She opened two jill joints in Shaw, and rented a room at 16th and U streets for a large bookmaking operation.

Her headquarters were located at 2204 14th St. NW, the Club Madre. The club offered liquor by the shot, numbers by the book and girls by the hour. The late comedienne Jackie "Moms" Mabley performed there free, spending her days in Washington as Odessa's guest. The two became like sisters.

On those special nights, say when Mabley and Count Basie would appear on the same bill and Joe Louis and Nat King Cole would be in the audience, Odessa would make her grand entrance into her club -- mink from ear to ankle. That was a lot of mink, because she weighed about 260 pounds back then. Reserved, in the center of the club, was a table vacant except for a dozen, long-stemmed roses. Odessa would lead an entourage -- a trail of about six or seven beautiful "yella gals," mostly all for sale, followed by a train of lusty, well-heeled "E-lite" gents.

Her shopping sprees were so extravagant they made newspaper headlines. One account, in the Washington Afro-American, reported that Madre had entered a store where blacks were not supposed to go. The salesgirl summoned the manager, then promptly fainted when Madre began pulling roll upon roll of hundred dollar bills from her purse, demanding to see the finest fur coat in the store.

At her peak, Madre's net income was estimated at more than $100,000. But she never really left the area, remaining within the protection of the policemen she had grown up with, and their sons.

"I never had any big trouble," she remembered. "Some guys would have their jill joints raided or muggers would break in and rob them, but people knew better than to mess with me."

Whenever she left her house, she usually traveled with a couple of bodyguards. They were often young men whom she had befriended on the street. "I would see somebody on the street that I liked and I'd give them a little something. They would usually be right friendly with me for a while."

She was also friendly with the destitute of the Shaw neighborhood. Small kids playing on the street near her house often would be rewarded with cash for "being good children." When the "boosters" -- shoplifters -- stopped by her house to sell their booty, she would sometimes put in a special order for children's clothes. When the boosters returned, she had the clothes wrapped and sent out as gifts.

"Odessa was basically forced into a life of crime," said Metropolitan Police Det. Robert Lee, who worked as an undercover vice squad officer during the 1960s. "There weren't hardly any jobs for black people like her when she was coming along . . . and once you got an arrest record, you could hang it up.

During World War II, horse racing -- on which the daily numbers games were based -- slowed down, partly because horses were in short supply (they were being eaten). So from her small upstairs office at 16th and U streets NW, Madre and Billy "Whitetop" Simpkins started a numbers bank, which became known as "The Night Number," complete with telephones and charts and a revolving cage.

She was throwing money about town for lavish clothes, trips and cars. She kept some money in the bank, but most was stashed in her house for wedding and divorce celebrations, bail bonds, gambling and for "ice," the term used for police protection.

"You say was it worth it? Child, you wonder does crime pay? I'll tell you, yes. It pays a helluva lot of money. And money is something. I don't care who you are, when you got money you can get a lot of doors open because there's always some larcenous heart who's gonna listen to you.

"And when you show 'em that money ...." her sagging face grew taut and her eyes shone bright ...."if you got a wad, honey, they'll suck up to ya like you was a Tootsie Roll."

When she died, they waited eight days for a family member to claim her body. Her best friends were able to raise only $51 for her funeral before W.H. Bacon of the Bacon Funeral Home on 14th Street NW said he decided to make sure she wouldn't be buried in a cheap welfare casket.

"She helped a lot of people. She deserved better. She gave me money to bury folks through the years," Bacon said.

At Madre's funeral, one of her friends, Flethelle Carnegie, sang a rendition of Frank Sinatra's "My Way" because "that was her. She did everything her way, what ever she did."

Sam Courtney, a photographer who said he had known Madre since 1939, said people looked up to her because she was rich and she had power. "She was a legend, she was."

Sources: Courtland Milloy, Washington Post Staff Writer (Sept. 28, 1980); Thomas Bell, Washington Post (March 8, 1990)

Painting by Dana Ellyn Odessa and her Yella Gals

www.danaellyn.com/12_14/odessa.jpg

--/--/----

Silent Witnesses

Anti-lynching protesters as they stood in silence in Washington DC. Each wearing the name of those who have been lynched in The Land of the Free and Home of the Brave .

Source: The Washington Post

21 July 1869

Headline: Acquittal of the Negress Minnie Gaines by a Mixed Race Jury, New York Times July 21, 1869

Twelve members (including the two alternates) of the Minnie Gaines Murder Trial.

