South-East Asian scripts of Indian origin

The roots of Sanskrit's charm

Delaware Water Gap

Nahuatl lyric

Hush Puppies

Tree of Life

Minihaha fall

Witing on the table

Capitol

Capitol

The Haven

View From Guthrie Theater tower

View From Guthrie Theater tower

View From Guthrie Theater tower

Stream

I am not a person

Misgivings

Sociobiology

View From Guthrie Theater tower

Egg currey

Farmers Market

Farmers Market

Farmers Market

Gladious

Photographer

Snow White's visit

Size of a carbon atom

Minneapolis

Minneapolis

Hammered Dulcimer (Santoor)

Minihaha Falls

Ukulele player

"Ludul Bel Nemeqi" - I will praise the Lord of Wis…

An Artist

Mall of America

Mall of America

Mall of America

Mall of America

How English has changed over the last 1000 years

Tulip

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

- Photo replaced on 06 Oct 2013

-

384 visits

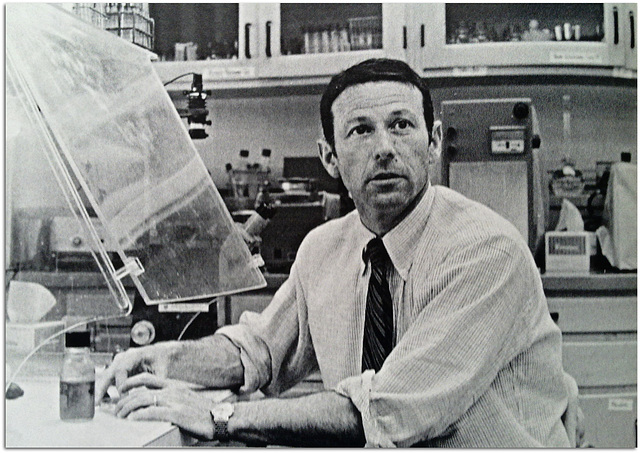

Paul Berg

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Knowing grants one form of control. The ancient Roman poet Lucetius believed that the idea of the conservation of matter – that matter could not be created or destroyed – would free humankind from the capricious interference of the gods. There are more active forms of control. In Sumatra, women who sow rice let their hair hang long down their backs, so that the rice will have long stalks and grow well. The ancient Egyptians crossbred horses, cattle, wheat, and grapes, to produce animals and food of higher quality. The early Romans built massive stone aqueducts to convey water from one place to another.

Of all aspects of nature, the phenomenon of life is the most complex. And the control of life, perhaps, satisfied most deeply our desire for control over our physical world. indeed, one can view the subject of biology through the centuries as a deepening understanding of the mechanisms and controls within living substance. Just in the twentieth century, following the chapters of this book, one might point to the discovery of hormones, which comprise a chemical command and control system; the discovery of neurotransmitters, the mechanism by which nerves communicate with each other; the discovery of penicillin, the first antibiotic, which gave human beings much more control over infectious disease; the discover of structure of DNA and the mechanism by which genetic information is encoded in each living cell; and the discovery of the design of the hemoglobin molecule and the mechanism by which oxygen, and most vital of all gases, is held and released in the body.

In the long list of endeavors to control living substance, the ability to reprogram DNA, to alter the instructions of life within each living cell, is the most profound. Now, we have become architects of life. By splicing genes together, we have created living organisms that never existed before. We have redesigned the lowly bacterium E. coli so that it produces insulin for ailing diabetics. We have altered the DNA of maize and soybeans to make them resistant to insects and disease. In a flight of fancy, we might even imagine re-creating ourselves – as in M.C.Escher’s eerie picture of a hand drawing itself. In which case, we could be the first substance in the universe to design itself. Such power, perhaps the ultimate power, raises more ethical, philosophical, and theological questions than any previous development in science.

The history of gene splicing, also called recombinant DNA or genetic engineering, is recent. It began with a paper by biochemist Paul Berg of Stanford University and his collaborators in 1972. in his goal to insert new genes into living cells, Berg was the first scientist to splice together segments of DNA from different organisms. He was forty six years old at the time. soon, Berg became aware that he had set into motion a new biology of unimaginable consequences. Eight years later, on the occasion of his Nobel address, he thanked his students and colleagues for sharing with him “the elation and disappointment of venturing into the unknown” ~ Pages 482 / 483

Sign-in to write a comment.