The murder occurred on March 5, 1869

The summer of 1869, Minnie Gaines, an African American woman was charged with bludgeoning her white lover to death. Gaines was a freed woman originally from Fredericksburg, Virginia. Her lover, James Ingle, had been a watchman at the Department of Interior. Gaines's lawyers, former Ohio congressmen Albert G. Riddle and former Freedmen's Bureau lawyer Andrew K. Browne, were well known in Republican circles. Lawyers for both sides called some sixty witnesses, among them some of the capital's best known physicians. For more than a week in July, witnesses discussed slavery, sex, violence, and insanity, as rapt onlookers filled the courtroom.

The facts in the case were relatively straightforward. Gaines, who worked as a servant in a boardinghouse confronted Ingle and demanded that he support their unborn child, he refused and threatened several times to kill her. Desperate, Gaines came to Ingle's room with a pistol and attempted to shoot him. When the pistol malfunctioned, she picked up a hammer or an axe and beat him delivering a head wound that ultimately killed him. Gaines immediately turned herself in to police. In court, the question was whether Gaines would be convicted of premeditated murder, as the prosecutor wished, or of some lesser crime, such as murder or manslaughter, or whether she would be declared not guilty because of temporary insanity.

Besides the raw sensationalism of the trial, the public took great interest in the fact that Gaines was the capital's first murder defendant to be tried before a racially mixed jury. Newspaper reporters followed the jury avidly, and the jurors ... six black men and six white men seemed conscious of their place in history. The jurors publicly broke taboos of race and space. While sequestered, they took their meals together and were quartered together at a third class hotel. One Sunday, they held a private prayer meeting and, later in the afternoon, rode out into the country with the bailiffs on an omnibus. The men also had their picture taken at a photographer's studio.

Duke Anderson, the pastor at the church Gaines attended, "fears the colored jurors will not be likely to acquit Minnie Gaines and give plausible reasons for the same." By Anderson's reasoning, we might speculate that he worried that the black jurors would feel pressure to avoid the impression of undue leniency on an African American defendant.

Justice George Fisher's instructions to the jurors also reflected the political sensitivity of the jurors' mandate. After outlining the range of possible verdicts Fisher reminded them that they could not acquit Gaines "from a feeling of sympathy in consequence of her sex, and pregnant condition, and the fact that she was once a slave," nor could they acquit "from a feeling of prejudice against slaveholders." The jurors deliberated for just ten minutes before returning with the verdict that Gaines was not guilty by reason of insanity.

Following the verdict, federal officials sentenced Gaines to an unspecified amount of time in the Government Hospital for the Insane (renamed St. Elizabeth's), where she stayed in newly built facilities for the "colored insane." Hospital officials diagnosed Gaines with "mania hysterical." They believed her mental condition stabilized in October, with the birth of her son, and in February they invited her father to come retrieve her. Having stayed almost nine months, Gaines was released on April 16, 1870. She presumably returned to Virginia, carrying with her the infant son she had named Daniel Webster Gaines.

Sadly, Minnie's son ended up in an orphanage in Boston, Massachusetts sometime in 1880 when he was 12 years old. He lived the rest of his life in the Boston area working as a waiter in restaurants; he later married, had kids, but tragically died young of tuberculosis in 1913.

Sources: "Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C." By Kate Masur

--/--/----

Separate But Equal

A partition separates white and black patrons at a movie theater in Washington DC.

History of Segregation in America

After the Civil War, millions of formerly enslaved African Americans hoped to join the larger society as full and equal citizens. Although some white Americans welcomed them, others used people’s ignorance, racism, and self-interest to sustain and spread racial divisions. By 1900, new laws and old customs in the North and the South had created a segregated society that condemned Americans of color to second-class citizenship.

Sources: Arthur Fellig (Weegee) Photographer, Weegee Collection

--/--/----

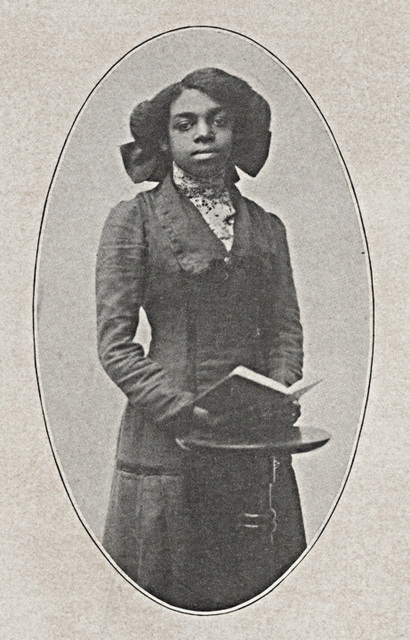

Christina Moody

In 1910 at the age of sixteen she published a book of poems titled, 'Tiny Spark' and also wrote a book that same year on the East St. Louis Riots. At least one of the books was published by a black family owned publishing company in Washington DC., Murray Brothers Printing Company (Washington, D.C.), Publisher Murray Brothers Press, 1910

I've been trying to find out more about this young woman ... what I've come up with so far is that I believe she was born somewhere in North Carolina and her family eventually relocated to the District of Columbia. To my knowledge she was the author of two books of poetry, the above referenced book of poems and 'The Story of the East St. Louis Riot' (1917). At some point she eventually taught home economics at and was the school secretary at Deanwood School in Washington, DC.

She married Robert Briggs on December 18, 1912. He died just seven years after their marriage. The couple had one child, a son Robert Briggs, MD. He practiced medicine and resided in Indianapolis, Indiana. He married Virginia Ross Briggs. He died at the age of 74 in 1990.

You can read A Tiny Spark (free):

archive.org/details/tinyspark00mood/mode/2up

--/--/----

Servants of the White House

Standing: Jane Humphreys, Henry Harris, Beverly Lemas, Mary Monroe, Edgar R. Beckley, Telemachus Ford. Seated: Maria Rustin, Mary Waters, Winnie Monroe.

This image, taken in May 1877, is believed to be the first photograph ever taken of White House staff during Rutherford B. Hayes Administration (1877-1881). Henry Harris and Beverly Lemas were employed as waiters. Harris joined the staff in 1871 and Lemas in 1872. Edgar R. Beckley had been employed as a messenger at the White House since April 1869. Telemachus Ford and Jane Humphreys became part of the White House staff during the first weeks of the Hayes administration. Winnie Monroe, whose mother had been freed from slavery by Lucy Hayes' parents, served as the children's nurse and the family's cook during Hayes' years as governor. Winnie and her daughter Mary accompanied the Hayeses to Washington. When Hayes left office in 1881, Winnie returned with the family to Spiegel Grove. However, after the excitement of life in Washington, she soon grew bored. Within a matter of months, Winnie was on her way back to Washington where she lived until her death in 1886. Other staff members, not pictured, included T. F. Pendel, chief doorkeeper; and Charles Loeffler, the chief usher; and Billy Crump, White House steward. Crump served with Hayes in the Civil War. Isaiah Lancaster, the president's valet, had been with Hayes during his governorship.

Rutherford B. Hayes

Presidential Center

--/--/----

Emma Merritt

Emma Frances Grayson Merritt was born on January 11, 1860, in Dumfries, Virginia, one of seven children, the third of four daughters of John and Sophia (Cook) Merritt. When she was three years of age, her parents moved to Washington, D.C.

Merritt was a teacher well before she received any higher education. She taught first grade in the public schools of the District of Columbia beginning in 1875, when she was 15. She continued to teach while completing the normal school program (1883-87) at Howard University. In 1897 she was appointed an elementary school principal. She continued intermittent study of the social sciences at Columbia (later named George Washington) University until the end of the century.

Merritt established the very first kindergarten in the United States for black children in 1897. She became director of primary instruction in the District of Columbia in 1898 and a supervising principal in 1927, remaining in that role until her retirement in 1930.

At historically black universities and colleges throughout the country, Merritt was a prized lecturer in the education of young children. She was an organizer and director of the Teachers' Benefit and Annuity Association in the District of Columbia and president of the capital branch of the NAACP, among many civic responsibilities.

She died on June 8, 1933, in Washington DC.

The location of the Emma F.G. Merritt Public School is on the site of the former Suburban Gardens Amusement Park in a building constructed in 1943. According to oral history given by former teachers, while the site has changed, the philosophy of self reliance has essentially remained the same. Now called Merritt Educational Center, the school is located at 5002 Hayes Street, NE., Washington D.C.,

Sources: Deanwood, A Model of Self-Sufficiency in Far Northeast Washington, DC, Deanwood History Project; Biographical Dictionary of Modern American Educators, by Frederik Ohles, Shirley M. Ohles, and John G. Ramsay; The Voice, vol. 1, 1904

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest items - Subscribe to the latest items added to this album

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

X